Why is a large dam important for Ethiopia? Experiences from the Danube River

Why is a large dam important for Ethiopia? Experiences from the Danube River

Silabat Manaye

Silabat Manaye is an international relations professional based in Addis Ababa. He obtained his Bachelor of Science in Geography and Environmental Studies from Wolayta Sodo University and his Bachelor in Science from New Generation University College in Addis Ababa. Silabat also completed his Master of Arts in Diplomacy and International Relations from the Ethiopian Civil Service University. His research interests include water politics, Peace journalism, as well as Digital and mobile journalism

In the case of Ethiopia, about 90% of the available water is received mainly in three months. Hence, dams could effectively store water during heavy rain seasons between June to September and some extent during the short rainy seasons.

Large water storages are therefore essential. In addition, we can expect the following advantages could be expected from building big dams in the Blue Nile basin: The flood waters are wasted unless large major dams are constructed, Large dams are eminently suited for carrying over storage and thus impart greater reliability and stability to the system, Large dams generate cheap and clean hydropower, Dams provide the most effective way of flood regulation and control.

Large dams are most reliable during drought periods as small storages are fast depleted and suffer excessive evaporation. In drought years, small dams are scarcely reliable. Longevity as large silt pockets, per unit areas stored with large dams, is much less as compared to small dams.

Diversion and transfer of surplus water to water-scarce basins can be an option only through big dams. Employment potential is higher in large dams throughout the year. In the case of small dams, there is little employment potential as seasonal rains affect only small local areas.

The imperatives for large water storage were supported by the former President of the World Water Forum Council who stated that “some 8,000,000 dams (of which 45 000 are major, higher than 15 meters in height) exist around the world delivering energy, flood protection and water for household, industrial and agricultural use”

He further stated that “despite the drawbacks, the world’s growing population and their need for greater economic development call for more water, in which demand will exceed availability. More and larger storage will be necessary to meet the challenges of development and socio-cultural fabric and make sure that those people affected by the development of dams will be better off than the alternative.

While giving special attention to the environmental and displacement aspects, Ethiopia should construct large-scale dams that: increase economic and social productivity and hence increase consumption of goods and services, irrigate 2.2 million hectares identified in the basin, distribute benefits to millions of inhabitants through employment in mechanized agriculture in the basin, provide better settlement, equipped with socially, economically and technically sound services in the basin for millions and change their life; producing complex hydroelectric power for trade with the trans-boundary countries.

Therefore, Ethiopia needs urgent action on matters concerning the building of major dam structures in the Abbay, Baro-Akobo, and Tekezze catchments and other River basin areas in accordance with some detailed studies and engineering designs.

Ethiopia has made many valuable studies and design works without much chance of putting them into action mainly because of lack of funds. To date, Ethiopia is the most minor user of the Blue Nile run-off in the Eastern Nile Basin, compared to Sudan and Egypt. At the national level, economic and institutional capacities are also limited. Despite many hindrances, Ethiopia should concentrate on the modern agricultural development options, focused on the rivers so that these resources could be utilized to realize meaningful irrigation programs.

Climate Change should concern the Nile Nations

A holistic approach to conservation, protection and utilization of the Nile River basin was sparsely implemented. The long-standing dispute over the Nile River was primarily on the utilization of the waters. But without arriving at a comprehensive governance scheme to address the environmental problems posed against the basin an equitable and reasonable share of the Nile waters would not be secured.

The blame must go to the downstream countries for their reluctant approach to a basin-wide agreement to address the governance challenges including the climate change impacts. Benefit-sharing should come after sharing of burdens on the costs of conservation and protection of the Nile environment.

Climate change has become a global threat to the environment including watercourses. The globe has launched several international mechanisms to deal with climate change.

The 2015 Paris climate accord was the latest of all initiatives. There is a nationally determined emission reduction to withhold the global warming rate below 2 Degree Celsius. The Nile riparian states are duty-bound to mitigate the environmental problems threatening the water flows of the Nile River.

Their mitigation should be expressed through their cooperation in afforestation programs on the headwaters and tributaries of the Nile River. Those headwaters are located in Ethiopian highlands. Ethiopia has embarked on the planting mission of twenty billion trees within a four-year period.

The downstream countries should participate in this green legacy mission and should cover the conservation and protection costs of the Nile basin. To that end, Ethiopia should offer a call for participation in the green legacy mission to the downstream nations.

For the downstream nations, participating in the greening of Ethiopian highlands would be a mitigation strategy for the millennial damages caused to the Nile River. They have depleted the Nile surrounding area with over-exploitation and mismanagement of the river. With that said, long-term cooperation on the conservation and protection of the Nile River Basin should be governed through basin-wide legal and institutional frameworks. Such a basin-wide arrangement could establish a permanent river basin commission to administer and facilitate cooperation among the riparian nations in the fight against climate change and its adverse impacts on the Nile ecosystem.

