16

Dec

Isaias’s Bet on a New Regional Axis and the Fault Lines Driving His Diplomacy

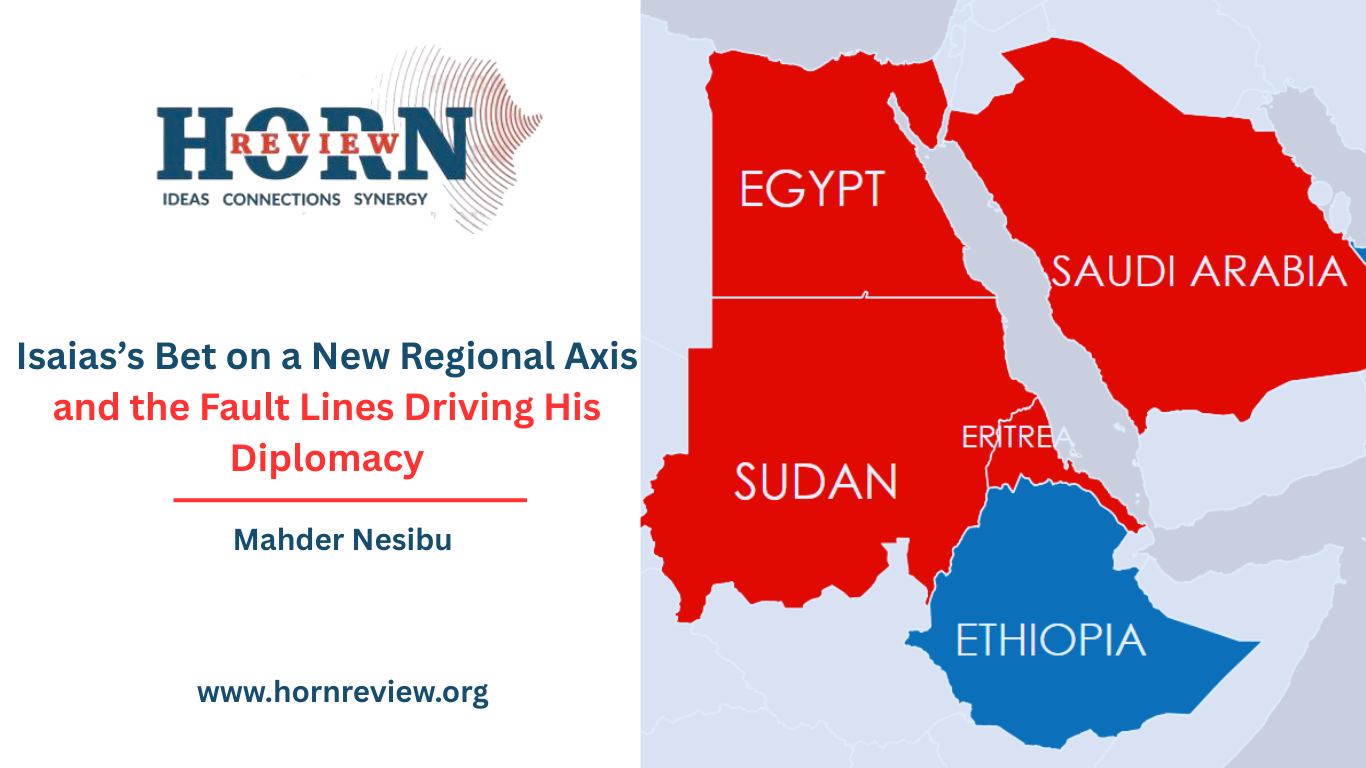

President Isaias Afewerki’s recent regional tour, which took him to Egypt, Sudan, and Saudi Arabia within a short two-month window, unfolded under the cover of formal diplomatic language. Statements from Eritrea’s Ministry of Information spoke of mutual concerns, regional security, and economic cooperation. Yet the timing and sequence of the visits reveal a more consequential story than official communiqués imply. The Horn of Africa and the wider neighbourhood are entering a period of fluid geopolitical reconfiguration, and Eritrea’s leadership sees in this transition both an existential threat and an opening. Isaias’s movements offer insight into how he imagines the current regional landscape and how he believes Eritrea might navigate it.

