TPLF, OLA-Shene, and Al-Shabab: a Tripartite Alliance

TPLF, OLA-Shene, and Al-Shabab: a Tripartite Alliance

Tolera Gudeta Gurmesa

Independent Researcher

Dislcaimer :

The author of this article employed various primary and secondary data sources, as well as personal travels to substantiate their claims. The views expressed in this article do not represent the views of our institution.

Ethiopia’s conflict in the North proved an opportune moment for inauspicious groups existing in enmity to convene against the common goal of a weakened, if not decentralized, Ethiopia. The Oromo Liberation Army (OLA-Shene), an insurgent organization recognized by the Ethiopian government as a terrorist group, brokered the alliance between Tigray People’s Liberation Force (TPLF) and Al-Shabab. This collaboration gives Al- Shabab an entryway to Ethiopian domestic affairs while facilitating TPLF’s agenda of destruction. This article attempts to contextualize the conflict in Ethiopia’s Northern Region, details the parties, as well as elucidates their relationship vis-a-vis each other. It expands on and details the expansion of OLA-Shene and Al-Shabab’s bilateral arrangement to include TPLF, introducing a dangerous security risk across the Horn Region.

Before the launch of an offensive attack on Ethiopia’s Northern military command, the TPLF leadership made extensive preparations for the establishment of an autonomous government of Tigray intending to form a breakaway state. The TPLF, which had previously formed a secret alliance with the OLA-Shene terrorist group, fostered a triple alliance with the Al-Shabab terrorist group under the auspices of the OLA-Shene group and continued its activities to destabilize Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa.

Origin of the conflict

The popular protests, along with other push factors, brought a doomsday to the TPLF-led EPRDF government which was forced to reform itself and facilitate the premiership of Abiy Ahmed. Following the sweeping national reforms in a move to liberalize the nation’s institutions, the political and military leaderships of the TPLF chose to take a systemic retreat to Mekele, the capital of the Tigray region.

The former-acting president of the Tigray region, Dr. Debresion G/Michael, requested ethnic-Tigray parliament members to declare the independent government of Tigray. To control and mitigate the Coronavirus pandemic, the federal government opted to postpone the nation’s upcoming elections. In defiance of this decision, the TPLF leadership held an unconstitutional regional election on September 9, 2020.

Moreover, the post-reform TPL preoccupied with training its regional Special Forces and paramilitary; to regain its past political and economic hegemony, as well as reclaim the disproportionate federal influence it long held. Then, when TPLF was sure that its war preparation was done, it launched an unwary offensive attack in the late hours of November 3rd, 2020, and massacred hundreds of military commanders and members of the army; as well as took thousands of military personnel into custody and as hostages. This incident sparked the worst security crisis in the nation’s recent history. In an interview with the rebel group’s TV channel DW (Dimtse Woyane), Sekuture Getachew, a member of the TPLF central command described their offensive as a preemptive “lightning strike” move. According to his analysis, “TPLF has victoriously completed,” the first phase of a defense that resulted in the death of countless servicemen.

The federal government succumbed to pressure from the international community to provide access and facilitate humanitarian assistance. At the requests of the interim government of Tigray, the federal government declares a unilateral ceasefire; withdrawing all troops from the Tigray region by June 24th, 2021. TPLF, however, took advantage of retreating federal forces in its widespread looting and killing rampage throughout Amhara region, and later, Afar region. Subsequent Ethiopian Human Rights Commission reports have since published the details and extent of TPLF’s destructions in the neighboring Amhara and Afar regions. TPLF has committed widespread human rights and international humanitarian law violations in these two regions.

The reports show that starting from July 2020, Tigray Special Forces and its allied militias have committed unlawful arrests, torture and extra-judicial killing of civilians, rape of women and young girls, as well as intentional damage to public infrastructure. The report also revealed that TPLF fighters also fired artillery into urban areas, dug fortifications, and fired heavy weapons from civilian homes. TPLF also used places of worship as weapons depots and camps. Additionally, on August 5th, 2021, TPLF fighters committed an attack, killing hundreds of internally displaced persons, including a large number of children who took shelter in health facilities and schools in Afar region, Gulina woreda, Galikoma kebele-4. TPLFs path of destruction is aided by sympathetic organizations, both at home and abroad. TPLF has formed a tactical alliance with armed groups at home such as OLA-Shene, Kimani rebel groups, Agaw, Gambella, and Afa rebel groups (surrogates/proxies). It has also established a tactical alliance with the internationally recognized terrorist group, Al-Shabab.

The Trilateral alliance of TPLF, OLA-Shane, and Al-Shabab

For decades, the relationship between TPLF, OLA-Shene, and Al-Shabab, has largely been hostile and antagonistic vis-à-vis one another. Though their history, particularly during the TPLF’s tenure at the head of government, was characterized by enmity these three entities have now forged a seemingly temporary tactical alliance against a common adversary, the federal government of Ethiopia. The pre-established bilateral alliance between OLA-Shene and Al-Shabab has now expanded into a trilateral alliance, with OLA-Shene brokering between TPLF and Al-Shabab. For these groups, the federal government, as well as a strong central government in Ethiopia, is an undesirable outcome. To this end, their collective aim is to synergistically work to undermine the national cohesion and territorial integrity of the Ethiopian state.

A Tactical Alliance: OLA-Shane and TPLF

These designated terrorist groups have established a tactical alliance following the sweeping political reforms in the country intending to forcibly overthrow the government.

Though TPLF continued to dispute the government’s accusation that they are working in collaboration to wreak havoc in all corners of the country, Kumsa Diriba (commander of OLA-Shene) announced in an interview with Associated Press, that the two groups have reached an agreement, as proposed by TPLF. The government of Ethiopia has indicated that the declaration of the alliance between these two terrorist groups was neither new nor surprising.

In line with their mission, these terrorist groups began to carry out coordinated attacks in various parts of the country.

Adhering to the strategy of TPLF’s Commander-in-Chief, General Tadese Worede, OLA-Shene combatants were seen fighting alongside TPLF during the TPLF’s incursion into other regions, particularly in and around Bati and Kemise towns. Their alliance, as it stands, is not only to topple down the federal government but is also seen by the TPLF as a promising avenue for its eventual return to power.

According to TPLF’s calculations, an OLA-Shene coalition at the head of government will pave the way for the eventual succession and subsequent recognition of an independent Tigray. To bring this project to fruition, TPLF gathered seven accompanying agents to sign a superficial agreement in Washington DC. During the ceremony, live broadcasted by Reuters, the handpicked agents vowed to fight alongside TPLF to forcibly topple down the Ethiopian government by any possible means including military warfare.

A Tactical Alliance: OLA-Shane and Al-Shabab

Since 2017, Al-Shabab has been working to establish a viable, strong, and clandestine network aiming to exploit the chaotic political transition and discontents within the Oromo youth in parts of the Oromia region. Meanwhile, OLA-Shene’s operational capability has attracted senior members of Al-Shabab and Ex-Al-itihad members of ethnic Oromo descent to carry out mass recruitment throughout the region. This has led to further technical meetings on the enhancement of common operational understandings between both sides.

In Aug 2021 Al-Shabab’s head of external operation Sheikh Yousuf Aliugas, Ahmed Immam, Shiekh Abdurrahman Ma’alin Sonfur, and Shiekh Ado Dahir commenced a meeting with their OLA-Shene counterparts, namely Liban Jaldessa, Gurracha Jarso, Robba Guyo, Dalecha Yatani, Abdikarim Oumer, Issaqo Halkano as well as Abduba Wario, and discussed the repeated failure of collaboration on recruitment, training and operational alliance besides the mutually planned operation to disrupt the last national election of Ethiopia. Intelligence sources have revealed that since the war broke out in Ethiopia, the relationship between Al-Shabab and OLA-Shene has grown steadily: particularly with Al-Shabab’s arms support for its OLA-Shene counterpart. Intelligence reports have also confirmed that newly recruited OLA-Shene members are taking explosives, weaponry, and intelligence training in Al-Shabab’s facilities in central Somalia.