Lessons on Governance for Nile Nations from the Danube River

The Danube River Basin Cooperation provides a laudible lesson and example to the nations of the Nile Basin, as there are striking similarities between the two basins. The anticipated lesson to be learned by the Nile Nations from the Danube River Basin Cooperation is the harmonization and integrated management that brought tangible results and ensured peaceful co-existence within that region. Some of the outstanding achievements of integrative development and management approach of the communities of the Danube River Basin and their experiences are summarized below to illustrate the power of harmony and spirit of the shared responsibilities of the ordinary inhabitants of large river basins to the Nile families.

As mentioned in the study made by Oregan, Sullivan, and Bromley, the Danube is a large river that covers approximately 800,000 square kilometers in the territories of 18 states, with over 80 million inhabitants and 60 large and growing urban centers. The Danube is a slow-moving river with well-developed alluvial plains in its course. The Danube River covers an area of 675,000 ha and is internationally recognized as one of the most important watersheds in Europe.

The basin area covers all of Hungary, most of Austria, Romania, Slovakia, Serbia, and Montenegro; significant parts of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech and Moldovan republics, as well as a smaller area of Germany and Ukraine. Albania, Italy, Macedonia, Poland, and Switzerland also have small geographical areas within the basin. The Danube River Basin is spread across countries with very different levels of economic development and social and environmental diversities. Germany and Austria, highly developed nations, are located in the upper basin with longstanding membership of the European Union. In the middle basin Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungarian, and Ethiopia are experiencing an appreciable degree of economic growth. Further downstream Romania, Bulgaria, and Ukraine are less developed states in Europe but they are experiencing political and economic transition. Also, within the basin are the Former Yugoslav republics and northeast Moldova, the least developed country in Europe, heavily dependent on agriculture.

Institutional Framework Experience

The development of the Danube River Basin is coordinated through several institutions formed by all member states and policies directed by these bodies. The most important of the European-level policies is the European Water Framework Directive (WFD), which seeks to introduce comprehensive river basin management and environmental protection initiatives across Europe. The Danube River Protection Convention forms the overall legal instrument for cooperation on transboundary water management in the Danube River Basin. The Convention was signed on June 29, 1994, in Sofia (Bulgaria) and came into force in 1998. Based on this document, the International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River (ICPDR), with 13 cooperating states and the European Union, was established in practice. The ICPDR makes recommendations for improving water quality, developing mechanisms for flood and industrial accident control, agreeing on standards for emissions, and ensuring that these measures are reflected in the cooperating states’ national legislations and applied in their policies.

To meet the needs of this single basin-wide management plan, each country is in the process of preparing national reports (roof reports) which give an overview of WFD issues such as the pressures on the surface and groundwater resources and related environmental impacts that will form the basis of the river basin management plan. In the 1990s, countries of the DRB took significant steps to improve the management of the Danube with recognition of the growing regional and transboundary character of water management issues and related environmental issues. In 1991, the Environmental Program for the Danube River Basin (EPDRB) was established in Sofia, Bulgaria by the countries of the DRB, together with international institutions and NGOs, to start an initiative to support and enhance actions required for the restoration and protection of the basin. This was followed by the Convention on Cooperation for the Protection and Sustainable Use of the Danube River Basins signed in June 1994. It was signed by 11 states and the European Union and provided the legal basis for the protection and use of water resources in the basin.

Water Use Practices

The Danube plays an important role in the development of the region, as its communities rely on it for water supply (domestic, agricultural and industrial), power generation, navigation, waste disposal, and recreation. The Danube waters have also been intensively harnessed for hydroelectricity (particularly in Austria and Germany) and irrigation schemes for agricultural developments (especially in the middle and lower basins).

The need for water storage in the face of seasonal variations and to generate hydropower have led to dam building across the basin. Between 1950 and 1980,69 dams with a total volume exceeding 7.3-billion-meter cube were constructed on the Danube River. Groundwater resources represent as much as 30 percent of the total internal renewable water resources of some DRB countries. Aquifers are the main resources of drinking water while some have permeable aquifers, which are highly vulnerable to pollution from point and nonpoint resources. The extent of hydro-morphological changes for navigation environmental has had a major impact on natural floodplains and their ecosystems. In many places along the river floodplains, meanders have been cut off from the river system. However, as a result, 80 percent of the historical floodplain of the larger rivers of the basin has been lost over the last 150 years. The loss of this area has led to a reduction of flood retention capacity and floodplain habitat. Some of the remaining areas have either received protection status under different national or European legislation or international conventions, while other areas remain vulnerable.

Civil societies and Private Institutions Environmental Experiences

The Regional Environmental For Central and Eastern Europe (REC), and the Danube Environmental Forum (DEF) represent nearly 200 NGOs across the region. The aim is to protect the Danube River and its tributaries, their biodiversity, and resources, through enhancing cooperation among governments, non-governmental organizations, local people, and all kinds of stakeholders towards sustainable use of natural ecosystems. Many of these institutions are participants in the annual Danube Day festivities marking the signing of the Danube Convention and celebrating the river, its ecology, and its people. Festive events, festivals, public meetings, and educational events take place along the river and Danube Day is described as a powerful tool for enhancing the “Danubian identity of people living in the basin, demonstrating that despite their different cultures and histories they have a shared responsibility to protect their precious resource.”

