Is the United States a better-suited ally than China? An Exploration of United States' Comparative Advantage in Africa

Is the United States a better-suited ally than China? An Exploration of United States' Comparative Advantage in Africa

By Yirga Abebe

Yirga Abebe is currently a Ph.D. student at the Institute for Peace and Security Studies of Addis Ababa University. He holds a Bachelor of Arts Degree in Political Science and International Relations from Dire Dawa University in 2010 G.C and a Master of Arts Degree in Peace and Security Studies from the Institute for Peace and Security Studies of Addis Ababa University in 2014 G.C. Yirga has more than 10 years of professional experience in education and research in Ethiopian institutions of higher learning. He was a lecturer at Wollo University, Department of Peace and Development Studies, from September 2018-January 2021, and Jigjiga University, Department of Political Science and International Relations, from September 2010-August 2018. In addition to teaching, Yirga is actively engaged in conducting research on various themes at local, national, and regional level initiatives including customary conflict resolution, pastoral conflict management, conflict-induced displacement, women & election, parliament, and conflict management, peacebuilding, conflict trends, and geopolitical dynamics.

Africa has long been a center of intense rivalry between major powers. The continent has one of the world’s fastest-growing populations, the world’s most diverse ecosystems, abundant natural resources, and one of the largest voting blocks in the United Nations Assembly. The United States and China have been vying for political, economic, and regional influence in Africa since the early 2010s; it has, in recent years, intensified and brought ideological and geostrategic divisions to full display. The history and current state of relations that the two countries have with Africa are vastly different, both in the nature and magnitude of their engagements.

The US and Africa have a long and tumultuous history; since the second half of the 20th century, the relations between the US and Africa have gone through at least three major phases each with different features: during the Cold War, during the transitional period between 1990 to 1998, and after 1998. On August 2022, the United States adopted a new strategy towards Sub-Saharan Africa. Articulating a new vision for a 21st Century U.S.-African Partnership, the strategy aims to pursue four main objectives in sub-Saharan Africa:

foster openness and open societies; deliver democratic and security dividends; advance pandemic recovery and economic opportunity; and support conservation, climate adaptation, and a just energy transition.

China’s activities in Africa date back to the continent’s pre-independence period, when ideologically driven Beijing supported liberation movements fighting colonial powers. Nowadays, China is Africa’s largest trading partner, hitting $254 billion in 2021, exceeding by a factor of four US-Africa trade. China has become a preferred investment partner, a source of accessible loans for African countries across the board. Chinese funds back a wide range of projects from transportation to energy and minerals, medicine, agriculture, and telecommunications. However, these engagements are not without certain drawbacks.

For Africa, both the US and China have come up with their own comparative advantages/benefits. These factors would also benefit African countries and are the main reasons why African countries should favor closer ties with the United States than with China. What follows is a brief discussion of the US’s comparative advantages to the African continent at large.

Demographic factors

There is a large number of African descent living in the USA. This has a long history tracing back to the trans-Atlantic slave trade between the 16th and 19th centuries. It is indicated that 12% of the USA population, around 43 million, are of African descent.

It is estimated that over 28.3 million sub-Saharan Africans reside outside their countries of origin. Of these, while about 17.8 million (63%) lived elsewhere within the region, the United States is the top destination for sub-Saharan Africans outside the region. There are approximately 2.1 million sub-Saharan African immigrants who resided in the United States in 2019. 53 % of these immigrants came from Nigeria, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, or Somalia. On the other hand, there are 381,000 immigrants in the United States from North African countries mainly Egypt, Morocco, and Sudan. In comparison, the number of Africans in the USA is by far greater than an estimated 500,000 African migrants that live in China, many of which are merchants. This led the USA to have an advantage over China in its engagement in Africa.

African’s positive perception of the US is slightly greater than China

According to a survey conducted by Afrobarometer in 2019 and 2020 in 18 African countries, China and the United States are placed in roughly equivalent positions as external influencers. Asked about their perceptions of the economic and political influence of the two powers, 59% of African respondents viewed China somewhat, or very, positively and 15 percent viewed China somewhat or very negatively. The comparable numbers for the United States were similar: 58% in positive and 13% in negative view. The same study reported that, when respondents were asked to name the best national model for development, 32% cited the United States, and 23% named China. Moreover, many scholars anticipate that Africans’ positive perceptions of the United States may continue to increase during the presidency of Joe Biden. This positive perception that Africans have towards the United States, somehow greater than China, will be an advantage to be utilized while engaging in Africa.

The spread of democracy, human rights, and civil societies

The US is best known for safeguarding liberal principles and institutions. The promotion of democracy, human rights, and civil societies has been an integral part of the US’s domestic and foreign policies. This in turn contributes to the spread of these values and institutions across Africa. This has enabled to empower the people so that they can exercise their power to elect and scrutinize their governments. It makes it somewhat more difficult for African governments to get away with blatant and excessive abuses of power in due course of governing. As many of the public services in Africa are not only provided by the government, the emergence of local/national/international civil societies in African countries, which is the by-product of the US’s engagement, will fill this vacuum.

On the other hand, Chinese engagement in Africa is often criticized for lack of transparency as many business practices are claimed to be fraudulent, abusive, and corrupt. Similarly, China is also accused of undermining the strengthening of democratic institutions and governance in Africa as it continues to invest in countries with governance challenges such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Conflict resolution and security diplomacy

The US usually assumes a larger diplomatic role in the overall efforts to resolve African conflicts. Despite its ever growing influence and increasing commercial engagement, China’s diplomacy has traditionally kept a non-partisan stance concerning inter and intra-state conflicts, and their resolution attempts, in Africa.

It is stated that although Beijing did appoint a special envoy for the Horn of Africa earlier in 2022, it has not been active in diplomacy surrounding the war in Northern Ethiopia as might be expected given its heavy investment in the country. While the African Union has taken the diplomatic lead, the United States was playing both a public and behind-the-scenes role in Ethiopia.

China has traditionally adopted a “non-interference” policy in African and global conflicts. However, this policy seems to have evolved with its new Belt Road Initiative (BRI) over the past 10 years. In February 2023, Beijing launched its Global Security Initiative, with the aim of “peacefully resolving differences and disputes between countries through dialogue and consultation”.

The US has a strong military and security presence in Africa. According to the US African Command, there are a total of 29 US military bases located in 15 different countries in Africa in 2019. These bases are categorized as an “enduring footprint” (a permanent base) and those with a “non-enduring footprint” or” (semi-permanent or contingency base). On the other hand, China established its first overseas military base in Djibouti in 2017. In general, the US has more leverage in terms of conflict resolution and security diplomacy than China which is known for its emphasis on economic diplomacy. This will enable to maintain military and security ties between Africa and the US.

Strong humanitarian engagement

The US has been more strongly engaged in humanitarian sectors, than Chinese, in sub-Saharan Africa. The U.S. gave out $97.67 billion between 2000 and 2018 in Official Development Assistance to sub-Saharan Africa, with infrastructure projects (48 percent of total aid) and humanitarian aid (26 percent) being the top priorities. The health sector was given $6 billion, the agriculture sector received $4.2 billion, and $3.5 billion was committed to education. In Fiscal Year 2021, USAID and the U.S. Department of State provided $8.5 billion of assistance to 47 countries and 8 regional programs in sub-Saharan Africa. China’s global foreign aid expenditure has reached $3.18 billion in 2021. Between 2013 and 2018, 45% of China’s around $26 billion foreign aid went to Africa, much of this aid went to transportation, energy, and communication sectors. Unlike the Chinese development priorities in Africa, United States development efforts place greater emphasis on health, education, and other humanitarian sectors.