Additionally, Al-Shabab has facilitated OLA-Shene militants’ exit passage via Northern Kenya, Moyale. Since the 30th of August 2021, about 60 Al-Shabab fighters were deployed around Ethiopian border areas where OLA-Shene militias use as bases. Al-Shabab has left 20 of the 100 OLA-Shene trainees it had been training since the 23rd of August 2021 and 80 of them have been trying to enter Kenya since the 17th of October 2021 via El-Wak to join the group in Marsabit county. These OLA Shene fighters entered Kenya on late night of 19th October 2021, under the leadership of Wariyo Boru12 and Keche Hola Boru13, and by mid-level Al Shabab leaders, including Beshir Mohammed14 and Sheikh Usman Bilow.

This indicates that OLA-Shene is an Al-Shabab affiliate terrorist group whose members have acquired direct support and training from higher Al-Shabab leaders. To reciprocate for the technical and financial often acquired from AL-Shabab, OLA-Shene members advocate for the inculcation of the ideologies of Al-Shabab via social media and other available means. OLA-Shene also gives a cover and facilitates Al-Shabab cells operating in different parts of Oromia, including West Hararge Hirna; East Harge Chelenko; Bale Zone: Ginir, Goba, Malayu, Dolomana, Haro, Dumal, Dolo and Baradimtu; Jima Zone: Shabe Woreda; Borena Zone Moyale; Guji Zone Negelle Borena; West Arsi Zone Shashamane. This is an indication that Al-Shabab is trying to replicate its Muslim-extremism project in Ethiopia and the greater Horn region using OLA-Shene as its Trojan Horse.

The Tactical Alliance between TPLF and Al-Shabab

There is a clear and mutual interest between TPLF and Al-Shabab particularly in experience sharing. Al-Shabab had the interest to gain insurgency experience from TPLF; conversely, TPLF sought knowledge in launching terrorist attacks and other insurgency tactics from Al-Shabab. OLA-Shene has played a paramount role in middling and brokering the two groups. Having fled the central government and retreated to Tigray, TPLF operatives in Sudan initiated contact with Abdullahi Nadir (Clan-Dir) in early October 2020 in Sudan, soon after the group was pushed deeper into central Tigray.

Nadir was a close associate and aide of the former notorious Al-Shabab Amir Ahmed Godene. Abdulahi Nadir later facilitated a meeting between TPLF’s operatives and Al-Shabab members who were in South Sudan under a business pretext. Nadir also managed to contact mid-level Al-Shabab operatives in Kenya to convene a meeting on how to defeat a common enemy. In early August 2021, a meeting commenced in Nairobi (East Leigh area) between three TPLF operatives as well as Al-Shabab mid-level leaders, namely Shiekh Abdi salam Kabaja’el15 and Salad Dere16. According to our primary sources, both parties have agreed to collaborate on technical matters such as sharing guerilla skills, weapons, and facilitation of one another’s operation (if deemed possible) rather than establishing a strategic partnership. Since the two parties adhere to diverging ideological backing. After the Nairobi meeting, consecutive contacts were made between the two sides in Puntland where TPLF elements proposed to provide 15 mortar weapons to target Ethiopian Units of AMISOM troops stationed around Hudur, Baidoa, and Qansahdere areas of South West State. Intelligence sources proved that Al-Shabab has used those 60 mm and 82 mm mortar shells on ENDF units in Somalia.

Part two of the this article will be published in a subsequent edition.

Share

Engaging with external actors regarding the national dialogue process: Writing the rulebook is essential

Engaging with external actors regarding the national dialogue process: Writing the rulebook is essential

Negusu Aklilu

Coordinator of Destiny Ethiopia Initiative

Twitter : @NegusuA

Negusu is a dialogue facilitator who designed and led the facilitation of various high-profile residential consultations including among historians, youth, women, media professionals, activists, religious and cultural leaders, justice professionals, and pre-election dialogues among political parties. He also co-initiated the Multi-stakeholder Initiative for National Dialogue (MIND) initiative which is a consortium of eight local organizations that has laid a foundation for a national dialogue process in Ethiopia. Negusu’s past experiences include complex climate adaptation program management in bilateral and international organizations and policy advocacy in a local environmental NGO. Negusu has initiated and led the Destiny Ethiopia Initiative that conducted a transformative scenario planning process with 50 Ethiopian influential leaders, who drew four scenarios of possible futures for Ethiopia. He has received several national and international recognition for his contributions in the field of environmental and climate change governance, and is a Yale World Fellow.

By profession, Negusu has a combination of expertise in ecology and systematics, environmental diplomacy, and global governance & human security, and dialogue facilitation. Currently, he is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Massachusetts, Boston working on the socio-environmental aspects of China-Africa partnerships. As a passionate Ethiopian intending to transform the nation, Negusu would like to continue to actively participate in promoting peace by championing open dialogue, reconciliation, impartiality, and transparency towards the realization of the Dawn Scenario for Ethiopia.

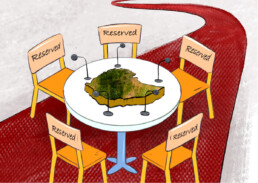

National dialogues cannot happen in a vacuum. There is a host of local, regional, and international actors and factors that have ramifications for the process. No country including Ethiopia would be exceptionally isolated in this regard. Therefore, it is imperative that national dialogue, as a super-sensitive political process, will need to prudently consider the role external actors may play in the process.

Ethiopia launched a National Dialogue Commission about a month ago that is mandated to undertake a national dialogue process in the country. In this regard, it would make a lot of sense to properly understand the interest of external actors in our country in general and in the envisaged national dialogue process in particular.

The role of neighboring countries in influencing and shaping Ethiopian politics has always wavered between two extremes in a continuum of diverse and mixed stances, constructive political and physical support on the one hand and destructive influence through instigating proxy wars and hosting, training, and deploying insurgencies across the country, on the other. We also share people, culture, and history with our adjoining countries. Albeit these are “periphery”, a political metaphor suggesting marginalized communities that are far off from politics centered around the capital. More interestingly, the fates of neighboring countries are unavoidably intertwined, which necessitates conscious effort that stimulates mutual respect and support. National dialogue in Ethiopia, as a process that has the potential to address deep-seated political, economic and contestations in the country, would have an immense potential to effect positive transformation at least in the Horn of Africa.

Any potential support or resistance to this national process by external actors has the potential to affect the degree of success, more so because this has a direct impact on national ownership of the process.

There have also been cases of mutual mistrust and long-standing animosity with some countries in Africa to such an extent that a win by one has been perceived as a loss for the other. For such an actor, the launching of a national dialogue process in Ethiopia might not be good news at all.

While some countries and institutions have officially offered to provide support technically and financially, a host of others are reportedly approaching the National Dialogue Commission directly or indirectly to forge partnerships.

Experience from other countries has a lot to inform our national process. Neither excluding international actors nor giving them the driver’s seat would be helpful, as per literature and experience. Given the varying levels and types of interest from external actors in this national process, though, engagement strategies should acknowledge and respond to such requests in a judicious manner. Any potential support or resistance to this national process by external actors has the potential to affect the degree of success, more so because this has a direct impact on national ownership of the process. The partisanship of external actors is also another major challenge that needs prudent attention.

The kinds of support provided by external actors could be summarized into three categories: political, financial, and technical. External political and development actors could come with a combination of two or more of these broad clusters of support.

The roles of external actors in national dialogue processes range from a heavy-handed approach to a softer one. I will focus on several potential roles for external actors and how we should respond to these requests.