Tensions between Eritrea and Ethiopia are at their most severe in years. Political actors across the region, as well as international observers, openly speculate about the possibility of armed confrontation. The anxiety is visible in diplomatic conversations, intelligence assessments, and the behaviour of armed groups inside Ethiopia. This atmosphere forms the backdrop to Isaias’s diplomatic engagements. The visits expressions of a geopolitical reading that places Eritrea at the centre of multiple, overlapping rivalries.

Eritrea’s most immediate concern is Ethiopia. Over the past year, Asmara pursued a strategy rooted in infiltration of Ethiopia’s internal security landscape. Eritrea sought to construct influence networks, mobilize proxies, and support armed actors who could pressure the federal government from within. Yet these proxies are now showing signs of decline. The Fano rebellion, which presented a sustained armed challenge to the federal government in the Amhara region, is fracturing. Some factions have begun negotiating with the regional administration, withdrawing from active confrontation. The TPLF, despite its long-standing capacity for organization, is weakened by internal divisions, splinter armed elements in Tigray, and persistent disputes between its political leadership and its remaining military wing. These developments undermine Eritrea’s ability to rely on proxies as a strategic tool.

Recognizing this, Asmara appears to be extending its approach to a broader regional axis rather than depending solely on internal Ethiopian vulnerabilities. Sudan lies at the centre of this recalibrated strategy. The ongoing civil war there is one of the most complex geopolitical theatres in the region, drawing in neighbouring states and external powers whose competing interests intersect at Sudan’s fault lines. For Eritrea, Sudan offers the opportunity to embed itself within this wider competition and turn it into leverage.

Asmara’s involvement in Sudan is neither new nor marginal. Eritrea has long cultivated influence across communities and armed groups along the shared border. Rebel factions connected to the Beja Congress, historically mobilized against previous Sudanese governments, have been shaped and directed from Asmara. These networks have been used by Eritrea to pursue its regional objectives, and in the context of the current conflict, their value has grown. The recent diplomatic exchanges make this clear. Isaias’s visit to Port Sudan last month followed an earlier high-profile visit by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan to Asmara, and it preceded additional delegations from the Port Sudan authorities, including Prime Minister Kamil Idris and Burhan’s deputy, Malik Agar. Their public expressions of gratitude reflect Eritrea’s growing utility to the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF).

Sudan’s need for military resources has deepened its dependence on Eritrea. Reports indicate that Eritrea has provided training, weapons, and logistical support to forces allied with the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF). Eritrea’s territory is also understood to have become a transit route for weapons destined for SAF. For Burhan, this support fills crucial gaps; for Isaias, it opens access to a geopolitical arena whose repercussions stretch from the Red Sea to the Nile Basin.

The Nile dispute is perhaps the most significant of these arenas. Egypt’s frustration with its inability to secure an agreement favourable to its interests has escalated into repeated confrontations with Addis Ababa. Cairo’s rhetoric has grown sharper, its diplomatic engagement more forceful, and its geopolitical posture more escalatory. Egypt is now cultivating influence across Ethiopia’s neighbourhood, strengthening its presence in Somalia, Djibouti, and critically, Eritrea. As Ethiopia consolidates its aspiration to secure access to the Red Sea, Egypt sees an opportunity. From Cairo’s vantage point, Eritrea is a potential pressure point, a neighbour whose antagonism towards Ethiopia can be aligned with Egyptian interests.

This explains the strategic undertone of Isaias’s visit to Cairo. The trip allowed Asmara to exploit Egypt’s frustration and feed into a broader contest of influence in the Horn. Ethiopia’s maritime aspirations, vilified and framed by Eritrea as an externally driven ambition, only intensified Cairo’s interest in cultivating Eritrea as a partner. For Eritrea, the alignment with Egypt situates it within one of the region’s most consequential geopolitical fault lines, giving it visibility and perceived leverage.

Yet it is the involvement of the Gulf powers, particularly the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, that completes the picture. The UAE has become the most active external actor in the Horn and Red Sea region, extending its influence through ports, security partnerships, and indirect military or political intervention. Its role in Sudan is the most controversial. Widespread allegations link Abu Dhabi to sustained support for the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), whose recent territorial gains have been accompanied by reports of atrocities. The international criticism surrounding the RSF has created a reputational problem for the UAE, and Eritrea has seized the opportunity.

Asmara’s propaganda apparatus has framed the UAE as the principal destabilizing power in the region. Eritrean messaging now routinely depicts Ethiopia’s maritime strategy as a project engineered by Abu Dhabi. The President himself has embraced this narrative, positioning Eritrea as a guardian against foreign manipulation. This portrayal is meant to influence regional perceptions, delegitimize Ethiopia’s policy agenda, and draw sympathetic actors closer to Asmara.