There is also increasing involvement from the private sector. At the basin level, the most visible private company involved in water resources management is the multinational Coca-Cola. Cola protects the Danube River Water Basin and it is committed to business approaches that preserve the environment and integrate principles of environmental stewardship and sustainable development into its business decisions and processes. At the local level, the company is piloting a number of water-themed sustainability projects, across the basin in partnership with local authorities and NGOs. Coca-Cola is also a major sponsor of Danube Day.

Share

Another Milestone in Ethiopia’s GERD project: a discussion with Professor Yacob Arsano.

Another Milestone in Ethiopia’s GERD project: a discussion with Professor Yacob Arsano.

Professor Yacob Arsano

Professor Yacob Arsano currently serves as an Associate Professor at Addis Ababa University’s School of Political Science and International Relations (AAU- PSIR). Dr. Yacob’s research focus on hydropolitics, coupled with his adamant advocacy for equitable water use in the Nile Basin, makes him a leading authority on inter-state relations in the Eastern Nile Basin.

His expertise, particularly on the construction of the GERD project and the consequent negotiations with riparian states, has allowed for a scientific framing of recently emerging water disputes in the region.

Question: What is the general guideline for utilizing a shared resource? Particularly as it relates to lower riparian countries?

Answer: According to the UN Convention on Nonnavigational Uses of International Water Courses, which was adopted in 1997, as well as the Cooperative Framework Agreement -CFA, which is an agreement that the Nile Basin countries signed in 2010, the use of shared waters should be reasonable and equitable between the riparian countries. It is accepted that if one country uses the shared waters, that country is required to be cautious not to inflict significant harm to other riparian countries. The three-round fillings of GERD in 2020, 2021, and 2022 have not caused any damage to Egypt and Sudan. There is no evidence for any presumed claims of harmful effects of the three GERD fillings.

This Declaration of Principles which was signed by the Presidents of Egypt and Sudan and the Prime Minister of Ethiopia in March 2015 is an excellent example of transboundary river development cooperation. In this agreement, many provisions indicate beneficial interests to all three parties. The understanding is that Ethiopia owns and manages the GERED and, upon completion “priority will be given to downstream countries to purchase power generated from GERD”., As you know, the filling process goes in tandem with the progress of the construction, in accordance with the Declaration of Principles. Thus far, I am yet to see anything that Ethiopia has done to undermine the agreement. So far, there is no evidence that the water going to Sudan and Egypt has been significantly reduced, blocked, or put in jeopardy.

It is open fact that Sudan suffers from cyclical annual Nile flooding in the months of summer., However, as a result of the commencement of the staged GERD filling destruction to life and property has been relatively minimal in downstream Sudan.

On the occasion of the completion of the third filling of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) Horn Review discussed with Professor Yacob Arsano the technical, cooperative, and policy issues surrounding the dam.

Question: The Egyptian Ministry of Foreign affairs has reported that Ethiopia wrote a letter to Egypt on August 2nd stating that it would be filling the dam in the months of August and September. However, Ethiopia completed filing the dam 15 days earlier, on July 18. What is your opinion on this matter?

Answer: As the owner of the dam, it is Ethiopia’s commitment to notify the lower Nile riparian states of its plans to fill the dam before doing so. Egypt’s accusation that “Ethiopia’s dam should not be filled” or complaints of receiving the letter after the dam has already been filled is simply a weak argument. The very purpose of building a dam is to fill it with water Ethiopia has the right to build the dam and fill it with water, without causing significant harm to downstream countries. So, Ethiopia is filling the dam parallel to the construction as agreed in the Declaration of Principles of March 2015. when the dam is fully completed, it will help avoid annual floods in the rainy season in downstream countries. Ethiopia should be thanked for this and many other benefits the GERD brings to Egypt and Sudan. I do not think Ethiopia should be accused by Egypt since this is the third filing, not the first. In my view, accusations from the Egyptian side are simply baseless.

Question: Professor, according to Asharq al-awsat news, this third filling, more than the previous ones, is expected to create more tension. Do you think there is some truth to that statement?

Answer: I do not think so. More than 80 percent of the construction of the dam has been completed since 2011, and the dam is now in its third round of filling. This is neither abrupt nor unexpected. Ethiopia didn’t flippantly start filling the dam., The dam was built for the sole purpose of filling it and producing electricity. When the first and second phases of filling took place, the countries on the lower river basin were made aware of the annual filling schedule. The third filling was executed in a similar manner.

Since the filling of the dam will not cause water depletion in Egypt or Sudan, they will not be affected by the filling of the third round. So, since there will be no water reduction expected, I don’t think this 3rd filling poses a problem; disagreement or controversy is unnecessary.

Question: Just to follow up on this question, to the best of your understanding, what are the significance and implications of Egypt’s claim of “historical rights?” Is there a precedent of historical rights over trans-boundary resources?

Answer: Because the agreements signed by Egypt with the British in 1929 and with the Sudanese in 1959, are not related to Ethiopia and other Nile riparian, Egypt and Sudan should not claim to be the sole proprietors of the Nile waters. The Nile is a shared resource by all riparian nations and is meant

to be utilized by all parties equitably and reasonably. It should, instead, be advocated for joint use of this precious resource amongst all parties.