One decisive role is the willingness and capacity to enable or disable a national dialogue, which is key for the legitimacy of the process. In this connection, messages conveyed by all external actors so far have been positive and welcoming. Of course, the importance of this role will continue to be increasingly significant because there might be a need to bring back actors drifting from the process back to a roundtable. Playing such an enabler role by external actors is highly useful for the process.

Funding the dialogue process is also a matter of keen interest to many external actors, be it political or development partners. I don’t see any harm if external actors were able to finance the process for two reasons. First, the process is capital intensive and the economic hiccups our country is facing now might necessitate this support. The second issue is more political than economic. Even if Ethiopia might decide to mobilize its own resources for this process, allowing willing external actors to chip in funds would help in garnering and assuring political support for the process, which is one key factor for the success of the process.

Learning from the experiences of other countries that have conducted national dialogues, though, several cautions need to be taken in this regard to mitigate some likely or inevitable risks. A major political risk is the temptation of powerful actors to dominate the process and influence the outcomes. Public perceptions might also be negatively influenced if this engagement with external actors goes unbridled in such a way that national ownership and hence legitimacy for the process would be eroded. Moreover, the creation of an overcrowded space by competing external actors could create a logistical and administrative nightmare for the Commission in terms of reporting to specific financial templates of donors. In some countries like Yemen, mutually contradictory views have been reflected regarding the process that might cast a shadow as the process moves along. In Libya, external interests directly collided with national interests.

Therefore, any engagement with external actors would be more meaningful if a mutually agreed engagement modality is put in place to govern this partnership. Key elements this engagement modality might need to take into account include ensuring coordination of funding partners, laying out a proper communication protocol for these actors, agreeing on visibility and branding policies, ensuring flexibility of funding arrangements given the sensitivity of this process to a lot of political uncertainties and dynamics, and, perhaps more importantly, a clause on ‘non-interference’. It is imperative that the National Dialogue Commission have a no-branding policy to ensure the friendly support of donors without much ego for visibility.

A major political risk is the temptation of powerful actors to dominate the process and influence the outcomes.

Providing technical support is another area of interest for external political and development actors. Tapping into the vast knowledge and experience in this regard is undoubtedly a wise move. It is evident that financial support pledges by external actors are usually coupled with technical support and sometimes some external actors are overly prescriptive about who should provide the technical support. Therefore, a partnership engagement strategy is necessary for governing relationships with potential technical support providers. Principal risks associated with technical support provision are potential hijacking of the process, and breach of confidentiality resulting from unrestricted access to information flows in the process. In connection with this, it would be useful for the Commission to initially identify areas for technical support so that the partnership would be demand-driven as opposed to supply-driven. Some scrutiny into past track records of technical support-providing institutions might also be helpful to guide decision-making and fine-tune the engagement modality with the actors in question.

When and where local knowledge and experience might be limited, encouraging external actors to forge partnerships with local actors would be very useful to ensure process integrity, customization of methodologies to the local context, knowledge, and skill transfer.

In a nutshell, whether external actors are directly involved in providing financial or technical support, I firmly believe that the communication strategy of the commission needs to incorporate mechanisms to properly and regularly communicate with external actors of strategic importance. This communication strategy could, among others, encompass providing regular information updates on the process, listening to concerns, and communicating recommendations and concerns, particularly regarding these external players. This will enable us to harness the buy-in from the international community.

Another key element is international interest in observing the process. The national dialogue process will pass through phases of varying sensitivity and importance, based on which the Commission might have to decide on when to invite selected external actors to observe various sessions in the dialogue process.

A rule of thumb to national ownership is to nurture trust all along by giving local actors the priority to support the process financially and technically. When and where local knowledge and experience might be limited, encouraging external actors to forge partnerships with local actors would be very useful to ensure process integrity, customization of methodologies to the local context, knowledge, and skill transfer.

Harnessing the political, financial, and technical leverage of external actors is one of the key factors for the success of the national dialogue process. There is a wealth of information and experience from countries that preceded Ethiopia in conducting national dialogue to guide our thinking and decisions. As the purpose of this article is not to provide an in-depth analysis on this matter, diving deeper into these international experiences would undoubtedly help. The bottom line is writing the rule book regarding modalities of engagement with external actors based on lessons from international experience. This will bring the cart to its natural place – exactly behind the horse!

Share

Agreeing the Future: Co-Creating Ethiopia’s Destiny

Agreeing the Future: Co-Creating Ethiopia’s Destiny

Wondwossen Sintayehu

Linkedin : Wondwossen Sintayehu

Wondwossen Sintayehu, is an environmental lawyer involved in a number of biodiversity, climate change, and chemicals laws in Ethiopian and beyond. He was instrumental in coordinating the development of Ethiopia’s Climate Change Strategy, and the recent update to it known as Ethiopia’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). Wondwossen co-initiated the Destiny Ethiopia process, that implemented the Transformative Scenario Planning process creating Ethiopia’s 2040 Scenarios, and its sequel – the Multistakeholder Initiative for National Dialogue (MIND), which laid the basis for an all-inclusive national dialogue process in Ethiopia. Currently, this platform has given way to the establishment of the fully mandated National Dialogue Commission which will hopefully consider the work undertaken by the MIND. Prior to this, he served as a judge at the Federal First Instance Court in Ethiopia presiding over civil and criminal cases. He is currently coordinating a programme known as Justice Transformation Lab, intended to initiate a multistakeholder process meant to transform the justice sector – task implemented by the Ministry of Justice, JLRTI, Destiny Ethiopia together and the Hague Institute for Innovation of Law (https://www.hiil.org/) in the Netherlands. He leads the work for Natural Justice (https://naturaljustice.org/) Ethiopia segment, and is the co-founder of Eco-Justice Ethiopia (https://www.eco-justiceethiopia. org/).

Understanding the Process and Literature behind Destiny Ethiopia’s Initiative for Co-Creating Ethiopia’s Scenarios

December 03, 2019, was marked as one of those rare, hope-filled days for Ethiopians who, over the years, pondered on what holds the future of the country. More than 45 of the country’s prominent and influential figures representing divergent if not opposing views – sat across a vast podium and declared their unanimity and shared vision of a common national destiny.

Together, they charted out four scenarios among which one was endorsed as the most desirable future – for the realization of which they committed to collectively work together. Developed through dialogue amongst a diverse group of thinkers and actors to address Ethiopia’s deep-rooted challenges, the four scenarios predict four possible futures that may unfold in the next 20 years. The first scenario, Dawn expresses an inclusive future where human dignity is valued and cooperation gives access to holistic economic and political growth. The second scenario, characterized by Divided House, demonstrates divisions among regions to administer their territories and pursue their own, separate goals. The third scenario, Broken Chair, explains the government’s desire to meet challenges like unemployment and population growth but is constrained by its inability to effectively govern due to limited resources and lack of capacity. Finally, the fourth scenario, Hegemony, underlines the desire of an authoritarian government to hold power by any means necessary.

What led to the stunning sight of collectively declaring Dawn as a desirable route was a carefully facilitated but veiled interactive process spurred by a convening civic movement commonly referred to as the Destiny Ethiopia Initiative. This article gleans on the Science-Policy interface literature to elucidate what the mechanism of co-production was at play in the Ethiopian context and how this shaped thinking to result in a highly agreed-upon political instrument despite the tense and often unpredictable politico-social landscape.

It examines how knowledge exchange actually happened to inform collective decisions and transform actions. It looks into the methods and processes that helped reshape thinking to result in a shared vision for a common destiny through an unusual collaborative step between people with divergent and often “antagonistic” world views. The article attempts to narrow the apparent loopholes in collaborative knowledge production in science-policy spaces informed by the local experience of “participatory knowledge” creation in a developing country context. In this way, it presents the Destiny Ethiopia Initiative that aimed at spurring a multi-stakeholder, multidisciplinary process where all relevant voices were to be represented within a safe space to inform potential scenarios and pathways into the Ethiopian future.