Diaspora Remittances

There is a large number of African diaspora in the USA. According to Migration Policy Institute (2022), the number of sub-Saharan African diaspora in the United States is more than 4.5 million. The figure is expected to increase considering the number of Diasporas in the USA from North African states. The African diaspora living in the US, Europe, and elsewhere send back significant amounts in remittances to the continent. World Bank figures show that there is a total of $95.6 billion in remittance flows to Africa in 2021, of which $46.6 billion went to North Africa and $49 billion to sub-Saharan Africa. The extent of remittance is more favorable than the official development assistance to Africa of $35bn and foreign direct investment to sub-Saharan Africa of $88bn in 2021.

Chinese debt trap policy

Acknowledging this role, the African Diaspora has been among the priority issues in the US-Africa Leaders’ Summit which was undertaken in Washington DC on December 2022. It is also pronounced that the Biden administration will provide targeted support to small- and medium-sized businesses “with a specific focus on the African diaspora and their businesses and investors across the United States”. Therefore, the African diaspora, their business, and remittances will serve as an entry point for US’s comparative advantage over China related to Africa.

China is undoubtedly Africa’s largest bilateral creditor and a crucial partner in pioneering infrastructure development projects. Chinese loans have resulted in a significant debt held by African states. It is stated that overall external debt held by governments in the continent has doubled in two years, from a 5.8 percent average of government revenue in 2015 to 11.8 percent in 2017. Some African nations do have extensive Chinese loans and are suffering from out-of-control debt, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, high-interest rates, and other factors. While maintaining its image as a friend of developing nations, the extensive Chinese loans made to African countries will create the possibility of forced repayments, another headache to the continent’s development.

Some Pitfalls of Chinese Engagement in Africa

China is often criticized for an unfair and lack of a long-term strategy when engaging Africa. Compared with the US, the quality and standard of Chinese businesses in Africa is questionable. Its strategy is more about exploiting African natural resources than spurring the continent’s development, which also raises questions about sustainability for future generations in the continent and environmental concerns as well. In this regard, former President of the USA, Barack Obama, once said:

We don’t look to Africa simply for its natural resources. We recognize Africa for its greatest resource which is its people and its talents and its potential. We don’t simply want to extract minerals from the ground for our growth. We want to build partnerships that create jobs and opportunities for all our peoples that unleash the next era of African growth […]

While it is common to assume that China has been deeply engaged in Africa even surpassing the US, there is a repertoire of comparative advantages that the US offers to Africa. These stem from the US’ own strengths, as well as the pitfalls of Chinese engagement in the continent. These include factors related to demography, African perception, democracy, diaspora remittances, and strong engagement of the US in conflict resolution, security, and humanitarian-led diplomacy, on the other hand, China’s debt trap strategies and its trade practices in Africa present the United States as a better-suited ally.

Foreign Aid to Africa: The United States vs. China | The Borgen Project. April 2018.

Sino-African Migration: Challenging Narratives of African Mobility and Chinese Motives| China Focus. August 2021.

“A Brief History of U.S.-Africa Relations” in “United States-Africa Relations in the Age of Obama” | Cornell University Press Digital Platform.

Pentagon Map Shows Network of 29 U.S. Bases in Africa | The Intercept. February 2020.

The Eagle and the Dragon in Africa: Comparing Data on Chinese and American Influence | War on the Rocks.| May 2021.

The US and China in Africa: Competition or Cooperation? | Brookings. April 2014.

10 Things to Know about the U.S.-China Rivalry in Africa | United States Institute of Peace. December 2022.

US Strategy Toward Sub-Saharan Africa | The White House. August 2022.

Share

A Humanitarian Lifeline for Sudan’s Population: A Possible Ethiopian Role

A Humanitarian Lifeline for Sudan’s Population: A Possible Ethiopian Role

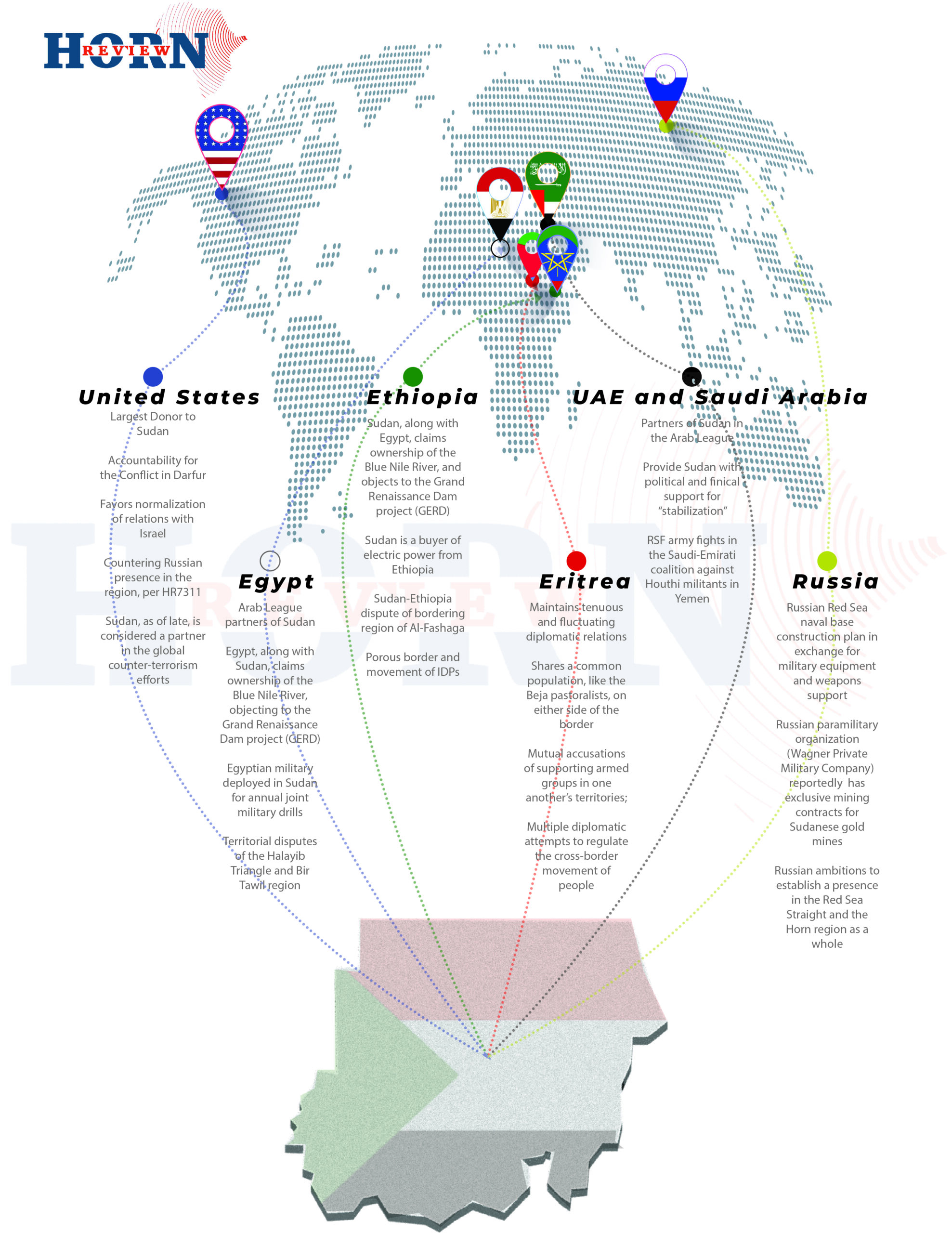

With a full-scale war being fought in urban centers, foreign states swiftly evacuating their nationals, depletion of food and basic necessities in conflict zones, and no apparent pathways for a return to peaceful political resolution, the humanitarian crisis in Sudan is progressively worsening with each passing day. A multitude of factors further heightens the complexity of this conflict: the multiplicity of external actors and interests, the direct involvement of neighbors like Eritrea and Egypt- and others in the Gulf Region- and the internationalization of the conflict among global actors like the US and Russia. These factors further weaken the role and position of regional actors and mechanisms like Ethiopia, the AU, and IGAD to spearhead diplomatic options for the political resolution of the conflict as they have in the past.