Since it is the resource of the watershed countries, all parties involved are entitled to fair and equitable

usage. Therefore, it is unjustified for one or two parties to monopolize the shared resource. Ethiopia

and other upstream countries cannot be bound by the unilateral agreements of Egypt and Sudan between themselves or with an external actor in the Nile basin.

The international experience is that countries in respective river basins agree to utilize their shared resources jointly and collaboratively. They establish common principles and institutional mechanisms. For instance, the Mekong river basin riparian nations have established the Mekong River Basin Commission. Similarly, the riparian nations of the Senegal river basin have established Senegal River Basin Commission. Elsewhere in Europe, the Rhine and Danube riparian nations have respective river basin commissions for each of the shared rivers. Nowhere in the world, a single riparian country claims a monopoly of shared river waters. It is only in the Nile Valley, that the Egyptian party insists that the other riparian countries be governed by Egypt’s rules and interests.

Question: Until this third filing, downstream states were involved in tripartite negotiations. However, due to civil unrest in Sudan, the African Union also blocked the country from further participating. So, how will the negotiations continue in this situation? If there is any negotiation to happen, what kind of step will be taken next? Is it only with the two of them or how can this work for Egypt says that Sudan must enter?

Answer: Until April 2021, now, the Coalition Government of Sudan was attending the negotiation platform facilitated by the African Union together with Ethiopia and Egypt. But Egypt and Sudan are not willing to be on the negotiation stage putting up preconditions, and further stalling the negotiation process.

It is not the case that Egypt is not attending the negotiations because Sudan has been banned from the process due to the recent military takeover in Sudan. The actual fact is that together, Egypt and Sudan are making elaborate excuses for their refusal to proceed with the talks under the auspices of the Africa Union. Ethiopia has clearly explained that it does not accept the binding agreement which was initially proposed by Egypt after the failed Washington talks in January 2020. The so-called binding agreement which is very strongly put forward by Egypt and Sudan would be suicidal to Ethiopia’s sovereign rights over its national resources.

Question: Around 10% of the water reserve in Aswan High Dam is said to be reserved for Gulf states. Do you think this might be a complicating factor in potentially internationalizing the dispute?

Answer: I am not sure of the 10% figure. However, the water stored in the Aswan High Dam should, logically, be used by Egypt within the natural Nile basin. Egypt’s poor water management is self-evident, and this goes against the principles of protecting and conserving of the shared waters by each of the riparian countries. Egypt has unilaterally crossed a portion of the Nile waters to the Sinai Peninsula which is located outside the Nile watershed. Ethiopia has long protested this action. Second, it is known that Egypt created a new valley in the west direction of the High Aswan Dam to create a new valley. It is an open secret that Egypt has a new plan to divert the Nile waters to the New mega city on the western reach of the Suez Canal Ethiopia, along with other basin states continue to protest against the unilateral and wasteful utilization of the shared Nile water resources.

Question: While we are on the subject of informal objections or complaints, Egypt often runs to the UN security council with every possible objection. Entertaining this as a neutral objection, a neutral subject, and what is the merit and downfall of international level litigation?

Answer: So, if one country complains about another country’s actions as it relates to shared trans-boundary waters, that country is expected to follow the procedure of the International Court of Justice when the case is subject to international litigation. Similarly, bringing the case to UN Security Council should qualify the merit of security threats. However, barring other countries from using the trans-boundary water resources within respective territorial jurisdictions is a different ball game. Countries cannot go to ICJ or UNSC to protect their unlawful monopoly control of the otherwise shared waters. We are yet to see Egypt lodging a formal complaint to the concerned international tribunal because that course of action would not be in the best interest of either Egypt or Sudan. The previous two appeals of Egypt and Sudan to the UNSC did not induce the Council to consider the case as a matter

of security. The Council, however, advised the parties to take the case to the AU forum as an “African problem” and a development issue.

Question: We know that the dam is being built by internationally acclaimed construction companies. However, Egypt and Sudan claim to worry about the safety and structural integrity Dam. Is there any merit to this concern?

Answer: Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan jointly created an International Panel of Experts, IPoE, in 2012 and 2013 which included expert members from each respective country, in addition to intellectually recruited technical experts based on international competence. The International Panel of Experts then did evaluate the dam project and made a report in 2013. The IPoE report that the dam is up to international standard, that it is of high quality; and that the safety of the dam should not be an issue of

worry. The Egyptian experts duly signed the report alongside the rest of the IPoE members. Therefore, the Egyptian government has no credible reason or evidence to claim that the dam-building process is weak.

The IPoE didn’t come to this conclusion on its own, they first analyzed all 153 documents Ethiopia has

been using throughout the design and construction process. Additionally, IPoE members made an onsite visit to the dam site and inspected the setup in person, confirming that the dam meets international standards. I find the safety-related objections to the dam prejudicial, be it misguided.

On the occasion of the completion of the third filling of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) Horn Review discussed with Professor Yacob Arsano the technical, cooperative, and policy issues surrounding the dam.

Share

ከህዳሴው ግድብ ሶስተኛው ሙሌት በኋላስ?