Through a qualitative method that involved auto-ethnography and interviews, the research questions what the nature of knowledge generation and translation was and inform the mechanisms at play in similar circumstances and platforms.

Exploring the Literature

Science is constantly searching for the truth while politics seeks to win and preserve power in policy spaces often understood to be a heterogeneous, and complex patchwork, where diverse interactions, interrelations, and interdependencies take place (Sokolovska et al. 2019:2). The actors are often several and the nature of their interaction is influenced by a series of cross-scale drivers and complex feedback mechanisms (Norström et al. 2020:182). It is both oversimplified and erroneous to opine policy as barely briefed by specialists from scientific origins since plenty of other players are constitutional to the development of policies (Cartwright et al. 2012 & Cairney 2016). Understanding how several voices are listened to and designing mechanisms to ensure such voices are taken seriously is becoming imperative in the policy-making arena.

The term “knowledge” is broadly construed to mean locally generated know-hows, perceptions, and understandings – more akin to the reference of indigenous or local knowledge in the works of IPBES (Diaz et al 2015). The paper’s usage of the term is thus not directed to knowledge in the sense of expertise emanating from known competencies of epistemic authorities (Lidskog & Sunqvist 2018) but rather idea generators considered to be insightful according to the definition of the initiators of the Destiny Ethiopia process.

The translation of science into policy and practice has acquired great scholarly attention, with the heavy denunciation of the linear model, that presupposes direct and passive use of expert knowledge to inform policies, ignoring the values of circumstantial, normative, and complex processes for shaping policy and practice (Van Kerkhoff et al. 2006 & Pielke 2004, as cited in Wyborn 2015:293). Perceived failures of the linear model are becoming characteristics of the evident divide between science, policy, and practice (Wyborn 2015:293). Instead, collaborative knowledge production (co-production or co-creation) is often conceptualized as a tool for bringing together knowledge generators, policymakers, and end-users with a focus on “civic engagement, power-sharing, intersectional collaboration, processes, relationships, and conflict management” (Wengel et al. 2019: 312). It is considered as an efficient way to move “beyond the ivory tower.” (Greenhalg et al. 2016: 392).

Co-production of truth or knowledge is a pooled contribution of diverse actors and expertise to yield new understandings, intentions, and actions. It is a synergistic process of knowledge generation that includes a variety of disciplines as well as several more sectors of society (Pohl 2008). It has emerged as one essential tool to deal with disparities between science and policy groups (Lemos et al. 2005). Social processes that strengthen co-production take exchanges, coexistence, and collective knowledge production into consideration (Van den Hove 2007:807).

A recent review indicates that conditional cooperation, effective communication, and trust determine the efficacy of collaborative planning.

Hence, it is a collective endeavor where multiple stakeholders from other sectors collaborate for knowledge production (Pohl 2008). The newly generated knowledge is becoming an element of political activity that feeds into political decision-making (Sokolovska et al. 2019:3). However much the benefits of collaboration are understood by society, peoples’ willingness and participation in collaborative efforts are often seriously questioned. The claim that mutual benefit drives societal interest to collaborate has long been contested. A recent review indicates that conditional cooperation, effective communication, and trust determine the efficacy of collaborative planning. Knowledge is not confined within the realm of a few “codified scientific expertise” but rather rests in “every democratic citizen and not specific subpopulations qualified by dint of specialist experience-based knowledge”. And so, co-creative spaces are discovered offering better interaction between two worlds, allowing for the formation of specific policy products while also enhancing the relationship between collaborators which eventually enables them to work and act together. Recently, collaborative knowledge-making is observed to expand into global scientific assessments. The literature is referring to more “participatory knowledge” or “citizen science” particularly at global science-policy platforms (ex: Turnhout et al. 2019: 193).

Legitimacy

The process attained its legitimacy as a result of it being spurred by citizens, rather than the government or other interested parties. This has been amplified by the progenitors of the process that referred to themselves as the convening group, or just the core group of the Destiny Ethiopia process. The group is composed of nine Ethiopian citizens that are concerned about the current state of affairs in Ethiopia. The thirteen individuals (later reduced to nine), initially friends, or friends of friends, represent various worldviews, academic backgrounds, as well as ethnic and religious diversities. As per the coordinator of the group, it is “a microcosm of the fifty individuals selected later as representative of the Ethiopian landscape.” Beyond the setting of selection parameters such as representativeness of political viewpoints, social influence, academic inference, etc. important markers known as “fillers” were also included.

The author, being one of the founders of the Destiny Ethiopia Initiative, conducts the study with the purpose of shedding light on arguments and claims from first-hand information. Thus, combinations of auto-ethnography and other qualitative research tools that comprise focus groups, interviews, and recollection from personal accounts are employed to corroborate arguments with evidence. It discusses how this unique space was created and used to funnel divergent views to assist the collectivity in arriving at a common understanding of Ethiopia’s future scenarios.

A Phased Approach

The Ethiopian Scenario Development process involved three distinct and phased processes – each held at different times, and serving different processes with a common factor that each leads to collaboration among the actors. The Destiny Ethiopia process understood convening as “the vital” component of the Transformative Scenario Planning process.

The conveners at Destiny Ethiopia (including the author of this article followed a staged approach where the first step was the development of a pool list. This is a wish-list of 250 to 300 Ethiopians considered as significantly influential and has some constituencies which they could in turn influence. More than 250 people were identified across the Ethiopian socio-political landscape. The Destiny Ethiopia team then developed a multi-criteria assessment (MCA) to distill and arrive at a mix of 50 influential people for each of which was assigned potential interlocutors among friends and friends of friends.

This was a painstaking process that involved immense debates among the team. This is in spite of the agreement the team had to suspend judgment and be free from personal biases before doing envisaged tasks. The MCA was able to arrive at some level of balanced coverage of people from all walks of life – including parties, civil society, academia, media, and the art world. It also pointed at the need to have proper geographic representation. The other precaution was the maintenance of gender and age balance which the team of conveners took caution. At all times, the convening team made sure that the selected team members were influential, insightful and committed to effecting a change in the system. A couple of observations were made when the final list was agreed to by the Destiny Ethiopia conveners which included: 1) achievement of balance was a painstaking process.

Trust is a rare commodity quintessential for the success of such a high-profile process involving participants with a diverging understanding of the current reality and the future.

The convening process was carefully implemented to attain inclusivity and ensure that entrants can envisage a safe environment where the flow of ideas is unfettered and their voices are represented as uttered by them. An instance of such an assurance was the results of the dialogic interviews which served as a basis of conversation at the first workshop. Each participant was able to notice their specific wordings and historical accounts in the synthesis report presented to spur their initial discussion. The reports carried verbatim quotes from their enrollment interviews administered in advance of their interviews.

Creating a safe space for scenario construction

One significant aspect of the co-creative process was the creation of a safe space for participants to engage in dialogues. Trust is a rare commodity quintessential for the success of such a high-profile process involving participants with a diverging understanding of the current reality and the future. One of the measures that needed to be considered as the requirement of making it a clandestine operation. This is counterintuitive to other SPI processes, which need to embrace transparency and process exposition from the outset. Aside from the apparent safety it creates, some participants are noted to be attracted by the absolute secrecy of the workshops they are invited to pass through.

Establishing a safe space that can be trusted for uninhibited exchange of views by the participants rather than a platform for value-blind multiculturalism (Meseret et al. 2018), thus required meticulous facilitation that nurtures and propagates trust about the process amongst the scenario team members. In such spaces, scenario team members engage in their collective quest for creating meaning for current problems.