However, Ethiopia is the best-suited country in the region to play a decisive role if not in the political de-escalation between the military factions, and the amelioration of human conditions, particularly in mitigating the human toll as a result of the conflict. Tens of thousands of refugees have already fled the conflict via Chad, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Saudi Arabia; the latter via Port Sudan. Neighboring countries and humanitarian organizations are struggling to match the pace and urgency of the mounting humanitarian needs.

The route from Khartoum to Metemma is arguably the safest and most direct route to safety from the capital – given that the majority of this route is under the control of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) -particularly the route stretching from Gedaref to Metemma.

As a nation with a past mediatory role and close acquaintance with both parties to the conflict: Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (Hemmeti), Ethiopia is best positioned to be an interlocutor to facilitate humanitarian assistance. It is therefore essential for Ethiopia to consider forwarding itself as a principal country of asylum for Sudanese civilians fleeing the conflict and consider convening international partners to formulate a coordination mechanism to facilitate refugee reception and welfare measures.

This option might include:

-

- Establishment of a temporary reception center at Metemma with accommodation and essential care and services for arrivals;

- Application of expedited entry procedures for genuine asylum seekers;

- Coordination with the ICRC, UN, and both the SAF and the RSF leaderships to facilitate the movement of humanitarian convoys traveling between Khartoum and Mettema, and Metemma and Gedaref;

- Possible coordination with SAF to ensure security along the Gedaref-Metemma route.

Ethiopia is undoubtedly one of the countries to be directly and indirectly affected by the conflict; as it maintains the convening power within IGAD and the AU, Addis Ababa is therefore well positioned to promote, facilitate, and host multilateral diplomatic initiatives with the principal aim of aiding the Sudanese people and preventing a humanitarian calamity from unfolding.

Share

From Security Provider to a Security Vaccum? The Hasty Withdrawal of Ethiopia’s Decade-Long Peacekeeping Mission in UNISFA

From Security Provider to a Security Vaccum? The Hasty Withdrawal of Ethiopia’s Decade-Long Peacekeeping Mission in UNISFA

By: Kaleab Tadesse Sigatu1

Introduction

Ethiopia has been participating actively in UN peacekeeping missions since the 1950s up to now. The reasons were based on the sending regime’s intention, the nature of the armed forces, and the focus area of the deployment. The Imperial Ethiopian Government under Emperor Haile Selassie I (1930–1974) sent peacekeeping troops to Korea, Congo, and to the contested region of Jammu and Kashmir of India and Pakistan. The socialist military regime (1974–1991) did not participate in any peacekeeping missions at all. The post-1991 Ethiopian Government mostly focused on peacekeeping missions in Africa and contributed peacekeepers to Rwanda, Burundi, Liberia, Côte d’Ivoire, Central African Republic, Chad, Mali, Sudan, South Sudan, Somalia, and also in Haiti, and Yemen. Lastly, the new reformist government, which came to power in 2018, has made no policy change from the aforementioned regime toward participating in peacekeeping missions.

The Ethiopian National Defence Forces (ENDF) therefore acquired a paramount peacekeeping capability with the regional standard in training and experience gained through previous international peacekeeping deployments. This resulted in Ethiopia playing an important role in regional stability as the prevalent contributor to UN and AU peacekeeping missions, especially in Somalia, South Sudan, and Sudan.2 Even though Ethiopia’s military (peacekeeping) and peace mediating role is not without criticisms it became “a formidable force for peace, security, and stability in the Horn of Africa, and in Africa in general”.3 This is especially true concerning Ethiopia’s interventionist role in Somalia.4 Ethiopia’s first unilateral action in Somalia was in 1995 to remove the Islamic insurgent, Al-Ittihad Al-Islamiya (AIAI). In 1998 Ethiopia launched a second military intervention at the time of the Ethiopia–Eritrea war, following Eritrea’s effort – in collaboration with a Baidoa-based Somali warlord Hussein Aideed and involving the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) and the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) to open a second front.5 Ethiopia’s third intervention was in 2006, against the threat from the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) and supporting the Somali Transitional Federal Government. Lastly, Ethiopia joined AMISOM in 2014, simultaneously deploying troops outside the AMISOM command to support its troops under AMISOM.

Likewise, Ethiopia has been a part of the peacekeeping missions in Sudan and South Sudan for more than a decade. Ethiopia contributed police personnel for the United Nations Mission in Sudan (UNMIS) from 2005 until the independence of South Sudan in 2011. It is also a part of the United Nations Mission in the Republic of South Sudan (UNMISS), which is still optional since 2011. Since joining in 2014 Ethiopia has contributed around 2,000 troops to UNMISS making it one of the top five largest contributors.6 It also contributed around 20,000 mainly continent troops, in different rotations for the African Union–United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID), (2007–2020) in Sudan.7 Moreover, Ethiopia contributed the entire contingent troops to the United Nations Interim Security Force in Abyei (UNISFA), at the disputed border region between South Sudan and Sudan, which is the focus of this paper and discussed below. All missions make Ethiopia a ‘security provider’ in most of the conflict regions in the African continent, which is compounded by intra-regional and international intervention.8

South Sudan and Sudan and the conflict over Abyei

The north–south conflict in Sudan was between the mostly desert, largely Muslim and culturally Arabic North Sudan and the tropical, largely Christian or animist and culturally sub-Saharan Southern Sudan. The first Sudanese civil war happened between 1955 and 1972; it begins before the independence of Sudan from the Anglo– Egyptian colony and ended at the signing of the Addis Ababa Accord, an agreement that gave Southern Sudan autonomy, signed in Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia. However, in 1983, the government enforced Shari’a law on the south when President Nimeiry declared all of Sudan as an Islamic state, terminating the autonomous status of Southern Sudan, which triggered the second Sudanese civil war.9 It was the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) signed in 2005 that ended the civil war.

The CPA was signed between the government of Sudan and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLM/SPLA) after having continuous negotiations since 2002 under the auspices of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development(IGAD) and the government of Kenya.10 The CPA established a six-year interim period during which the southern Sudanese will have the right to govern affairs in their region; one of the major agreements of the CPA was the fact that Southern Sudan will have the right to vote for the referendum. The other CPA agreement was the resolution of the contested border region of Abyei, which gave Abyei special administrative status during the interim period. At the end of the six-year interim period, Abyei residents will vote in a referendum either to maintain special administrative status in the north or to become part of the south. The government of Sudan and SPLM/SPLA also agreed to share oil revenues from Abyei, to be split between the north and south with small percentages of revenues allocated to other states and ethnic groups.11

Consequently, South Sudan separated from northern Sudan and became an independent state after six years as per the agreement of the CPA on 9 July 2011. However, the demarcation of the border of the oil-rich Abyei region between South Sudan and Sudan became contentious because both states claimed it as their own territory.12 In addition, the South Sudanese referendum did not take place in Abyei because both sides failed to put it into practice, as they could not agree on who was eligible to vote.13

Political scientists argue that there is a likelihood of conflict between the secessionist or newly established and the former ‘mother’ state or rump on the territorial issue.14 This is true in the Horn of Africa in the case of Ethiopia and Eritrea and Somaliland and Puntland/Somalia. When a territory of a state breaks away and becomes an independent entity, the new land boundaries that emerge are often violently contested.