ይህ ርዕስ በህዳሴው ግድብ ጀርባ ካለው በቢልዮን ከሚቆጠረው ውሀ ሊበልጥ የሚችል ዝርዝሮች የያዘ ርዕስ ነው ማለት ይቻላል! በህዳሴው ግድብ ላይ እውቀት ያላቸው ፍትሃዊ ባለሞያዎች ይህ ርዕስ ልክ በሱዳንና በግብፅ ወንድሞቻችን ላይ እደሚዘንበው ዝናብ አስፈላጊ መሆኑን በአንድ ድምፅ ተስማምተዋል።

ሳይንሳዊና ቴክኒካል ትንተናዎች ኢትዮጵያ ለጎረቤት ሀገራትና ለአለም አቀፉ ማህበረሰብ የገባችው ቃል ማረጋገጥ ካልቻሉ በቴሌቭዥን እና በተለያዩ ሚድያዎች ከመታየት ውጭ ምንም ነገር አላበረከቱም ማለት ይቻላል።

እሁን ለአስርት አመታት አልፎ ተርፎም ለዘመናት አብረን የተጓዝንበት መስቀለኛ መንገድ ላይ ነን። ያለፉት ዓመታት ያጋጠሙን ችግሮች ሁሉ ምንም እንኳን ባያስታውቀንም ይበልጥ እንድንቀራረብ አድርጎናል።

እናም በማንኛውም መልኩ የአንዱ የጠይሟ አህጉራችን ክፍል ድል ቢያገኝ፣ ደስታው ሌሎቹን የአህጉሪቱ ክፍሎች ሁሉ ያዳርሳል።

የበላይ መሪ የሆነች ትልቅ ተስፋ ያላት አህጉር አለችን …

አፍሪካ… የአለም ገነት…

ታዲያ ያለ ኢትዮጵያ ግብፅ እና ሱዳን የምንኮራበት አፍሪካ ልትኖር ትችላለችን??

የሰላም መርከቦች በአቢሲኒያ ከፍታዎች በጥቁር አባይ ዳርቻ ላይ አርፈው ኢትዮጵያዊያን ከግብፅና ከሱዳን ጋር ውህደት፣ ትብብር እና የጋራ ተጠቃሚነት እንዲኖር ጥሪ አቅርበዋል።

እኔ እዚህ የእነዚህን ስማቸው ብቻ የሚበቃ ሶስት ሀገራት ታሪካዊ ታላቅነት ለመዘርዘር አይደለም የቀረብኩት። በጌታ ፈቃድ ሦስተኛው ሙሌት ከተጠናቀቀ በኋላ አድማሱ ተከፍቶ ከመጣላት እና ካለመግባባት ይልቅ ትብብር እና አንድነት ከረጅም ጊዜ በፊት መጀመር እንደነበረብን ግልፅ ያደርግልናል። እነዚህ የብልጽግና እና የዘላቂ ልማት ሰንደቅ ዓላማዎች የሚውለበለቡባቸው አድማሶች ናቸው።

ከሦስተኛው ሙሌት በኋላ፣ አሁንም ያልተስማማንባቸውን ነጥቦች መከለስ ይጠበቅብናል። የህዳሴ ግድቡ አስከፊ አደጋ ነው እያለ ጉዳቱን ሲጠብቅ የነበረ አሁን በተጨባጭ የህዳሴውን ግድብ ጥቅምና አዋጭነት መዳሰስ ችሏል!

እንዲሁም የህዳሴው ግድቡ ካለቀ በኋላ ጥማትን እና ሞትን ሲጠብቅ የነበረ ሁሉ። በአላህ ፈቃድ ዉሀው ኤሌክትሪክ ካመረተ በኋላ የህዳሴው ግድብ በሮች ዉሀው በአግባቡ እንዲደርሳቸው አድርጎ ተስፋ የቆረጠውን ሁሉ በኤሌክትሪክም በውሀም ማስደመም ችሏል።

የክፋት መንገዶች ይፈርሳሉ የመልካምነት መንገዶች ጸንተው ይቆያሉ። ስለዚህ በግብፅ እና በሱዳን ያላችሁ ወንድሞች ለሀገራችንና ህዝቦቻችን ወደሚጠቅም ትብብር እንድትመጡ ጥሪ አቀርባለሁ። ያለፈውን አልፈን አሁን ያለውን በጋራ እንገንባ።

የአገሮቻቸውን ጥቅም ከግለሰቦች ጥቅም በላይ የሚያሳስባቸው አገሮች እንዴት ልዩ ናቸው? እስኪ ጮክ ብለን እንበል፡- የህዳሴው ግድብ የሚያስተሳስረን ፕሮጀክት ነው።

Share

ماذا بعد الملء الثالث لسد النهضة ؟

عنوان تربعت تحته مليارات التفاصيل التي قد تفوق مليارات المياه في سد النهضة

لقد أجمع العارفون العادلون في قضية سد النهضة. منه على جدواه التي تنهمر كما الأمطار على أشقائنا في السودان ومصر

وقد تظل التحليلات العلمية الفنية لا تراوح مكانها خلف شاشات التلفاز ووسائل الإعلام بمختلف أشكالها وألوانها إذا لم تثبت صحة الوعود الإثيوبية لدول الجوار والأسرة الدولية