One of the principles enshrined and repeated throughout the six months process was what was known as the “Democracy of Time.” This is intended to bring the perception of equality among participants thereby perceived hierarchy lines among them. This was important as some of the members were veteran politicians that have been in leadership, were imprisoned, or exiled for long years as a result of espousing viewpoints inconsistent with the ruling government. While others in the ST grouping were young activists, artists, or media people that may be intimidated to be placed on equal platforms with politicians. Hierarchies or perceptions thereof is thought to inhibit free exchange of ideas and was needed to be dealt with at the very start.

There was a need to level the playing field for all and the notion of “democracy of time” played its own role in the creation of a “safe space” for each entrant realizing all rules work for everyone. To ensure the democracy of time, the facilitators apportioned equal slots of time to make interventions. Before interventions, participants would be told the amount of time allotted for the specific sessions. At the lapse of the allotted time against a speaker, the facilitator rings a handbell, and the speaker stops, even if it was in the middle of an unfinished thought, thereby showing that discipline is more important than the message. At the end of the process one participant reflected on this:

Ethiopia’s politics is marked by the conception that the politician knows for the people, and that [he] has the mandate to speak for and on behalf of the people. Politicians barely listen to the people. Most times we should listen rather than blabber about things we know and things we don’t know. We have learned [through the Destiny Ethiopia process] the discipline of economizing our speech and abiding by rules of discipline.

A major opposition party representative later indicated that this knowledge has been translated into a party disciplining technique. Their party deliberations are now “perfectly timed” where non-adherence is penalized by fines.

Story Telling Sessions

One expression of a safe space for dialogue is the creation of a space for deep, informal, personal conversations. In facilitated processes, story sessions allow participants to co-create and build common narratives (Bojer 2021). Through the Destiny Ethiopia process, these spaces were named “storytelling sessions’’– informal set-ups typically held after dinners, with participants surrounding lit candles and a room filled with an aroma of freshly brewed coffee in the traditional Ethiopian Coffee ceremony style. Here group conversations take place where everyone has to listen to a single person that has a story to share. Pacesetters are encouraged and confirmed in advance of the gathering. The informality of the sessions would lead the participants to dig deep into their most intimate stories and share them with the audience in a collegial spirit that would crack the hearts of the audience. Largely hinged on personal accounts of the participants, the stories being shared often do not relate to thematic issues raised during the formal sessions of the meetings, apparently nurturing familiarity among and trust among participants.

Sustaining Integrity

In-group dynamics, it is important but seems difficult to sustain mutually respectful behavior; which did not prove difficult to attain in our case. This is what happened in the transformative scenario planning process in Ethiopia when it came to abiding by the rule of keeping process confidentiality until a certain fixed date. A verbal agreement was reached among participants in an effort not to divulge information about the process until the launch date. The agreement entered into during the commencement in May 2019 was still standing and respected until the launch in December 2019. While honoring such ‘loose’ agreements is not atypical, such a high degree of discipline is quite uncommon given the fact that some of the participants are social media activists, bloggers, and media house owners.

Part two of this article, which discusses scenario building, knowledge integration process, and outcome preview will be

published in subsequent editions.

REFERENCES

Cairney, P. (2016). The Science of Policymaking. In The Politics of Evidence-Based Policy Making (pp. 1-12). Palgrave Pivot, London.

Cartwright, N., & Hardie, J. (2012). Evidence-based policy: A practical guide to doing it better. Oxford University Press.

Díaz, S., Demissew, S., Carabias, J., Joly, C., Lonsdale, M., Ash, N., … & Zlatanova, D. (2015). The IPBES Conceptual Framework—connecting nature and people. Current opinion in environmental sustainability, 14, 1-16.

Greenhalgh, T., Jackson, C., Shaw, S., & Janamian, T. (2016). Achieving research impact through co-creation in community-based health services: literature review and case study. The Milbank Quarterly, 94(2), 392-429.

Lemos, M. C., & Morehouse, B. J. (2005). The co-production of science and policy in integrated climate assessments. Global environmental change, 15(1), 57-68.

Lidskog, R., & Sundqvist, G. (2018). Environmental expertise. In Environment and Society (pp. 167-186). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

Norström, A. V., Cvitanovic, C., Löf, M. F., West, S., Wyborn, C.,Balvanera, P., … & Österblom, H. (2020). Principles for knowledge co-production in sustainability research. Nature Sustainability, 3(3), 182-190.

Pielke Jr, R. A. (2004). When scientists politicize science: making sense of controversy over The Skeptical Environmentalist. Environmental Science & Policy, 7(5), 405-417.

Pohl, C. (2008). From science to policy through

transdisciplinary research. Environmental science & policy, 11(1), 46-53.

Sokolovska, N., Fecher, B., & Wagner, G. G. (2019). Communication on the science-policy interface: an overview of conceptual models. Publications, 7(4), 64.

Turnhout, E., Tuinstra, W., & Halffman, W. (2019). Environmental expertise: connecting science, policy, and society. Cambridge University Press.Van den Hove, S. (2007). A rationale for science-policy interfaces. Futures, 39(7), 807-826.

Van Kerkhoff, L., & Szlezák, N. (2006). Linking local knowledge with global action: examining the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria through a knowledge system lens. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 84, 629-635.

Wyborn, C. A. (2015). Connecting knowledge with action through productive capacities: adaptive governance and connectivity conservation. Ecology and Society, 20(1).

Wengel, Y., McIntosh, A., & Cockburn-Wootten, C. (2019). Co-creating knowledge in tourism research using the Ketso method. Tourism Recreation Research, 44(3), 311-322.

Share

Light-Up Africa: Transitioning to Efficient LEDs Presents an Opportunity for Green Economic Growth

Light-Up Africa

Transitioning to Efficient LEDs Presents an Opportunity for Green Economic Growth

Dr. Oludayo Dada and

Dr. Wondwossen Sintayehu

Dr. Oludayo Dada (Ph.D.)

Dr. Oludayo Olusegun Dada has over 34 years of professional experience spanning various gamuts of environmental protection; some of which are environmental policy analysis, environmental pollution control, environmental impact assessment, environmental agreement negotiations, and resource mobilization. He led Nigerian and African delegations to several multilateral environmental workshops, negotiations, and conferences around the world.

He has also chaired many global and regional technical committees and actively participated in the preparation of several international, regional, and national technical documents on environmental issues. He served as Advisor and Consultant to International and Regional Organizations like UNEP, UNIDO, African Union Commission, and Africa Institute.

Currently, Dr. Dada is CEO of Newport Technologies Ltd/Abuja, Nigeria. A company that specializes in project conceptualization, design, planning, and management in infrastructural development and environmental matters.

Dr. Wondwossen Sintayehu (Ph.D.)

Wondwossen Sintayehu, is an environmental lawyer involved in a number of climate change, biodiversity, and chemicals management in Ethiopia and beyond. He was instrumental in coordinating the development of Ethiopia’s Climate Change Strategy, and the recent update to it known as Ethiopia’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). Currently, he is the Technical Coordinator for SouthSouthNorth, a Cape Town-based not-for-profit organization, overseeing a number of projects on climate policy, low carbon transport, Recalculation of Ethiopia’s Grid Emission Factor to enable the country to make use of Article 6 projects.

Wondwossen served as Director of Environmental Law and Policy at the Federal Environmental Protection Authority, with the responsibility, among others, of overseeing the development of laws, strategies, and policies on a range of environmental subjects including climate change and carbon markets.

He has represented the country in climate change negotiations and has served as Africa’s negotiator for the Minamata Convention and the Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM).

Wondwossen currently serves as Policy Advisor to the African Group of Negotiators relating to the ongoing chemicals and waste negotiations under the auspices of the Basel, Rotterdam, and Stockholm Conventions and is currently finalizing his Ph.D. in Global Governance and Human Security from the University of Massachusetts, Boston.

A collective shift towards African green economy initiatives

As climate change and rising energy demands destabilize communities, governments around the world are pursuing policies to support the transition to green economies. Across sub-Saharan Africa, from South Africa to Nigeria, ministries are implementing short to medium terms plans to ensure future stability and prosperity in a changing climate and uncertain energy future.

