6

Feb

The Geopolitics of the Nile and the Red Sea: What is Behind Ethiopia’s “Two Waters” Doctrine?

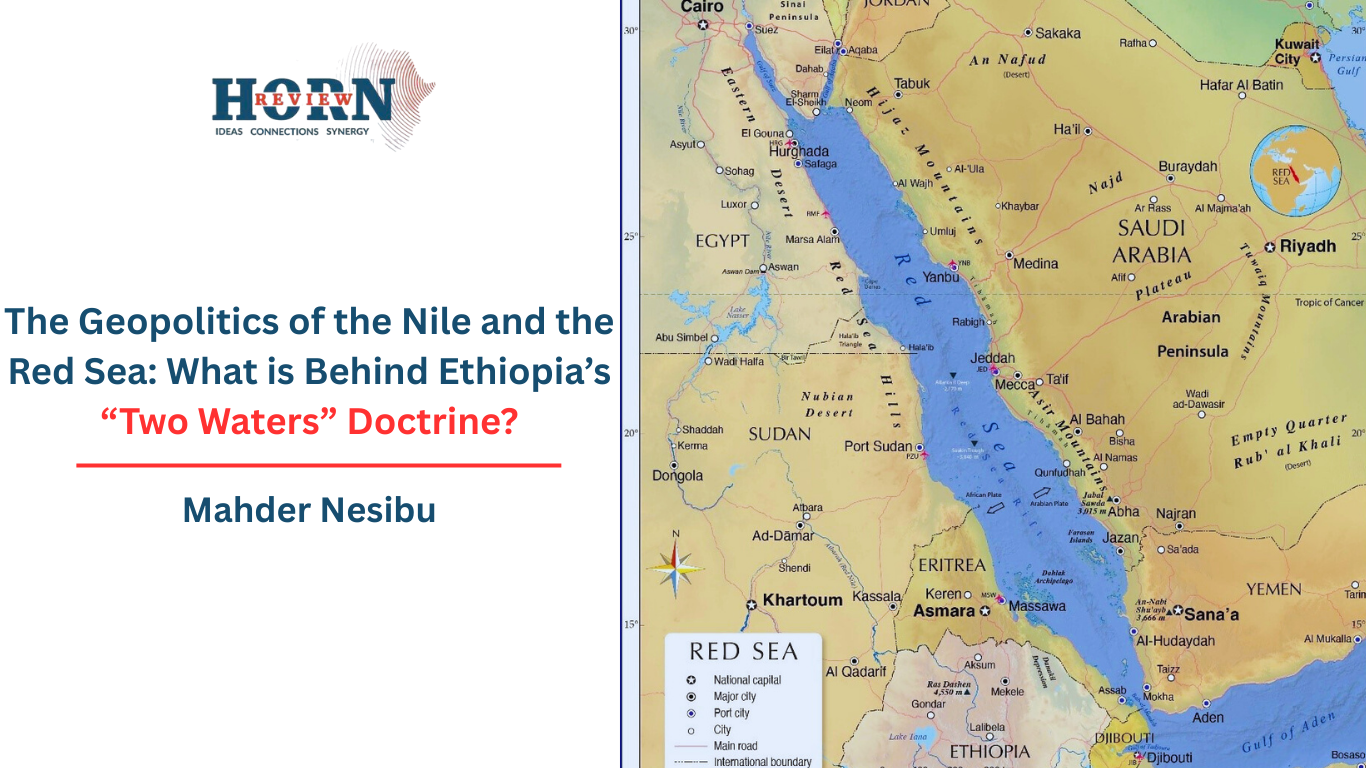

At the opening session of Parliament last year, Ethiopia’s President, Taye Atske Selassie, told lawmakers and senior leadership that “Ethiopia exists between the Nile and the Red Sea and its destiny is tied closely to these two waters.” He further stated that Ethiopia operates within an international system that is “in flux.” His remarks offer a concise entry point into the current leadership’s rationale for prioritising both the utilisation of the Nile and the pursuit of access to the Red Sea, and for viewing the two bodies of water as a single, interconnected geopolitical question rather than as separate strategic issues.