إننا اليوم في مفترق طرق سلكناها سويا لعقود أو حتى قرون من الزمان

فكافة الإشكاليات التي خُضنا غمارها خلال السنون الغابرة جعلتنا أكثر قربا من بعضنا البعض حتى وإن لم نشعر بذلك في حقيقة الأمر

ولئن كان النصر حليفا لبقعة من بقاع قارتنا السمراء في أي أمر كان فإن فرحة الظفر به تتسكع في كل بقاع القارة كيفما شاءت لتحتل كافة البقاع الأخرى

وإن لم تبلغ مرادها هذا فإنها تحتفي بما

استطاعت احتلاله …

قارة واعدة قائدة سائدة …

إفريقيا … جنة الدنيا …

وأي إفريقية نتباهى بها دون إثيوبيا ومصر والسودان ؟

لقد أرست مراكب السلام دعائمها على مرتفعات بلاد الحبشة في ضفاف النيل الأزرق ليطلق ربانها الإثيوبيون دعوات التكامل والتعاون والمنفعة المتبادلة مع مصر والسودان !

ولست هنا بصدد سرد العظمة التاريخية لكل دولة من الدول الثلاث ، فيكفيك من عظمتهن اسم كل منهن

وحينما يتم الملء الثالث تتفتح الآفاق بإذن ربها لتبرز لنا كيف أنا بحاجة إلى التعاون منذ أمد بعيد منا إلى التصارع والتغابن

إنها آفاق تلوح في فضائها رايات الإزدهار والتنمية المستدامة

وبعد الملء الثالث يقتضي بنا مراجعة أوراقنا التي لازلنا نراهن عليها

فمن كان يقول بأن سد النهضة خطر محدق قد بات يلمس واقعيا منافع السد وجدواه بعد أن كان يرتقب ضره وأذاه !

ومن بات يرتقب العطش على إثر قيام السد أسعفته بوابات سد النهضة بماء أجراه الله بإذنه وقوته بعد أن أمره الله بتوليد الطاقة من ماء غير آسن ، فأبهر اليائس بماء وكهرباء بعد أن ارتقب العطش والبوار …!

أواصر الشر تتفكك وأواصر الخير تدوم ، فهلموا أيها الأشقاء في مصر والسودان نحو التعاون إلى مافيه صلاح بلداننا وشعوبنا

لنتجاوز الماضي ونبني الحاضر معا فما أرقى الأمم التي تغلب مصالح أوطانها على مصالح أفرادها ولنقل بصوت عالِ :

سد النهضة رابطة تجمعنا

دمتم بخير

Share

A Comparative Analysis of Cybersecurity Capabilities of the Nile Lower-Riparians (Part II)

A Comparative Analysis of Cybersecurity Capabilities of the Nile Lower-Riparians (Part II)

Abdijabar Yussuf Mohamed

About the Author

Abdijabar Yussuf Mohamed is a graduate of the Schwarzman Scholars Program in Beijing, China where he obtained his Masters in Global Affairs. Previously, he obtained a Bachelor’s degree in Computer Science from Middlebury College in Vermont, USA. As a Middlebury undergraduate, he was a Kathryn Davis Fellow for Peace & an exchange/associate student at Keble College, Oxford University in the U.K. He previously worked as Artificial Intelligence (AI) policy researcher and cybersecurity engineer. He currently researches the intersection between cybersecurity and public policy. His research interests include cybersecurity and cyber policy; AI & Data Science; Sino-Horn of Africa (HoA) relations; data-based (empirical) study of political violence in the Somali Region of Ethiopia.

Abstract

This article attempts to investigate Ethiopia’s cyber prowess relative to Egypt’s and, albeit to a lesser extent, that of Sudan. Of the three countries, evidence shows Egypt as the nation, among the three, has the superior cybersecurity regime. Ethiopia is ahead of Sudan but falls significantly behind Egypt. Additionally, Egypt has a National Cyber Strategy while Ethiopia and Sudan are yet to adopt robust and sound cybersecurity strategies that advance multi-stakeholder collaboration in the security, public, and private sectors. Additionally, Egyptian elite ethical hacker teams are ahead of Ethiopian and Sudanese ethical hackers in the international “cyber Olympics”. This article concludes with policy recommendations for building a cyber-resilient Ethiopia in which the national critical infrastructures such as the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) are protected from foreign cyberattacks.

In part I of“The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) as an African Cyberwarfare Front: A Simplified Cyber Attack Scenario & Some Plausible Cyber Attack Consequences”, this article illustrated what a simplified cyberattack scenario on the dam’s command & control (C2) involves and the plausible cyber-physical impacts of a cyberattack on the riverine Benishgul Gumuz Region (BGR) communities and the power grid system. These consequences include devastating power outages, future loss of life due to water poisoning, and reduction of the dam’s computer infrastructures to a global cybercrime station for local and international cybercrime syndicates. Part II will focus on assessing Ethiopia’s cyber capabilities vis-à-vis Egypt and, to a lesser extent, Sudan. After a brief discussion of a simple methodology & limitations, this article provides a discussion on the Global Cybersecurity Index (GCI) ranking of the three countries.