The green economic transition also presents a unique opportunity for new, clean energy and technology industries. A critical component of the clean energy-based economy is the transition to energy-efficient LED lighting technologies. As African governments develop national plans to accelerate access to clean energy and mitigate the effects of climate change, local manufacturing of LEDs could stimulate local economic growth, generate jobs, and safeguard consumers from inefficient, toxic lighting products.

Governments across Africa are rejecting toxic fluorescent lighting and leading the global transition to energy-efficient, mercury-free lighting products. In May, representatives from Africa proposed an amendment to the Minamata Convention on Mercury to eliminate special exemptions for mercury in lighting. If adopted, the amendment would safeguard public health, ease the energy burden on increasingly strained national grids, and stimulate local economic growth.

Phasing-Out Mercury in Lighting

A decade ago, fluorescent lights were viewed as an energy-efficient alternative to less-efficient incandescent and halogen lights, and risks associated with mercury in each bulb were tolerated as a necessary trade-off for the efficiency benefits. Today, thanks to major advances in light-emitting diode (LED) technology, LED lights are a cost-effective, safe alternative that can replace fluorescents in virtually all applications.

“The technological advancements in lighting over the past decade have far surpassed even the most advanced mercury-containing fluorescent bulbs,” explains Shuji Nakamura, Nobel Prize for Physics (2014) and Inventor of the blue light LED.

“My work on blue LEDs enabled innovative bright and energy-saving lighting products to reach markets across the globe. With the proposed amendment to the Minamata Convention and implementation of national-level regulations to phase-out fluorescent lighting by 2025, countries can accelerate the transition to LED lighting technology to benefit people and the planet.”

As governments in wealthier countries like the European Union and the United States phase out mercury lighting products, unregulated and under-regulated markets, primarily in Africa, are at risk of becoming dumping grounds for low-quality, inefficient fluorescent lighting products. Without government action, African consumers will be left with dangerous, energy-intensive lighting options.

Proper disposal of end-of-life mercury bulbs remains the main concern in African countries. A recent report found that the collected and properly recycled e-waste (not just lighting products) was at 4% in Southern Africa, 1.3% in Eastern Africa, and close to 0% in other regions. Most bulbs are disposed of with general waste, where due to their fragility, the bulbs easily break and disperse mercury vapor into the environment. Mercury released from broken bulbs can travel hundreds of kilometers, then are deposited into land or water sources—contaminating vulnerable communities along the way. The mercury may then be converted into a bio-available methylated form, which then enters the food chain.

LEDs remove the unnecessary risk of exposure to toxic mercury vapors for people and workers when light bulbs break in homes, offices, schools, and businesses. They also reduce the amount of mercury contamination at landfills and waste sites by cutting the risk of hazardous waste at the source.

LEDs Present a Business Opportunity in Africa

The transition to clean LED lighting is possible in the short term in Africa because all countries are importers of fluorescent lighting. With no local production of fluorescent lighting, there will be little impact on local jobs, on the contrary, there is an opportunity for localized production.

LED lamp assembly offers an excellent opportunity for local businesses and entrepreneurs to establish new operations in the assembly and manufacturing of LED lighting products. Significant production is already taking place in East, Southern, and West Africa to supply national markets and export to neighboring countries. With synchronized lighting regulations and investment in new LED businesses across the continent, Africa can supply its growing demand for energy-efficient lighting products.

In Zambia, for example, Savenda Electrical employs approximately 30 people in the manufacturing of general service lamps, as well as street lights and off-grid solar products. The lamp assembly is taking place in an industrial park outside of Lusaka.

In Rwanda, Sahasra Group invested $3 million in a state-of-the-art LED manufacturing facility in Kigali Prime Economic Zone.

The Rwanda Development Board called the business a ‘strategic investment,’ as Sahasra aims to support Rwanda in transforming its energy landscape by creating jobs, accelerating the transition to energy-efficient lighting, and enabling the lighting market to become self-sufficient. Local manufacturing also allows import substitution, generates exports, and gives impetus to locally made and sourced African products.

Global Efforts to Eliminate Mercury in Lighting

Earlier this year, 36 African countries proposed an amendment to phase out the most common types of fluorescent lighting under the Minamata Convention. If adopted at the upcoming Convention of Parties (COP4), the amendment would lead to a global phase-out of most fluorescent lighting products by 2025, resulting in massive cost savings, reductions in mercury pollution, and cuts in global electricity consumption by up to 3 percent.

Accelerating the transition to LEDs in Africa also presents an opportunity to alleviate the energy burden on increasingly strained national grids. Rolling blackouts and energy shortages have come to characterize electrification across Africa. Because leading LED technologies to consume about half as much energy as mercury-laden fluorescent alternatives, transitioning markets to LED would reduce energy costs from the household to the country level.

In contrast, governments who drag their feet on this issue will experience significant economic losses. In the EU, an estimated €5.5 billion is lost each year the European Commission fails to act on a mercury-based lighting ban.

What are the Next Steps?

By leading this global transition, African governments are signaling that it is time to stop using the continent as a dumping ground for the world’s hazardous fluorescent lighting products. LED lighting technologies will only become more energy-efficient over the following decades, but policy measures must support technology advances. A wave of policy action, starting with the proposed amendment, and supported by Minimum Energy Performance standards (MEPs) in the lighting sector, will stimulate local LED industry growth and respond to consumer demand for higher-quality products.

Share

It’s Time for an African People’s Tribunal: It’s Time for Ethiopia to Put the U.S., the UN, and the TPLF On Trial.

Mesfin

Jeff Pearce

Historian, novelist

Twitter : @jeffpropulsion

A few days ago, I stood in what felt like the frozen still image of a cyclone, the appalling destruction that TPLF marauders committed on the police station and on the administration offices of Lalibela. You can see it for yourself in the shots taken by photojournalist Jemal Countess, who traveled there with me, and in my own video report. At the time, a very angry police officer told one of our team, “I blame America for this!”

And he wasn’t wrong. It is incredibly condescending at this point to believe that ordinary Ethiopians would be taken in by a “propaganda campaign” on the part of the Abiy government or by #NoMore activists who criticize the Biden administration and the UN for its shameless backing of the TPLF. And it’s quite revealing that those on the other side are quick to marginalize a growing Pan-African movement, trying to smear it as a put-up job by the government. Trust me, Ethiopians can make up their own minds just fine, and their animosity towards Western authorities, Western media, and Western arrogance has its own real foundation.

But where can they air their grievances aside from their own media at home? There have been a few recent cracks in the monolithic wall, but by and large, TV networks and papers in the U.S. and Europe shut them out and rely on the same old apologists for the TPLF, such as Alex de Waal, Martin Plaut, William Davison and others.

Even as the TPLF scurries back to its regional enclave, blatantly lying about its military reversals and claiming that it wants to give peace a chance, its propaganda machine still pushes the Tigray Genocide narrative, despite it being debunked by the joint investigation of the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights and the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission. Have to give the terrorist group its props, its lobbyist has relentlessly pushed the most sinister, downright evil items to try to hobble a democratic African government.

The TPLF have been desperate to get Abiy in the dock at the International Criminal Court for some time, its thugs even barging into UN offices to try to get the names of sexual assault victims and the locations of safe houses, as I first reported months ago. It is not enough for them to have virtually the entire Western media in its pocket, it desperately wants this stamp of validation from The Hague.

So maybe it’s about time pro-Ethiopia activists flipped the table — and got their own tribunal. Let me explain what I mean, as I am not talking about a judicial process through the Ethiopian state and its courts. That time will come, and that process needs its day. No, I want to borrow a different idea.