Jaroslav Tir in his study on interstate relations especially territorial disagreement between rump and secessionist states after a separation, put his argument as follows: Through the secession, the rump state has lost some of the territories it previously controlled to the secessionist state and may want a portion or all of it back. Conversely, the secessionist state may not be satisfied with how much land it has received and may desire even more of the rump state’s land. Finally, the secessionist state may set its sights on another secessionist state’s territory.

Land’s strategic value arises from its characteristics and/or location. Losing a high ground or an impenetrable swamp or desert may make the country easier to invade and thus undermine its defensive ability. Losing a piece of land containing resources such as ore deposits, ports, and so on undermines the rump state’s economic, and, by extension, military, capability. The desire of countries to pursue power is one of the cornerstones of the realist school of thought, and at least some realists view the role of territorial control as crucial to a state’s power.15

On the other hand, resource-related conflicts rose because of the geographical location of the resource. Anderson and Browne argue that the vast majority of the most significant oil fields so far identified in the Horn of Africa lie in troubled border areas and disputed territories. In addition to the case of this study, Abyei, the Ilemi Triangle and northern Kenya, the Lake Albert basin, the Ogaden, and the Sool region between Somaliland and Puntland are unresolved international disputes.16

In the case of Abyei, the indigenous population is the Ngok Dinka who supported the South Sudanese rebels during the civil war (1983–2005). However, every year Northern Misseriya pastoralists, who are aligned with Khartoum, migrate to Abyei in search of pasture. This migration and sharing of land and pasture created conflict between the two communities over scarce resources.17 The root causes of the Abyei conflict go back to the early 1900s when the people of Ngok Dinka were transferred in 1905 by British colonial authorities from Bahr el Ghazal to Kordofan (a northern province) for administrative reasons.18 During the first civil war that erupted in Southern Sudan in 1955, the people of the Abyei area joined the Southern resistance movement known as “Anya-Nya” with the aim of returning the administration of Abyei back to Southern Sudan.19 Later, the governments of both Sudan and South Sudan became heavily involved in the Abyei conflict, fighting to control oil fields in the area.

Figure 1: South Sudan, Sudan and the contested area of Abyei

Source: Sudan Tribune (2022b): op. cit.

The Abyei region is referred to by some as “an area which had been a symbol of peaceful coexistence and cooperation has become a point of confrontation and conflict that is both identity-based and resource-driven”.20 Others say Abyei is “Sudan’s ‘Kashmir’”,21 and “a breaking point of Sudan’s Comprehensive Peace Agreement”.22 The Chief of the Ngok Dinka of Abyei, Deng Majok said “the thread that stitches the north and south of Sudan together through Abyei”.23

United Nations Interim Security Force in Abyei (UNISFA) and the Ethiopian Deployment

The Security Council passed a Resolution on 27 June 2011, based on the agreement between the government of Sudan and the SPLM on temporary arrangements for the administration and security of the Abyei Area reached on 20 June 2011 in Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia. The 2011 resolution established UNISFA with the strength of 4,200 military personnel, 50 police personnel, and appropriate civilian support.24 The resolution also pointed out that both the government of Sudan and the SPLM requested the assistance of the Ethiopian Government, which resulted in the exclusive responsibility of Ethiopian troops to monitor the area by contributing the leadership with both the head of mission and force commander for UNISFA.25

The reason was that Sudan would not accept non-African troops and South Sudan had thus asked IGAD for additional mediation support, and the need for a third party to monitor the flashpoint border, troops from Ethiopia.26 This can be considered a diplomatic success for Ethiopia to have smooth relations with both states and both accept Ethiopia’s singular mono-nation mission to deploy its contingent.

The resolution decided the demilitarisation of the Abyei area except for forces other than UNISFA and the Abyei Police Service. At the beginning of the mission, as of August 2011, Ethiopia contributed a total of 1,707 personnel, 1,634 contingents, and 73 experts to the mission. At the beginning of the mission, the total amount of personnel was 1,814; including Ethiopia only four countries contributed contingents: Egypt 11 officers, India 36 officers, and Zambia 12 officers. This means Ethiopia contributed 97% of the total contingent.27

UNISFA’s deployment was on 22 July 2011, after one month of the authorization of the mission. The UNSC Resolution 1990 also came out swiftly, three days after the conclusion of the Addis Agreement. Under normal circumstances, the deployment of peacekeeping missions takes a long time, as it requires convincing troop-contributing countries, mobilizing resources required, and deploying them on the ground.28 However, in the case of UNISFA, Ethiopia’s contribution came swiftly. Osterrieder et al. describe the deployment as follows:

The deployment of troops for UNISFA took place significantly more quickly than is usually the case (with UN peacekeeping operations). Only one month after its authorization, almost 500 troops had been deployed to the Abyei region. Operations started on 8 August 2011, while patrols began at the end of August 2011. The fact that UNISFA troops were drawn from one country, Ethiopia, helps to explain this prompt deployment. Indeed, the Ethiopian troops were ready to be deployed even before the UN Security Council authorized the mission. The land route from Ethiopia to Abyei was used to transfer troops within a week. Some existing UNMIS facilities were also used for UNISFA. The Ethiopian troops did not require the living standards normally necessary for UN missions. Temporary housing in tents was an efficient way to ensure the timely deployment of troops. Only a few months after its authorization, the UN Secretary-General declared that the mission was “in a position to secure the Abyei area,” and thus able to fulfill its mandate.29

At the time, Ethiopian ongoing peacekeeping mission participation in both Sudan (Darfur) and South Sudan made the deployment prompt. In May 2013, the Security Council, by its resolution 2104, increased UNISFA’s military strength up to 5,326 peacekeepers, as requested by Sudan and South Sudan.30 By the end of the year, 4,102 military personnel were deployed, 17 individual police, 129 experts on mission, and 3,956 contingents. Ethiopia deployed 7 individual police, 78 experts on mission, and 3,930 contingent troops. This means 99% of the contingents are from Ethiopia. Even though 20 countries contributed contingent troops, no state contributed more than two personnel.

In May 2018 Security Council Adopts Resolution 2416 (2018), extending the mandate of UNISFA in Abyei. It also decided to reduce UNISFA’s authorized troop ceiling to 4,500 until 15 November 2018, and that as of 15 October 2018, that ceiling would decrease further to 3,959 unless the aforementioned mandate modifications were extended.31 However, the mission continued without the decline in size. As of December 2018, 100% of the contingent troops were from Ethiopia.

One of the main reasons Ethiopia took the initiative to deploy its troops to the disputed region right away, aside from the fact that Ethiopia has a long history of taking part in peacekeeping missions, was the fact that the negative effects of a full-fledged war between Sudan and South Sudan will not only be felt by the two countries but also by the entire region, including Ethiopia. At the time, the Peace and Security Council of the AU acknowledged the Ethiopian Government for its effort in its communiqué in November 2011, as follows:

The Council also expresses its deep appreciation to the Government of Ethiopia, particularly Prime Minister Meles Zenawi, Chair of IGAD, for its commitment and sustained efforts towards the promotion of peace and the resolution of the post secession issues, including the speedy deployment of troops within the framework of the UNISFA.32

Some experts argue that such peacekeeping involvement of a neighboring state runs counter to a longstanding, although unwritten, principle that UN peacekeeping missions should seek to avoid deployment of troops or police from ‘neighbors’ in order to mitigate the risks associated with these countries’ national interests in the host countries.33 Moreover, in 1958, Hammarskjold warned about the dangers of deploying peacekeepers from states with direct interests in the conflict.