1. Methodology & Limitations

This is an underinvestigated topic and, as a result, there is little previous body of work upon which to build. Due to limiting legal and security reasons, first-hand data on the full extent of each of these countries’ cyber talent pools. Such data falls into the realm of classified intelligence world and it is not my intention as an “objectivity-seeking researcher” to even attempt to seek data that could be, in any shape or form, construed to undermine the respective national security laws that limit access to such critical data. Notwithstanding the dearth of first-hand data, there are useful talent data availed by the GCI ranking and CyberTalents, an independent platform that competitively nurtures global cybersecurity talent through organizing an annual national and regional Capture the Flag (CTF) competition. A CTF in computer security is a competitive exercise in which individuals and teams compete to find “flags” that are secretly obscured in deliberately vulnerable programs or websites. It is a way to determine expertise in hacking within the confines of the law. CyberTalents provides Jeopardy-style CTFs in which competing teams are presented with several challenges of varying complexity levels. The challenges are drawn from ethical hacking categories including, but not limited to, network security, web security, digital forensics, and reverse engineering. Teams can either compete independently or collaborate to form a national team.

2. Commitment to National Cyber Strategy: Egypt and Ethiopia

There are many tools for assessing a country’s commitment level to cybersecurity. This article will refer to the GCI, arguably the most reliable assessment tool for understanding how much emphasis a given nation places on advancing cybersecurity. The GCI is computed by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), the specialized United Nations (UN) agency responsible for matters pertaining to information and communication technologies, to assess the level of commitment to cyber development of its 193 member states and the State of Palestine. First launched in 2015 and rooted in ITU’s Global Cybersecurity Agenda, the GCI is based on five pillars that determine the intrinsic building blocks of a national cybersecurity culture: legal, technical, organizational, cooperation, and capacity-building measures.

According to the 2021 GCI index, Egypt is one of the cyber powerhouses in the Global South. In global rankings, Egypt scored 95.48% and claimed position 23 out of 182 surveyed countries. In the same year, Sudan scored 35.03% (corresponding to position 102 out of the 182 surveyed countries) whereas Ethiopia scored a dismal 27.74% and position 115 out of the 182 surveyed countries. There are, however, other regional rankings for the Middle East and Africa (MENA) and Africa that respectively included and omitted Egypt.

Given the vastness of the five pillars of the GCI, this article will use two key considerations as our yardstick: national cyber strategy and technical readiness, to fully understand how Ethiopia’s cyber capabilities compare to the two riparian downstream states of Egypt and Sudan

3. National Cyber Strategies: Egypt and Ethiopia

A national cybersecurity strategy (NCSS) refers to a high-level plan of action that is designed with the primary objective of enhancing the security and resilience of a nation’s critical infrastructures. It is essentially a top-down approach that works towards entrenching cybersecurity in critical infrastructures in line with a range of national objectives that are aimed at being attained within the limits of a given timeframe. The next section assesses the national cyber strategies of Egypt and Ethiopia. Due to the sparse availability of reliable cyber strategy information, Sudan is not discussed in this section.

3.1 The Case of Egypt

Egypt has a constitutionally-mandated National Cybersecurity Strategy (2017-2021), an action plan for the period between 2017 and 2021. This strategy involves several key programs that support Egypt’s strategic cybersecurity objectives. It acknowledges the most significant threats and challenges facing the nation’s critical infrastructures – specifically the energy sector, the information communication technologies (ICT) sector, the transportation sector, the health sector, etc. To achieve the security of these critical infrastructures, the strategy greatly emphasizes the distribution of roles among the various government agencies, businesses, civil society, and the private sector. To implement this strategy, Egypt has the Egypt Supreme Cybersecurity Council (ESCC). Developed under the auspices of the Ministry of Communications and Information Technologies (MCIT), ESCC reports to the cabinet and MCIT. It is made up of key stakeholders involved in national critical infrastructure management including the concerned government agencies, professional experts from the private sector, educational institutions, think tanks, and research scholars. The ESCC is expected to update the strategy and shepherd coordinated efforts aimed at safeguarding the national critical infrastructure from internal and external cyberattacks(National Cybersecurity Strategy 2017-2021, 2017).

3.2 The Ethiopian Case

For a very long time, Ethiopia has been trailing its peer nations in technological development. Since the 2006 creation of the Information Network Security Agency (INSA), the Ethiopian government has accorded special attention to cybersecurity policy. Since then, the government of Ethiopia approved two key proclamations – the 808-2013 and 1072-2018. As a result of these proclamations, in 2011, Ethiopia formulated a cyber policy. This policy is still under review and the nation lacks a comprehensive national cybersecurity strategy that guides coordinated efforts at combatting cyberattacks. In addition to the lack of political will to implement a national cybersecurity policy and implementing mechanism, there are two major challenges that the nation faces. The first one is a lack of awareness among the citizenry on what cybersecurity entails and its significance to the nation’s critical infrastructures. Second, is the lack of consideration of the international ISO 27001 cybersecurity standards, the international standard for information security (Markos, 2022).