This strategy intersects with a second layer of calculation: the friction within the Gulf itself. Although the monarchies often appear coordinated, their foreign policy agendas diverge in significant ways. The UAE and Saudi Arabia differ in how they approach the Middle East and the Horn of Africa. In Sudan, this divergence is visible. Saudi Arabia has retreated from its earlier support for SAF and is now focused on mediation, working closely with the United States. The UAE, by contrast, maintains an assertive posture, continues to deny direct involvement while weapon flows to the RSF reportedly persist, and the group achieves battlefield gains. This contrast has opened space for Eritrea to present itself as a useful partner to Riyadh.

Developments in Yemen further strain the relationship between Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Reports suggest that UAE-backed elements within the internationally recognized government have launched a new offensive in the south, with the Southern Transitional Council (STC) acting with Emirati approval. This move directly undermines Saudi Arabia’s efforts to stabilize Yemen through negotiations that include the Houthis. Such events feed into Asmara’s broader narrative: that the UAE seeks dominance across the Red Sea region, that its interventions disregard local stability, and that Eritrea sits on the opposing side of this regional imbalance.

Isaias imagines that by aligning with Riyadh’s frustrations over Abu Dhabi’s regional behaviour, and by inserting Eritrea into the Sudan conflict and the Nile dispute, he can expand Eritrea’s relevance. The attempt is to turn Ethiopia’s tensions with Eritrea, the Egypt–Ethiopia rivalry, and the criticisms directed at the UAE into a composite geopolitical field where Eritrea can manoeuvre. The hope is that this broader alignment will compensate for Eritrea’s material weakness and offer it a buffer in a future confrontation with Ethiopia.

Yet the scheme carries evident miscalculations. Eritrea is the least capable actor within the network of states and forces it seeks to influence. Its ability to shape decisions in Port Sudan is entirely contingent on wartime needs. Egypt’s engagement with Eritrea is tactical; Cairo sees Eritrea as one among several instruments to pressure Ethiopia, not as a strategic partner. Saudi Arabia, while cautious about Emirati overreach, is not likely to extend Eritrea the degree of political or military support that Asmara imagines. The narrative that Ethiopia’s pursuit of sea access is an externally imposed agenda misunderstands the internal popular resonance of the issue within Ethiopia.

Vision 2030, which lies at the core of Saudi Arabia’s contemporary foreign policy, places structural limits on Asmara’s ability to draw Riyadh into axis politics. The Kingdom’s emphasis on de-escalation, diplomacy, and mediated engagement has translated into a cautious approach to the Horn of Africa, one that prioritizes the containment of instability and the expansion of economic presence over hard alignment. While Emirati engagement with Ethiopia may appear more visible, and Riyadh’s diplomatic outreach to Asmara can be read as a counterweight to Abu Dhabi’s influence, Saudi Arabia’s material interests in Ethiopia are both deeper and more consequential. Framed by Ethiopia as an “advanced strategic relationship,” Ethiopia fits squarely within the Kingdom’s broader agenda of economic diversification. Saudi investment across Ethiopia’s economy is extensive, and bilateral trade flows remain substantial. In this context, Isaias’s calculus underestimates Ethiopia’s importance to Saudi Arabia and misreads the economic logic shaping Riyadh’s regional diplomacy.

The broader regional environment is marked by constant shifts. New alliances emerge as quickly as they dissolve. Sudan’s war has created volatile middle-power arrangements that transform the political landscape with little warning. Eritrea is attempting to navigate these currents, but its capacity is limited, and the risks of overextension are high. While its involvement in Sudan offers it temporary visibility, the structural constraints shaping the region’s geopolitics remain largely beyond its control.

For Ethiopia, these dynamics carry direct implications. Addis Ababa’s policy of neutrality towards the Sudan conflict, grounded in the desire to avoid entanglement, may carry unintended costs. As Port Sudan cultivates its own alignments and Eritrea manoeuvres to position itself as indispensable to the SAF, Ethiopian interests risk being overshadowed or misrepresented. Eritrea’s framing, if left uncontested, can shape perceptions in ways that complicate Ethiopia’s diplomatic posture.

By Mahder Nesibu, Researcher, Horn Review