In order to limit the scope of possible differences of opinion, the United Nations in recent operations has followed two principles: not to include units from any of the permanent members of the Security Council; and not to include units from any country which, because of its geographical position or for other reasons, might be considered as possibly having a special interest in the situation which has called for the operation.34

However, UNISFA was able to manage effectively to keep the area of Abyei free from armed infiltration by Ngok Dinka activists, Misseriya cattle herders, or security forces from Sudan or South Sudan.35 According to Osterrieder et al., the fact that Ethiopian troops understand the culture, local situation, and the conflict helped them to accomplish the peacekeeping well. Moreover, it is simpler to coordinate missions with a single nation’s military than it is to coordinate missions with numerous states that contribute forces.36 Nevertheless, there has been much progress made on political mechanisms to determine the final status of Abyei, demilitarise, and demarcate the border.37

Ethiopia’s involvement in Abyei also emanates from its foreign policy. Ethiopia has a strong strategic interest in the peaceful coexistence of Sudan and South Sudan and in upholding its good relationship with both countries. Instability in Sudan and South Sudan and the possibility of renewed conflict between the two states pose a threat to Ethiopia’s national security. Ethiopia also has economic interests in natural resources in Sudan and South Sudan. Ethiopia has been trying hard not to be involved in the internal affairs of the two counties. After the passing of the Meles Zenawi in 2012, the then-acting prime minister, Hailemariam Desalegn, confirmed Ethiopia would “maintain its neutral and principled support to the two brotherly countries’ effort towards resolving their dispute.”38

The Ethiopian Foreign Affairs and National Security Policy and Strategy states Ethiopia’s policy and strategy towards the Horn of African states as “…these countries have long-standing links with Ethiopia in such areas as language, culture, history, natural resources, and so on. Changes in Ethiopia affect them directly, and what happens to them has an impact on us”.39 Barry Buzan and Ole Wæver also confirm that conflict between and within the two Sudans could have both a direct and indirect spillover effect on Ethiopia, thus Ethiopia can be seen to have a genuine interest in peace in and between the two countries.40

The Ethiopian relations with South Sudan

Ethiopia’s relations with South Sudan began in pre-independence days when both the previous governments of Emperor Haile Selassie I and Colonel Mengistu supported the southern Sudanese secessionist movements most importantly SPLM. Ethiopia played a very important role in the independence of South Sudan. After its independence, Ethiopia has been actively involved in peace processes with Sudan in the case of Abyei and after the 2013 civil war broke out. Besides the spillover effect of the conflict to Ethiopia’s Gambella region, Ethiopia has a great advantage in a stable South Sudan in using South Sudan’s oil and market.

Ethiopia deployed more than 40,000 peacekeeping troops in both UNMISS, UNISFA, and CTSAMM in different rotations. Moreover, Ethiopia was actively involved in the efforts of IGAD to bring peace in South Sudan by appointing its former foreign minister the late Seyoum Mesfin, to lead an international mediation process. In 2015, President Salva Kiir of South Sudan met rebel leader Riek Machar in Addis Ababa for the first time to start a peace talk. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed also hosted both Salva Kiir and Riek Machar in Addis Ababa to initiate the talk in 2018. During the meeting, the Ethiopian Prime Minister’s Chief of Staff said, “…faced with the continued suffering in South Sudan, Ethiopia simply can’t stand by”.41

The Ethiopian Relations with Sudan

The relationship between Sudan and Ethiopia has been both harmonious and hostile. Though there is a long history of relations starting from the time of Axum and Merowe, in the modern history of Ethiopia, the relations go back to the Islamist Mahdist state (1885–1898)42 and the Christian kingdom Emperor Yohannes IV of Ethiopia (reigned from 1872–1889). Because of the Hewett Treaty in 1883, in which Ethiopia assisted Egyptian troops in Sudan during the Mahdist resistance movement against the Ottoman–Egyptian administration, the Mahdists made a revenge attack against Ethiopia in 1889; burned churches, and shattered the old capital of Gondar. The emperor marched to Sudan with his army to fight back the Mahdists but died in the Battle of Metemma in 1989.

During the reign of Emperor Haile Selassie I, the Ethiopian Government covertly gave aid to the Anya-Nya movement, a southern separatist rebel army formed from 1955 up to 1972.43 On the other hand, in 1972 the emperor negotiated the Addis Ababa Agreement between the Sudanese Government and the Anya-Nya. Ethiopia was the sole active black African actor to intervene in the Sudanese war, during the 1980s and early 1990s.44 The Ethiopian Derg Government (1974–1991) backed the SPLM/SPLA, hoping to retaliate against Sudan which served as a sanctuary, rear bases, and channels for the transmittal of military, food, and medical supplies for Eritrean secessionist rebel forces fighting the government.45 Besides having several safe houses in Addis Ababa for the SPLA leadership, military training was given to SPLA fighters at military camps in Ethiopia in addition to logistic support. The overthrow of Derg by the Eritrean and Tigrayian rebel groups in 1991 was a fortunate development for Sudan. The post-1991 Ethiopian Government led by the EPRDF had also an important part in the various mediation efforts through its role in the IGAD.46

However, with the arrival of Islamists in power in 1989, General Omar Hassan al-Bashir, backed by Hassan al-Turabi, and the 1995 assassination attempt of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak on a visit to Addis Ababa, which was backed by the Sudanese Government, damaged the relationship. Sudan’s involvement in Ethiopia to impose its Islamic ideology with the interest of creating its dominance in Ethiopia was another factor in the deterioration of the relationship.47 Later, the relationship between the two states improved after the visit of Omar Hassan Al-Beshir to Addis Ababa in 1999 “to normalize the relations between Ethiopia and the Sudan after passing through a period of difficulty in their diplomatic relationship”.48 This was followed by the visit of Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi to Khartoum in 2002. In the same year Ethiopia, Sudan, and Yemen initiated trilateral cooperation, the Sana’a Forum for Cooperation. By 2003, Ethiopia began importing oil from Sudan, and by 2009, Sudan supplied 80% of Ethiopia’s oil demand.49 More importantly, President Omar al-Bashir said in March 2012, his country supports the controversial Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam project, which both the downstream states Sudan and Egypt opposed when its construction was launched in 2011, claiming it will affect their water shares.50 In recent years, Ethiopia played an active role in Sudan’s political crisis after the military ousted Omar Al-Beshir in April 2019. Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed mediated between Sudan’s Transitional Military Council and the civilian opposition.51

The rift between Ethiopia and Sudan

According to John Young, the biggest present-day threat to peaceful relations between the two states is internal instability, which has three components.52 First, the new governments in both nations are without a history of cooperation and are uncertain of each other; second, a lack of full control by both countries over their shared border areas; and third, doubts regarding the unity of the governments in both Khartoum and Addis Ababa.53 Moreover, historically Sudan’s closest relations have been with Egypt because the Nile encouraged similar forms of economy and trade, as well as the spread of the Arabic language and Islam; and noting Egypt nominally ruled Sudan in the Anglo–Egyptian Condominium.54

Most recently, the Nile River hydro politics and the border dispute in Al-Fashaga have played a major role, which led to Ethiopia’s untrustworthiness in the eyes of the new Sudanese Government in its peacekeeping operation in Abyei. These crises had a significant impact on Ethiopian peacekeeping operations and the reputation of the ENDF, as the Sudanese Government demanded that Ethiopian peacekeeping troops withdraw from UNISFA in Abyei. It was in April 2021 that Sudan’s Foreign Minister Mariam al-Mahdi declared that because of Ethiopia’s ‘unacceptable intransigence’ in the talks over the GERD and its decision to proceed with the second phase of the filling of its dam; and since the Ethiopian troops are massing on the eastern borders of Sudan, it is not conceivable for Ethiopian forces to be deployed in the strategic depth of Sudan.55

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) and the Nile hydro politics

The 2002 Ethiopian Foreign Affairs, National Security Policy, and Strategy document indicates that the issue of the Nile’s water poses an unsurpassable obstacle to establishing strong ties between Ethiopia and Sudan. The document states: “One of the causes for the deterioration of relations with the Sudan concerns the use of the waters of the Nile. In this regard, the agreement the Sudan signed with Egypt in 1959 excluded Ethiopia from the use of the river…”56 This is a clear indication that the Nile hydro politics has been a perpetual hiccup on Ethio–Sudan relations.