4. CTF Cyber Supremacy Battle: Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan

One way of measuring a country’s cyber power is by scrutinizing the existing cyber talent. Because it is the cyber talent that undergirds a nation’s cyber offensive and defensive capabilities, it is worthwhile to comparatively analyze how that given country compares to its potential digital battle enemies. In this case, we are interested in fathoming how the existing Ethiopian cybersecurity talent compares to those of Egypt and Sudan.

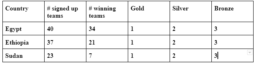

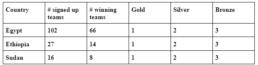

CyberTalents previously organized national CTFs for Egypt and Sudan but Ethiopia had its first national CTF (organized by CyberTalents) in 2020. Given that the 2022 competitions are yet to be held, we considered the available CTF data for 2020 and 2021. As indicated in tables 1 and 2 below, Egypt is ahead of both Sudan and Ethiopia in both participation & winning teams. In 2020, 40 Egyptian teams signed up to compete, 34 of whom successfully solved some of the challenges. In the same year and competition, Ethiopia fielded 37 teams. Out of the 37 teams, 21 teams won points.

Sudan, on the other hand, had 23 participating teams. Only 7 of the Sudanese teams won points.

Similarly, in 2021, Egypt had 102 participating teams and 66 winning teams; Ethiopia had 27 teams and 14 winning teams; Sudan had 16 teams with only 8 of the teams emerging as winners. Comparing the statistics of the two years, notice that Egypt’s participating and subsequently winning teams dramatically improved. In 2021, Egypt had 62 more participating teams and 32 more winning teams than in the year 2020. Contrarily, Ethiopia’s participating teams dropped by 10 and as a result, the previous year’s (2020) winning teams declined by 7. Similar to Ethiopia’s dismal performance in 2021, Sudan had 7 participating teams less than in the year 2020 and 1 more winning team than 2020. In both years, all three countries tied in high-level accolades (gold, silver, and bronze). Hence, these awards are not differentiating factors.

Table 1: The 2020 National CTF competitions data for Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan

Table 2: The 2021 National CTF competitions data for Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan

Going by the tabular data above, Egypt boasts of a more active and robust cyber talent than both Ethiopia and Sudan. Coupled with the individual teams’ points for the three cases, we can conclude that Egypt is the cyber talent superpower among the three, followed by Ethiopia and lastly Sudan.

4.1 Tri-Nation CyberTalent CTF Competition Visuals

More self-explanatory details of the team pseudonyms, member pseudonyms, team leaders, specific winning time, points, award levels, etc. are demonstrated in figures 1-6 below.

Image 1: Ethiopia National Cybersecurity CTF 20204

Image 2: Egypt National CTF 20205

Image 3: Sudan National Cybersecurity CTF Competition 20206

Image 4: Ethiopia National Cybersecurity CTF 20217

Image 5: Egypt National Cybersecurity CTF 20218

Image 6: Sudan National Cybersecurity CTF 20219

5. Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

Based on the aforementioned findings from the previous sections, one can conclude that compared to Ethiopia, Egypt is a relative cyber power.

While Sudan is a close competitor of Ethiopia in cyberspace, it does not outperform Ethiopia. Egypt’s cyber capabilities in combination with Sudan’s could mean devastating outcomes for Ethiopia in the event that these two countries collaborate in cyber operations against Ethiopia.

Such a scenario can occur if an international battle over the GERD extends beyond the domains of air and land to incorporate belligerent actions in the cyber realm. Bearing this in mind, it behooves Ethiopia to adopt evidence-driven policies that facilitate the following:

- (a) Quicken the process of adopting a comprehensive national cyber strategy that can protect the national critical infrastructures such as the GERD;

- (b) Create an Ethiopian Cyber Command, an organization composed of professional cybersecurity experts that can enhance Arat Kilo’s capability to & authority to guide and control cyberspace operations for strategic purposes;

- (c) Create a Cyber War Studies Program with experts that conduct research in cyber war simulation, cyber war games and defensive technical posture for the protection of the national critical infrastructures;

- (d) Provide support to cybersecurity & cyberwarfare researchers at both public and private universities;

- (f) Integrate a cybersecurity education into the national and regional curricula. Egypt enjoys a democratized higher education that cheaply provides cybersecurity education;

- (g) Provide support for cybersecurity hackathons, conferences, and journals at Ethiopian universities and colleges.

References

- National Cybersecurity Strategies. (n.d.). [Topic]. ENISA. Retrieved September 2, 2022, from https://www.enisa.europa.eu/topics/national-cyber-security-strategies

- Markos, Y. (2022). Cyber Security Challenges that Affect Ethiopia’s National Security. Available at SSRN 4190146

- Mohamed, A. The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) as an African Cyberwarfare Front – Horn Review. (August 11, 2022). Retrieved September 2, 2022, from https://hornreview.org/the-grand-ethiopian-renaissance-dam-gerd-as-an-african-cyberwarfare-front/

- Egyptian Supreme Council. (2017). National Cybersecurity Strategy 2017-2021. https://www.mcit.gov.eg/Upcont/Documents/Publications_12122018000_EN_National_Cybersecurity_Strategy_2017_2021.pdf