Ethiopia's Green Legacy and Great Green Wall Initiative: Comprehensive Responses to the Environmental Challenges in Africa

Ethiopia's Green Legacy and Great Green Wall Initiative: Comprehensive Responses to the Environmental Challenges in Africa

By Silabat Manaye

Silabat Manaye is international relations professional based in Addis Ababa. His research interests include water politics, geopolitics in the Horn of Africa, and War Journalism. He authored two books on Nile geopolitics. His MA thesis focused on Ethiopia’s Environmental Diplomacy in the Case of the Nile River.

The Impacts of Climate Change in Africa

According to the IPCC report (2023), the impacts of climate change on developing countries in

Africa, one of the most vulnerable continents, are due to a lack of financial, technical, and institutional capacity to cope with the impacts of climate change. Due to various anthropogenic activities, greenhouse gases are increasing in the atmosphere at an alarming rate, which leads to extreme temperatures, flooding, loss of soil fertility, low agricultural production (both crops and livestock), biodiversity loss, the risk of water stress, and the prevalence of various diseases. It is predicted that the temperature on the African continent will rise by 2 to 6°C over the next 100 years. In terms of economics, Sub-Saharan Africa will lose a total of US$26 million by 2060 due to climate change. The increasing occurrence of flooding and drought is also another predicted problem for Africa.

Impacts of climate change on agricultural yields in Africa

A strong agriculture sector is necessary for food security in Africa. According to a recent study, climate change is responsible for reducing agricultural yields by 21 percent worldwide over the last 60 years. 7 In this period, the cumulative impact of climate change has been greatest in relatively warm regions such as Africa, responsible for a 33 percent yield decline. Like this study, most others focus on the important impact of nonliving systems (e.g., sea level rise, increased temperatures, greater frequency and severity of storms and droughts) but not living systems, including agricultural pests and plant diseases.

Food insecurity in Africa: A baseline

Climate change is compounding food insecurity on a continent already severely afflicted by hunger and malnutrition. The Food and Agriculture Organisation of the UN’s (UN FAO) most basic estimate of food insecurity is the “prevalence of undernourishment,” describing the proportion of a population that lacks enough dietary energy for a healthy, active life. The prevalence of undernourishment is estimated to be 19.1 percent, or 250.3 million people, across Africa; populations in Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean are undernourished at less than half this rate (8.3 percent and 7.4 percent, respectively). 1 While the absolute number of undernourished people is lower in Africa (250.3 million) than in Asia (381.1 million) today, the UN estimates that Africa will be home to the highest prevalence and absolute number (25.7 percent, or 433.2 million) of undernourished people by 2030.

Ethiopia’s Green Legacy

Ethiopia, home to 120 million people, is one of the world’s most drought-prone countries. It has a high degree of vulnerability to hydro-meteorological hazards and natural disasters. Green Legacy, for a greener and cleaner Ethiopia, is a national go-green campaign endeavoring

to raise the public’s awareness about Ethiopia’s frightening environmental degradation and educate society on the importance of adapting green behavior. The Green legacy in Ethiopia encompasses more than just tree planting. The initiative entails broader environmental and sustainable development initiatives. The approach includes ecosystem restoration, biodiversity conservation, renewable energy promotion, and building a green economy.

Ethiopia’s Green Legacy also recognizes the importance of grassroots involvement, community participation, and ownership in environmental conservation efforts. It highlights the need for reforestation and restoration programs to be integrated into wider national development plans, ensuring long-term sustainability. The initiative in Ethiopia serves as an example of how environmental conservation and socioeconomic development can go hand in hand.

According to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Sustainable Development Ethiopia, Dependence on sectors that are climate change sensitive, such as rain-fed agriculture, water, tourism, and forestry, as well as a high level of poverty, are the main factors that exacerbate Ethiopia’s vulnerability. Ethiopia’s policy response to climate change has progressively evolved since the ratification of the UNFCCC in 1994.