1Ph.D. student, University of Public Service, Doctoral School of Military Sciences

2 Christopher Clapham: The Horn of Africa. State Formation and Decay. London, Hurst & Company, 2017. 179.

3 Tekeda Alemu: The Conundrum of Present Ethiopian Foreign Policy. In Search of a Roadmap for Ethiopia’s Foreign and National Security Policy and Strategy. CDRC, January 2019.

4 Debora V. Malito: The Persistence of State Disintegration in Somalia Between Regional and Global Intervention. Doctoral Thesis. Università degli studi di Milano, 2013.

5 Abdeta D. Beyene – Seyoum Mesfin: The Practicalities of Living with Failed States. Dædalus, 147, no. 1 (2018). 129.

6 United Nations: UNMISS Factsheet. United Nations, 10 June 2022.

7Kaleab T. Sigatu: Military Power as Foreign Policy Instrument: Post-1991 Ethiopian Peace Support Operations in the Horn of Africa. Ph.D. Dissertation in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Military Sciences. Budapest, University of Public Service, Doctoral School of Military Sciences, 2021.

8Redie Bereketeab: Introduction. In Redie Bereketeab (ed.): The Horn of Africa. Intra-State and Inter-State Conflicts and Security. London, Pluto Press, 2013. 3.

9John R. Crook: Introductory Note to the Government of Sudan and the South Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/ Army Abyei Arbitration Award. International Legal Materials, 48, no. 6 (2009). 1254.

10 Marina Ottaway – Amr Hamzawy: The Comprehensive Peace Agreement. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 04 January 2011.

11 Crook (2009): op. cit. 1257.

12Crook (2009): op. cit. 1257.

13Nadia Sarwar: Post-Independence South Sudan: An Era of Hope and Challenges. Strategic Studies, 32, nos. 2–3 (2012). 177.

14Sophia L. R. Dawkins – Bart L. Smit Duijzentkunst: Stable and Final? Arbitration of Land Boundary Disputes in Cases of State Secession. Proceedings of the ASIL Annual Meeting, 106 (2012). 143–146

15Jaroslav Tir: Keeping the Peace after Secession: Territorial Conflicts between Rump and Secessionist States. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 49, no. 5 (2005). 717.

16David M. Anderson – Adrian J. Browne: The Politics of Oil in Eastern Africa. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 5, no. 2 (2011). 395.

17Amira A. Osman: Conflict over Scarce Resources and Identity: The case of Abyei, Sudan. In Ulf Johansson Dahre (ed.): Resources, Peace and Conflict in the Horn of Africa. AReport on the 12th Horn of Africa Conference. Lund, Sweden, 23–25 Au gust 2013. 250.

18 Luka B. Deng: Justice in Sudan: Will the Award of the International Abyei Arbitration Tribunal Be Honoured? Journal of Eastern African Studies, 4, no. 2 (2010). 299.

19Deng (2010): op. cit. 299.

20John Prendergast – Brian Adeba: Abyei: Sudan and South Sudan’s New Chance to Solve Old Disputes. African Arguments, 21 October 2019.

21Roger Winter – John Prendergast: Abeyi: Sudan’s ‘Kashmir’. American Progress, 29 January 2008.

22 Douglas H. Johnson: Why Abyei Matters. The Breaking Point of Sudan’s Comprehensive Peace Agreement? African Affairs, 107, no. 426 (2008). 1–19.

23Francis Deng: The Man Called Deng Majok: A Biography of power, polygyny, and change. New Jersey, Yale University Press, 1986. 229.

24 Security Council: Resolution 1990 (2011). United Nations, 27 June 2011.

25 Sigatu (2021): op. cit.

26Report of the Chairperson of the Commission on the Effort and Activities of the African Union High-Level Implementation Panel on Sudan (AU doc. PSC/PR/CCCI, 30 November 2011).

27 United Nations: Troop and Police Contributors. United Nations, December 2018.

28Mehari Taddele M.: Keeping Peace in Abyei: The Role and Contributions of Ethiopia. ISS Africa, 28 October 2011.

29Holger Osterrieder et al.: United Nations Interim Security Force for Abyei (UNISFA). In Joachim A. Koops et al. (eds.): The Oxford Handbook of United Nations Peacekeeping Operations. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2017. 821.

30UN Security Council: Resolution 2104 (2013). United Nations, 29 May 2013.

31UN Security Council: Resolution 2416 (2018). United Nations, 15 May 2018.

32African Union: Peace and Security Council 301st Meeting: Communiqué. AU Peace and Security Council, 30 November 2011.

33Paul D. Williams – Thong Nguyen: Neighborhood Dynamics in UN Peacekeeping Operations, 1990–2017. International Peace Institute, 11 April 2018.

34UN General Assembly: Summary Study of the Experience Derived from the Establishment and Operation of the United Nations Emergency Force. Report of the Secretary-General, UN Doc. A/3943, October 9, 1958, para. 60.

35 Osterrieder et al. (2015): op. cit. 826.

36 Osterrieder et al. (2015): op. cit. 826.

37 Amani Africa: Briefing on the Situation in Abyei. Amani Africa, 29 September 2022.

38Sudan Tribune: Ethiopia maintains “neutral position” toward Sudan – South Sudan dispute. Sudan Tribune, 19 September 2012.

39Ministry of Information – Press and Audiovisual Department: The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Foreign Affairs and National Security Policy and Strategy. Addis Ababa, November 2002.

40Barry Buzan – Ole Wæver: Regions and Powers. The Structure of International Security. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2003. 229.

41Al Jazeera: South Sudan rebel chief meets President Kiir in Ethiopia. Al Jazeera, 20 June 2018.

42The Mahdists, religious and political movement, which overthrew the Ottoman–Egyptian administration (1821–1885) and ruled Sudan from 1885 until 1898 when they were removed from power by Anglo–Egyptian forces who ruled Sudan until 1956.

43Lovise Aalen: Ethiopian State Support to Insurgency in Southern Sudan from 1962 to 1983: Local, Regional and Global Connections. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 8, no. 4 (2014). 631.

44 Yehudit Ronen: Ethiopia’s Involvement in the Sudanese Civil War: Was It as Significant as Khartoum Claimed? Northeast African Studies, 9, no. 1 (2002). 103–104.

45 Aalen (2014): op. cit. 631.

46Kinfe Abraham: The Horn of Africa: Conflicts and Conflict Mediation in the Greater Horn of Africa. Addis Ababa, EIIPD and HADAD, 2006. 158–159.

47Molla Mengistu: Ethio–Sudanese Relations: 1991–2001. A Thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of Addis Ababa University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations, Addis Ababa University, 2002.