The emerging narrative of the “two waters” reflects a broader shift within Ethiopia’s political leadership and intellectual circles toward a more explicitly geopolitical worldview, one that seeks to regionalise Ethiopia’s national security and developmental interests. This conceptualisation of Ethiopia’s regional environment appears increasingly articulated at the highest levels of the state. It is, fundamentally, a view of the geopolitical. While the Nile and the Red Sea are ultimately pursued to meet Ethiopia’s developmental aspirations, the framework through which they are approached contains a pronounced realpolitik element.

Within this worldview, Ethiopia’s leaders increasingly weave together history, hydro-politics, regional security dynamics, and perceptions of an evolving international system. The Nile and the Red Sea are treated as the principal arenas in which Ethiopia’s position must be secured. Anchoring the country in these two strategic spaces is understood as essential to guaranteeing national security and establishing a regional balance of power in which Ethiopia can operate with strength and autonomy. The interlinking of the two waters appears as an attempt to reconstitute autonomy within a regional order historically experienced as constraining, at a moment when global norms are perceived to be losing traction.

A key pillar of this interpretation lies in the historical lens through which Ethiopia increasingly views its regional position. The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), which came to fruition only last year, is the product of decades-long efforts to utilise the Blue Nile and of a much longer historical dynamic that has defined Ethiopia’s immediate environment for centuries. The hydro-politics of the two waters is understood as deeply historical. When the President spoke of Ethiopia as sitting between the Nile and the Red Sea, he advances a historical claim as much as a geographical one. His reference to an “unjust side-lining” situates the doctrine as an effort aimed at undoing perceived historical injustices.

The Nile has been the defining feature of the geopolitics of Northeast Africa in modern history. Its centrality to Egypt’s national identity has, in parallel, shaped Cairo’s foreign policy across the region. This geopolitical reading of the Nile as a strategic natural resource led Egypt to adopt a zero-sum approach in which ensuring the uninterrupted flow of Nile waters required either control over its sources or the extension of Egyptian influence across upstream states. This logic inevitably brought Egypt into conflict with the Ethiopian state, a pattern that has persisted in various forms over time.

Egypt’s strategic challenge, however, was that the Blue Nile, the source of much of the Nile proper, lay under the sovereignty of an Ethiopian state which possessed a “disciplined administration and army”. For Ethiopian leaderships and intellectuals, the tension between Egypt’s ambition to subordinate the entire Nile system and the resistance it encountered from a complex Ethiopian polity is central to understanding the region’s geopolitics. Within this interpretation, historical challenges to Ethiopia’s sovereignty over modern-day Eritrea are viewed as extensions of Nile hydro-politics rather than as isolated territorial disputes.

This reading rests on the understanding that Eritrea’s complicated historical trajectory, and its gradual detachment from the Ethiopian polity, began with Egypt’s entry into the territory in the nineteenth century. While Cairo’s motivations may have been multifaceted, the primary rationale is interpreted as the creation of a strategic front from which to challenge the Ethiopian state and weaken its capacity to assert control over Nile waters. From this perspective, Egypt’s enduring involvement in Eritrea is understood as part of a broader effort to constrain Ethiopia along multiple axes.

Ethiopia’s loss of access to the sea is therefore interpreted in Addis Ababa as the outcome of a wider strategy aimed at preventing the country from developing the leverage necessary to assert its rights over the Blue Nile. Egyptian pressure is taken as having operated simultaneously on two fronts: through direct confrontations along Ethiopia’s western periphery, and through northern entry points such as Massawa, which opened an additional axis of strategic pressure.