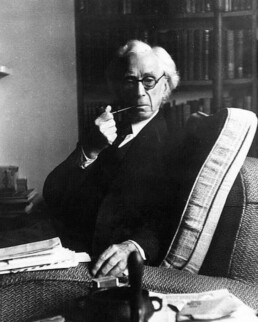

For those who have never heard of Bertrand Russell, he was a tweedy, softspoken but fiercely intelligent activist and philosopher who was still plunking himself down on air-cushions for sit-in protests in Trafalgar Square when he was in his nineties. And in 1967, he organized what came to be known as the “Russell Tribunals” — a kind of activist “do it yourself” set of panels that judged whether the U.S. had committed war crimes during the Vietnam War (spoiler alert; did they ever).

The tribunals had no legal authority or power. They were, when you get down to it, a very elaborate PR stunt to change the dominant thinking over Vietnam, and the spotlight for them relied heavily on the reputations of their distinguished members, which included among others Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Tariq Ali, James Baldwin, Alice Walker and Stokely Carmichael. But they made a difference.

As Cody Foster put it in a 2017 article looking back on the initiative, “The tribunal and the marches did not bring the war to a close, but they helped energize international opposition to colonialism and imperialism.” In Russell’s mind, “the people — properly organized and motivated — could hold governments in check. It was an urgent idea in 1967; it remains one today.”

Indeed, it does. Especially when as a friend of mine, an Ethiopian journalist, reminded me only yesterday, Africa is being coerced relentlessly to accept the Western world’s version of justice.

But why should it? As I’ve asked many times, why should Ethiopia or the rest of Africa automatically genuflect and defer to those who appoint themselves the arbiters of morality from their comfortable perches in America and Europe?

It’s time for an African People’s Tribunal. A tribunal in which Ethiopian voices

are properly heard. One with seats for eminent African figures in law, literature, Pan-African activism, science, economics, etc.

Like the Vietnam tribunals of decades ago, it would lay out the case against the TPLF, as well as U.S., UN and EU complicity in helping a terrorist group destabilize a nation in the Horn of Africa — one which marked one of the freest and most open democratic elections in the continent’s history.

You can rest assured there will be no shortage of evidence. From the scores of soldier witnesses who endured the attacks on the five Northern Command

outposts to the survivors of the Mai Kadra Massacre to the evidence emerging of at least 32 women raped at Ayna Eyesus and the vengeful destruction in Lalibela, Dessie and so many other locales, there will be much to keep the tribunal busy.

I personally believe we need such a tribunal — and soon. In a brilliant article written by Bronwyn Bruton and Ann Fitz-Gerald, the case is made for TPLF leaders who planned and initiated the war to give themselves up, while suggesting that Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy “declare amnesty for the TPLF rank and file who were coerced into fighting…”

This idea needs strong support in public forums, and if it can get some traction, it would encourage those same rank and file to step forward as tribunal witnesses.

The West needs to finally comprehend that most Tigrayans were not victims of the Ethiopian government in this conflict, but of the TPLF, who didn’t hesitate to extort and threaten them to give up their meager supplies of food and to turn over their children to fight.

The West needs to finally comprehend that most Tigrayans were not victims of the Ethiopian government in this conflict, but of the TPLF, who didn’t hesitate to extort and threaten them to give up their meager supplies of food and to turn over their children to fight.

Who would organize these tribunals? Who would run them? And where? My suggestion would be to hand this idea off to the good folks in the #NoMore movement, but it needn’t be dumped on the plate of the top organizers in America. Like Black Lives Matter, #NoMore seems to be mushrooming and evolving into a loose franchise network, allowing other activists around the globe to bring what they have to the table. This is smart — and it means a Pan-African renaissance can flourish and grow according to its needs.

So, how about it, African activists? Do you want to take this ball and run with it? Find the writers, statesmen and stateswomen, and great thinkers on the continent who would be willing to be members?

I can assure you that once you do, there will be a long line of reporters, photographers, witnesses, and survivors queuing up to present the evidence.

As for where to hold the hearings… One spot could be Nairobi, a choice that has a certain dark humor irony to it since so many major news outlets still think they can get away with filing stories on Ethiopia from there. Will the Western media want to cover the tribunals? Of course not!

You can practically draft in your head the passive-aggressive dismissal that the Great Fungus of Crisis Group, William Davison, will come out with when he festers anew on BBC. Or TRT. Or France 24. This is a guy who doesn’t think twice about trying to smear #NoMore as a shill for the Abiy government.

So no, don’t expect to see any CNN cameras or Cara Anna of Associated Press showing up to cover the African People’s Tribunal if it comes into being. And that’s just fine.

Instead, the tribunals’ organizers should look to RT, sympathetic Turkish media, more receptive media outlets in Europe, South America, and Far East Asia who will do a proper or at least reasonable job of covering the presentation of evidence.

If the various foreign policy debacles of the United States in the last 60 years have taught us anything, it is that — like the colonial empire of Britain — it can only endure so much shame and so much loss of prestige.

The U.S. government is happy to get into bed with truly evil people — but it doesn’t like others knowing about it.

As someone who now has to accept that he’s become an activist, I think we’ve wasted far too much time chasing attention on Western media outlets, which we hope in turn will lead to a sympathetic hearing in the corridors of power in Washington, London, Brussels, Ottawa and elsewhere.

As someone who now has to accept that he’s become an activist, I think we’ve wasted far too much time chasing attention on Western media outlets, which we hope in turn will lead to a sympathetic hearing in the corridors of power in Washington, London, Brussels, Ottawa and elsewhere. Folks, it might never happen… or if it does happen it might be too late.

I would rather leverage other media against those news outlets who have proven again and again that they are openly hostile against the truth.

All this time, we’ve been forum shopping along the same strip of real estate. We

can go elsewhere and do better.

And I can tell you after writing professionally for 40 years — a reasonable chunk of them for national magazines, newspapers at home and abroad, and network television — that nothing angers the major media brands like being shut out of a story (case in point, the Grand Dame of Entitlement herself, Nima Elbagir, clearly fuming that she can’t stroll back into Ethiopia after repeatedly labeling a country).

The big media outlets will react poorly if they can’t push their way in while day passes to the tribunal hearings are given to this or that Brazilian newspaper or to China’s CCTV.

When finally let into the hearings, they may still attempt their corrosive spin, but they’ll be outnumbered and contradicted by the rest of the world’s media, which — with luck — will build new momentum.

Half of this tragic conflict has been spent on the battlefield of public opinion in the West, trying to convince certain powers that be they should stop supporting a group of homicidal psychopaths. And part of that mission has always been to gain renewed respect for African voices.

But that respect won’t come until those voices are amplified, until the mechanisms for helping to decide world opinion are in African hands. And one of those mechanisms can be created now if there are activists ready to act on this vision and bring it to life.

But that respect won’t come until those voices are amplified, until the mechanisms for helping to decide world opinion are in African hands. And one of those mechanisms can be created now if there are activists ready to act on this vision and bring it to life.

Share

My Dam, My Why, My Dignity

Mesfin

Mekdelawit Messay

PhD Candidate

Florida International University

Twitter : @Mekdi_Messay

Why does Africa’s forerunner project, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) inspire, motivate and enamor its supporters so much? What is it about the GERD that resonates with us, moves us so deeply that we give from the little that we have, stand by it with our heads held high in the face of fierce powers, and show it a loyalty so deep it even inspires others to stand with us? In his book called Start With Why Simon Sinek says, “people don’t buy what you do, they buy why you do it.” He argues that starting with the “why” of doing things, then moving on to “how” and then to “what” makes for lasting successful endeavors. He calls this approach “the golden circle.” Sinek’s book is written in the context of business and how people who lead with “why” can inspire others, but this core principle of starting with “why” can also be extended to all aspects of life.