48University of Pennsylvania – African Studies Center: Ethiopia–Sudan: Joint Communiqué. University of Pennsylvania – African Studies Center, 19 November 1999.

49David H. Shinn: Government and Politics. In LaVerle Berry (ed.): Sudan. A Country Study. Washington, D.C., Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, 2015. 281.

50Tesfa-Alem Tekle: Sudan’s Bashir Supports Ethiopia’s Nile Dam Project. Sudan Tribune, 5 April 2012.

s51The Irish Times: Ethiopian PM tries to mediate Sudan’s political crisis after bloodshed. The Irish Times, 7 June 2019.

52John Young: Conflict and Cooperation: Transitions in Modern Ethiopian–Sudanese Relations. HSBA Briefing Paper, May 2020.

53Young (2020): op. cit.

54Young (2020): op. cit.

55Arab News: Sudan demands expulsion of Ethiopians from Abyei UN peacekeeping forces. Arab News, 07 April 2021. 56 Ministry of Information – Press and Audiovisual Department (2002): op. cit.

This Article was first published in Issue 4 of Review of Military Science Journal Volume 15 (2022)

Share

Cyber defense: yet another frontline in Ethiopia’s developmental landscape?

Cyber defense: yet another frontline in Ethiopia’s developmental landscape?

Briefing with INSA’s Cyber-Emergency Response Division (Ethio CERT)

In today’s day and age, cyber capacity has increasingly become a necessary precondition for any country’s global competitiveness; in trade and commerce, technological advancement, intellectual property, and political and social well-being. As such, cyberspace has quickly become one of the top three global security threats in our current highly globalized world. Africa, expecting a population boom in the coming decades is expected to become a target of this security threat by cyber thieves, terrorists, and countries. With the increasing digitization of banking and financial systems, election systems, education, and healthcare systems, multi-billion dollar infrastructure projects, as well as security and intelligence systems- global financial loss and damages make this sector the third largest economy in the world.

In February of this year, INSA reported that more than 2145 cyberattacks were launched at Ethiopia- primarily targeting Ethiopian financial institutions, educational institutions, security and intelligence institutions, medical institution, media establishments, as well as government offices. However, the report does not detail the countries [geographical locations]/ groups/ or entities launching these attacks. Are there identified entities/ groups/ countries responsible for the attacks? Could you name and rank them?

Normally in Cyberspace, every attack has a source from which it originates. One of the raw measures for our assessment is the IP (internet protocol) address to which it can often be traced. Although the originating country may not necessarily be an indicator of the exact source of the attack, due to the use of VPN or other ways of concealing IP addresses, we are able to identify the origin nonetheless. In INSA’s February report, we disclosed that there were over 2,145 attacks launched on Ethiopia’s various sectors, organizations, and public institutions; the recurring IP addresses include countries one would consider superpowers in today’s international arena. There are less oft-considered nations like the Netherlands and the Korean Republic (DPRK) that also make a list. Given that an IP identification does not necessarily implicate a country, a great solution would be to cultivate cooperation- diplomatically or otherwise- with other nations in identifying the attacks (and attackers) from each other’s cyberspace. This is what we have come to call “cyber-diplomacy”; given the lack of physical boundaries for this problem and its global prevalence, mutual cooperation between countries is vital. In this context, if a country is unwilling to cooperate in this matter, that might also be an answer in itself.

Beyond the identification of countries and geographic locations, determining groups/ entities responsible for cyberattacks requires more advanced methods of attribution; here we look beyond the IP address to identify and attribute the attack to a specific threat actor such as an individual, a group, or a state itself. For example, if malware1 was sent, there are routine ways to analyze and reverse-engineer the origin that would reveal details like the timezone or language of the source of the attack. Although much can be done to further analyze such threats, Ethio-Cert as a division, primarily focuses on identifying and monitoring critical assets, and containing threats to these assets.

Going into further attribution might have its own limitations as it requires technological, financial, systems, and manpower capacities.

Entities like the Cyber Horus group, an Egypt-affiliated known entity/ group operating in the open. Helpfully enough, the group announces its own attacks and identifies itself in attacks- or better- announces the attacks it plans to launch. This helps us scout the geo-political and security landscape better. Previously, domestic organizations and institutions were under the impression that INSA is the sole line of defense against cyberattacks, however, it is now clear – for domestic actors- that cyberdefense requires a collective-level effort.

Given that this particular sector is undisclosed, would you say Ethiopian infrastructure projects are also a target of such cyberattacks?

Cyberattacks, or threats thereof, are attempted periodically and in tandem with the reservoir filling period. These could be direct or indirect attacks. Direct attacks are launched at the project (GERD) itself; this might look like disruptions to source/ input factories directly feeding the project. This could also look like attacks on SACDA2 systems: factories, and grids, given that we digitally operate.

A real-world example of this would be the Iranian Natanz Nuclear plant that was attacked, an attack that destroyed the electricity grid of the site, among other disruptions, delaying the project by several years. This is also to say that even the most isolated systems are rarely hidden from cyberattacks. It is also worth noting that the more resourceful an entity, a state- for example, the higher the capacity to use cyber means to its ends. Silently gathering data and information to one’s own end and publicly disclosing the information is another form of this attack.

There was a past instance of cutting electricity supply to entire cities by attacking control systems to power grids- and INSA has responded with the appropriate measures. Though our duty is to proactively defend against cyberattacks, once they do occur, we ensure that the damage is minimized- without such diligence in cyberspace defense- we can certainly say that there is a will to inflict more damage to cause hurdles in the competition of GERD. It is important to note that once the Dam is fully connected and operational, the risk of a cyberattack is exponential. Security is not something to ensure later, at completion, but a crucial concern at this stage. Alongside the construction of the structure and electrical work of the GERD, building a cyberdefense against the project is a crucial aspect that is often neglected.

It is important to note that once the Dam is fully connected and operational, the risk of a cyberattack is exponential. Security is not something to ensure later, at completion, but a crucial concern at this stage.

Indirect attacks on the GERD might look like, attacking websites and government pages; hacking into public websites and defacing them by injecting malicious codes to display the attacker’s messages is yet another trick. We have a past experience where the message stock widespread fear or panic. At the individual level, high-level authorities (influential people) might be victims of phishing ploys- malware or ransomware that might compromise their work. The indirect attacks are often intended to impose a psychological effect. On our end, we have proactive measures in place for addressing these threats. The first SOC: security operations center. We have 24/7 monitoring and proactive defense operations on systems and networks of national assets; like key infrastructure, services and customers, financial institutions, and others. Our real-time proactive defense includes scanning and detecting vulnerabilities. What kinds of gaps exist? Our team checks if the network traffic is healthy, monitors malicious threats from known databases, and builds situational awareness so as to create effective countermeasures.

In June 2020, associated with the first filling of the GERD reservoir, the Cyber Horus group launched a cyberattack on government institutions’ websites within a five-day span. This creates a psychological impact on the population on a highly anticipated national milestone event. Secondly, in a similar timeframe in June of 2021, there was a similar attack on 37,000 computers associated with the second round of filling by the same group. Additionally, in October 2022, we observed similar activity targeting websites of government institutions, for example, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA). Ethio Cert, as a rapid response team, does not move further into determining the extent and severity of these attacks as our focus is detection, containment, and mitigation.

We also receive requests, tips, and reports from sectoral CERT units of national organizations and institutions that enable us to devise a nationwide early warning system. This loops back to the earlier point on building a collective defense system in cyberspace. Although reactive in our response, small businesses, and enterprises also reach out when they are subject to malware and ransomware attacks where we attempt to mitigate the damages and restore lost files.