Against this historical backdrop, Ethiopia’s contemporary leadership has increasingly articulated the Red Sea as central to the country’s strength and regional standing. In 2022, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed told senior leadership that Ethiopia’s power and position in the region are tied directly to the Red Sea. This articulation forms part of a broader effort to undo the regional order established by the hydro-politics of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The success of the GERD is viewed as a milestone in overcoming long-standing constraints imposed on Ethiopia over the Nile, and this “undoing” of the Nile order is now feeding into a parallel rationale regarding the Red Sea.

The Prime Minister has framed this logic explicitly, describing Ethiopia as “an island surrounded by water but deprived from it.” Several points emerge from this articulation. First, while all Red Sea littoral states hold stakes in the Nile Basin and benefit from waters originating in the Ethiopian Highlands, Ethiopia itself is excluded from the Red Sea system. Neighbouring states are able to integrate their geopolitical calculations across both water systems, while Ethiopia remains locked out. This asymmetry is presented as evidence of a harsh regional order, captured in the Prime Minister’s observation that Ethiopia “provides its neighbours with fresh water yet is locked out of the Red Sea.”

Second, he has addressed what he described as a long-standing “taboo” surrounding Ethiopia’s interest in reclaiming a presence on the Red Sea, noting that a similar taboo once surrounded Ethiopia’s efforts to utilise the Nile. In both cases, Ethiopian initiatives were framed externally as destabilising despite being rooted in development and sovereignty concerns.

There are variations in how securing access to the sea could be arranged, and Ethiopia has advanced different proposals regarding potential modalities. More specifically, however, there appears to be a triangulation around the port of Assab as the most viable option. This preference is often explained in logistical terms, yet those logistical considerations are themselves rooted in history. In Ethiopia’s most recent past, Assab served as the primary port for the country’s maritime activities, and the road networks, supply chains, and commercial arrangements that support this assessment were built around that role. The logistical case for Assab derives from its historical use.

Beyond Assab, the rationale extends further. The pursuit of Red Sea access is framed as part of a broader effort to undo Ethiopia’s side-lining from the maritime domain altogether. It rests on the assumption, frequently articulated by the Prime Minister, that the Ethiopian polity has historically been at its strongest when it possessed a meaningful presence on the Red Sea.

The primary rationale underpinning this pursuit, much like the GERD project, is framed in developmental and economic terms. Ethiopia’s population continues to grow rapidly, while its productive capacity and demand for access to global markets expand in parallel. The country remains dependent on increasingly costly and congested port access arrangements. In practical terms, the centrality of the Red Sea is therefore self-evident.

Yet Ethiopia’s leadership has consistently emphasised that economic logic alone does not fully capture the stakes involved. Dependence on access entirely controlled by another state, within a region characterised by limited integration and political volatility, is viewed as a structural vulnerability. In geopolitical terms, coupling authority over the Blue Nile with a presence on the Red Sea is understood as the basis for establishing a regional balance of power with Egypt. Cairo’s unilateral utilisation of Nile waters, combined with its control over the Suez Canal and its expanding influence across the Red Sea, has long formed the pillars of its regional status. For Ethiopia, meeting Egypt from a position of strength requires the creation of a regional equilibrium capable of safeguarding national security.

The President’s observation that Ethiopia operates within a world “in flux” signals a perceived erosion of the post–Cold War worldview that previously shaped Ethiopian foreign policy. The “rules-based order” did fail to deliver, and it is itself in decline and under significant strain. Ethiopia’s earlier acceptance of this system led it to strip the geopolitical significance from the Red Sea, treating access to ports as a purely commercial matter and viewing them as assets to be acquired through market transactions.

This framing is now visibly rejected by the current administration, which regards dependence on access as an inherent vulnerability. At the same time, the weakening of the multilateral system requires states to anticipate what the emerging order may look like and how they will adapt to it. For Ethiopia, this environment is understood as unpredictable, reinforcing the perceived need for a foreign policy grounded in geopolitical calculation rather than normative expectation.

By Mahder Nesibu, Researcher, Horn Review