I have found striking parallels and application of this principle in the case of the GERD; in the unrelenting will of the people to see it through, in the unparalleled support it has amassed, and in the fierce conviction it has inspired. For me, and for many people, constructing this dam and providing electricity to every Ethiopian comes down to ensuring a dignified life for all. The desire for dignity, a dignified life, a dignified country, a dignified present and future lies at the heart of Ethiopia’s endeavour. This is the “why” behind the GERD and it is this drive

The desire for dignity, a dignified life, a dignified country, a dignified present and future lies at the heart of Ethiopia’s endeavour.

which inherently resonates with me and many others, that compels us to give our unwavering support for GERD.

According to Sinek, after crystallizing our “why”, the next step is to examine the “how” of operationalizing our “why.” How can Ethiopia ensure a dignified life for all? The way to Ethiopia`s “why,” the way to a dignified life, is through the utilization of available resources. Ethiopia is endowed with seasonal rivers, abundant land, immense hydropower and irrigation potential and a large youth demographic that can drive the country forward. Utilizing all of these resources that the country is endowed with to the best of its abilities – that is Ethiopia`s way of achieving its “why”, that is our “how.”

The final step is identifying the “what” – the proof and manifestation of our “why,” as Simon Sinek puts it. The GERD now makes perfect sense. The GERD is the emblem of Ethiopia`s will to reclaim its dignity, to go against all odds to provide Ethiopians with a decent life today, and to gift the generations to come with a better and dignified Ethiopia. It is a physical manifestation of Ethiopia`s “why.”

As emphasized by Sinek “people don’t buy what you do, they buy why you do it” and the reason why Ethiopia is building the GERD, is a universal concept; to provide a dignified life for all! It is this inherent alignment and resonance with the “why” behind the GERD that inspires and brings millions to rally under the banner of GERD. Intrinsically, we can all relate to this yearning for a dignified life; because that is what everyone is trying to achieve, one way or another, day in, day out, be it in our jobs, education, how we raise our kids or govern communities. It is because

The provision of clean and affordable energy will have far reaching effects beyond provision of light, in terms of food, water and energy security, improved education and health care access, better climate change action and environmental conservation, improvement in quality of life, expansion of industries and the resulting boom in job opportunities and innovation.

Ethiopians, at the core of our being, sense an aligning with the “why” of the GERD, that is why people from all walks of life wholeheartedly support it, come rain or shine.

The GERD is a flagship project of monumental scale which will transform the lives of millions of Ethiopians and contribute to the goal of ensuring an honorable life to every citizen. I have highlighted in multiple forums how the provision of clean, affordable, and abundant energy will have ripple effects in multiple facets of individual lives, communities, our country, the Nile basin region, Africa and even in the world. Millions in Ethiopia are still living in the

dark with no access to clean water, education, health care and other basic necessities. This constitutes a serious lack of basic human rights and is tantamount to living as the medieval ages in the 21st century. The provision of clean and affordable energy will have far reaching effects beyond provision of light, in terms of food, water and energy security, improved education and health care access, better climate change action and environmental conservation, improvement in quality of life, expansion of industries and the resulting boom in job opportunities and innovation. The GERD, as a mega structure built on transboundary water, will also foster regional collaboration and integration, spreading its benefits beyond Ethiopia to neighboring countries. It will also play a significant role in pushing Ethiopia and neighboring countries in the direction of achieving the UN sustainable development goals (SDGs).

Sinek elaborates on the power of alignment with the “why” of things in his book, giving the Apple brand as an example. He writes about people who align with the “why” of Apple, who wait in line for hours to get their hands on the latest Apple product, and are even willing to pay a premium for it even though there are other products with better features and pricing. Similarly, Ethiopians align with the “why” of the GERD are happily paying a “premium” out of the little they have, which is a great show of their commitment. Sinek identifies such people aligning with the values, the “why” of a company as loyalists; and indeed Ethiopians are loyal to their country and to the GERD. They align with the “why” behind the GERD because it is a just and honorable endeavour! It is for a dignified life!

Sinek further talks about what happens when enough people believe in what we believe causing what he calls a “tipping point.” Others refer to this concept as the formation of a “critical mass” or “the point of no return” to mean the same thing – a threshold after which change is inevitable. The GERD has not only galvanized and enamored Ethiopians, but the whole of Africa. It is easy to see why the inherent drive to ensure a dignified life would resonate with Africans. The GERD is the embodiment of the spirit of “Yes we can!” It speaks to Africa’s audacity and aspiration to reclaim its dignity, destiny and future. It represents Africa’s renaissance, a step forward in the process of transforming Africa through the generation of a much-needed energy. No wonder people who have been historically treated less than human, told that they can’t, that they are not equal to the rest of the world or worthy of basic human dignity would resonate with this riveting outlook! It is because millions of fellow Africans resonate with our “why” that they stand in solidarity with Ethiopia. This is why we see a tipping point forming. As Sinek notes, when enough people believe in what you believe, a tipping point develops and tips the scales, causing the status quo to change. A

tipping point in the Nile basin has already been reached. The talk of equitable and reasonable use is more prevalent and forceful now than at any time in our history, not just at the higher levels of governance and leadership, but also at the level of everyday individuals, Ethiopians, and Africans. This is the recipe for revolutions, for radical changes, a critical mass of people driven by the same why. Change is coming!

Share

Jeff Pearce’s Brief Reflection on His Visit to Ethiopia

Mesfin

Jeff Pearce sat down with Horn Review to discuss his brief

trip to Ethiopia and highlight his general observation of the

situation on the ground, including recently liberated towns

in Northern Ethiopia.

I would first have to say that I have received the warmest welcome from Ethiopians everywhere I have visited. Ethiopia is a country that is quite near and dear to my heart, and I am always grateful that the people are appreciative of my advocacy. It is something that I do not take for granted. However, I am always cautious not to appear as though I am speaking for the Ethiopian People because I know that the time will come when this costly war will be over and there will be peace.

This will be a time for people like me to keep quiet so Ethiopians will have to decide how to move forward. I generally avoid passing value judgment about the intraregional politics of Ethiopia. I feel that my role is clear. For this reason, I am conscious of the proper limits of my advocacy and I take this opportunity to encourage Ethiopia’s youth to be active participants in this process; I say pick up the baton and continue to fight on because the battle is not easily won. The fight for autonomy and self-determination will undoubtedly spread to other African countries passing through similar struggles against the West, among others.

African officials and experts are often denied visas to attend international conferences. Yet, instigators, in the guise of journalists, go to war fronts and produce highly partisan propaganda. There is an embedded sense of entitlement in the west, Europe, and the UN, that Africans are having to fight off. For example, in most mainstream reporting for Ethiopia’s conflict, there is often a small reference to how “TPLF brutally administered the country” without ever relating it to the conflict or the current sentiment of the Ethiopian people towards the TPLF; which amounts to, at the very least, omission. As someone who has researched Ethiopia for nearly a decade, it is clear to me that the reports pushed out by the mainstream media lack the contextual backing and nuance that history books offer.

My visit to TPLF occupied towns has confirmed my fears about the scale and extent of the

destruction. I have had discussions with heads of espionage operations, gang members, and members of organized crime groups, and I can say that the level of brutality and sociopathic brilliance I have witnessed from TPLF victims is unmatched -but with the TPLF it looks as though their sole approach seems to be getting others killed until they get what they want.

TPLF, in its heyday, ran Afar’s entire salt mining industry through heavy exploitation of the local population. We see the same pattern in the way they administered the nation’s tourism industry from Mekelle. It is quite unfortunate that the plight of the Afar people continues in the form of overt violence today.

We are told that Ethiopia received 30 Billion dollars in aid during its stay in power, yet there is little to show for it besides the fact that children and relatives of TPLF members live lavishly in North America and Europe, and attend exclusive universities. The TPLF has plundered Ethiopia’s wealth into foreign real estate investments, and heafty international shareholdings, among other things.