Given the manifold threats being made against the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) primarily from Egypt, has the Administration aggregated information on the amount and frequency of such cyberattacks on this infrastructure from Egypt?

It is rare for an attacker/actor to overtly launch attacks from a geographic space and make it easy to attribute. However, the easiest way to identify threats originating from Egypt is their own disclosure through official means like their national mainstream media. Though such threats are not acceptable in diplomatic correspondence, the same is true in cyberspace, where Egypt- affiliated groups identify themselves and their activities; like the Cyber Horus group mentioned earlier.

Describe, for a non-technical audience, what constitutes an attack. And relate it to the broader context of the GERD project.

These groups would first conduct a reconnaissance of our systems to craft the payload, i.e. what they will send. They will then “deliver” the attack on a service operator or website. They will then escalate the attack by attempting to get admin access, which, among other actions would allow the exfiltration of data from internal systems and files; though the damage might not be maximal, this data is what would be used for malicious ends like propaganda use.

In general, building a robust cyberdefense encompasses three aspects, which also constitute the key threats: Confidentiality, Integrity, and Availability. Ensuring confidentiality of protected and privileged information and data by mending vulnerabilities; is a key component of our work as the damages from a breach in confidentiality could, at worst, create crises of national proportions.

Integrity has to do with modifications or changes to existing data; for example in the finance sector – if one change’s the name of a bank account holder, or adds zeros to a sum of money- this constitutes a breach of the integrity of data- and results in financial damages and loss of trust. Lastly, availability means a continuous, and uninterrupted, stream of service; As a familiar example, power outages and network loss or degradations (operation at suboptimal levels) mean that availability is compromised. This aspect, availability, should be of utmost concern once the GERD is online and operational. Especially for a country that wishes not only to utilize hydroelectric power from the project but aspires to sell electricity to neighbors in the region; providing uninterrupted service to buyers, availability is of critical importance. We also need to update knowledge and public awareness of these threats that may arise.

In the unfortunate incident that Egypt launches a successful cyberattack against Ethiopian major infrastructure or public institutions, what is INSA’s level of preparedness to fend against an attack, and/or take counteroffensive measures?

The mandate of our particular unit is to reduce the probability of a successful attack and foil a possible attack at the reconnaissance level. Although we do not take offensive measures, our work and mandate is to ensure that a successful attack does not happen.

Our early prevention work includes securing ports, which serve as gateways or doors, to systems of operation, and routinely monitoring threat scans. In the instance of DDos3, malware, and ransomware (attempt to exfiltrate, overload, or crash systems) we take the appropriate action depending on the threat level. Though we prepare for cyberdefense measures in advance, let’s say that a bank has been targeted; the rapid response team is deployed to then identify the threat- then we monitor the threat before responding. If the threat is on a network, systems, or other SCADA- we respond with the appropriate course of action. We then eradicate the threat, much like cleaning an infection. We then attempt to recover lost files and mend damages after which we compile ‘lessons learned’ which help as input to better build our defense for future attack attempts. This might look like adding this new threat to our database to prevent the same breach. This cycles us back to our initial work: preventative defense. In addition to National CERT, there are also sectoral CERT units that perform this work in the finance sector, in national institutions and assets, and in key national infrastructure. INSA is the agency that ensures this level of coordination.

In addition, setting privacy and security standards, and pushing for a legislative framework to protect citizen data is also a priority. Ensuring compliance with data protection protocols is another aspect of the institution’s work. For example, if any bank is to issue VISA cards to customers, they will not only need to comply with PCI DDS4, the industry standard, but also fulfill their obligations to INSAs audit requirements

To follow up on the point about individual-level effort, what safeguards would you recommend to everyday citizens to protect their digital identity?

There are 3 components to cybersecurity: People, Processes, and Technology (PPT). This question relates to the people component of cyberdefense and an aspect that narrows or widens the chances of an information breach. People, be it unknowingly or out of negligence become targets of data theft or breach. This is why public awareness campaigns are crucial. For example, in phishing attacks, people receive email links saying “You’ve won a lottery” or “XYZ has sent you a message on Facebook”; with a prompt click here to open! These messages are often crafted to entice the user based on their internet history. If the email is about a Facebook message, there would be a replicate Facebook page with subtle changes to the URL link; for example zeros in the place of Os to a subtle change that would often be overlooked. When the user attempts to log into the fake URL, the phishers would then steal the login credentials and reroute the user to the original Facebook URL. The user might be surprised to later find that they have been locked out of their account, and discover suspicious activity.

Before logging into any website, especially for URLs shared over email and other mediums, users must always check the link before entering their credentials. The same goes for online banking platforms, users must pay close attention to the URL of their bank’s website before entering their username and pin codes. If one is to receive an email or text that they have received a sum of money, they might immediately click the attached link and hastily enter their user and passcodes, a minor mistake that could jeopardize their finances. To avoid this problem, users must set up multifactor authentication systems on their devices to increase security.

Another safeguard is to always download apps and software from the original source, or a trusted provider. This could be the AppStore for iOs users or the Google Play Store for Android users. In Ethiopia, people often ask their music/ multimedia stores to download music or movies for them- with no knowledge of the source. The same is true for computer applications, like MsOffice and Windows applications, where users will obtain ‘cracked’ software to avoid paying for them. This is yet another common negligent practice that leaves internet users susceptible to the theft of their data. These gaps in awareness can be addressed by public awareness efforts and education.

At the organizational level, companies need the utmost due diligence in their procurement process as they might be vulnerable to supply chain threats for purchasing, en masse, the cheapest possible products (anti-virus software, for example) with no knowledge of the source.

What recommendations does the Administration forward to public sector employees, and regular people, to safeguard the security and privacy of their information?

Although there is much to be done in the protection of private data for individuals, through legislative means and public awareness; state institutions like ours primarily prioritize issues of national security. Due diligence, at the individual level, is important and also requires national-level awareness campaigns on private data protection. INSA does some public awareness activities on our social media channels and websites, through mainstream media channels, TV, and radio. In addition, we host a national cybersecurity awareness month, a month dedicated to building public awareness of cyberspace, and the threats, furnished with various activities for all sectors. Exhibitions, such as the one held this year at the National Science Museum, have an exponential benefit to the field and we hope to continue such engagements with the public in the coming years.

How would Ethio-CERT encourage young scholars to pursue the cybersecurity field?

First, youngsters need to identify their interests and talents. They need to know their hobbies and leanings. If they take a keen interest in coding and programming, there are various open-source learning opportunities online. Family support is also crucial in nurturing and connecting youngsters to the necessary resources to develop their talents. INSA also hosts various events for youngsters and young professionals with knowledge and interest in networking, windows/Linux, and operating systems. In the Capture the Flag (CTF) hacking marathon we hosted in this year’s Cyber Awareness month, we identified over 45 talented youngsters, as young as twelve years old, with a natural talent in the various assessments we offered. INSA has a host of initiatives, like the Ethio-cyber Talent Center (https://www.insa.gov.et/), designed to encourage young minds with an inclination in the field of cybersecurity.

Footnotes:

1 Malware or malicious software, is any program or file that is intentionally disruptive or harmful to a computer, network, or server.

2 SCADA (supervisory control and data acquisition) is a category of software applications for controlling industrial processes, which is the gathering of data in real-time from remote locations in order to control equipment and conditions.

3 Distributed Network Attacks (DDoS) attack takes advantage of the specific capacity limits that apply to any network resources and attempt to overwhelm/ crash systems.

4 The PCI DSS is the global data security standard that any business of any size must adhere to in order to accept payment cards.