Ethiopia launched the National Adaptation Plan of Action in 2007 and the Ethiopian Programme of Adaptation on Climate Change and Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions in 2010. Ethiopia also endorsed a Climate Resilient Green Economy (CRGE) strategy in 2011 with the objective of building a green and resilient economy. Over the years, Ethiopia has been implementing various programs within those policy frameworks. One among them, and by far the most consequential, has been the Green Legacy Initiative (GLI).

Rooted in a vision of building a green and climate-resilient Ethiopia, the Green Legacy Initiative was launched in June 2019.

The Green Legacy Initiative is a demonstration of Ethiopia’s long-term commitment to a multifaceted response to the impacts of climate change and environmental degradation that encompasses agroforestry, forest sector development, greening and renewal of urban areas, and integrated water and soil resource management. This has made an immense contribution to Ethiopia’s efforts to meet its international commitments, such as the Paris Climate Change Agreement, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want.

Green Legacy Initiative Expected Impact

Ethiopia’s Green Legacy Initiative has multiple targets, as it naturally touches on various targets of the 2030 Agenda. A contribution to food security is one of the objectives of the Initiative. In 2022 alone, more than 500 million seedlings were plants that have premium values in local and international markets, such as avocados, mangoes, apples, and papayas. This directly feeds into the current drive to become food self-sufficient by promoting sustainable agriculture, as envisaged in Sustainable Development Goal 2. The Initiative is a major flagship project that will help attain its adaptation goals as set in the National Adaptation Plan. Ethiopia is one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change.

Frequent droughts, floods, and locust infestations are some of the manifestations of extreme climate events. Over the past four decades, the average annual temperature in Ethiopia is estimated to have risen by 0.37 degrees Celsius each decade. Directly linked to Goal 13 of the SDGs, this Initiative complements Ethiopia’s efforts to reduce its vulnerability. Moreover, forest conservation, reforestation, restoration of degraded land and soil, as well as the promotion of sustainable management of forests Ethiopia’s forest coverage has been declining for decades at an alarming rate.

The Initiative intends to reverse this, as this is unsustainable in a country where 85 percent of the population depends on rainfed agriculture. Overall, the innovative aspect of the Initiative lies in its potential to address multiple objectives. This entails enormous benefits in environmental protection, restoration of overexploited and degraded natural resources such as surface soil and water, halting desertification, and many other interrelated objectives. The enormity of the interlinkages will significantly contribute to Ethiopia’s efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.

The Great Green Wall initiative

Similarly, The Great Green Wall initiative is a large-scale project aimed at combating desertification in the Sahel region of Africa, stretching from Senegal to Djibouti. While it is true that the project involves tree planting as a significant component, it encompasses much more than that. The Great Green Wall initiative recognizes that desertification and land degradation in the Sahel region are complex problems that require multifaceted solutions. It seeks to address several interconnected issues, including soil erosion, food security, water scarcity, climate change, and the livelihoods of local communities. The project uses a combination of techniques beyond tree planting, such as sustainable land management practices, agroforestry, and the promotion of alternative livelihoods for local people.

By focusing solely on tree planting, the media overlooks the holistic approach of the Great Green Wall initiative. While the afforestation component is crucial to restoring and increasing vegetation cover, it is just one part of a comprehensive strategy. The initiative aims to create a mosaic of restored landscapes, including forests, grasslands, and agricultural areas, to enhance ecological resilience and promote sustainable land use.

The Great Green Wall initiative is not solely aimed at halting the southward expansion of the Sahara Desert. It also aims to provide various ecosystem services, such as carbon sequestration, biodiversity conservation, and the provision of water resources. Additionally, the project seeks to support the socio-economic development of local communities by creating employment opportunities, boosting agricultural productivity, and fostering sustainable economies.

In conclusion, both the Great Green Wall initiative and Ethiopia’s Green Legacy are comprehensive responses to the environmental challenges faced by their respective regions. While tree planting is a prominent aspect, reducing these efforts to a single activity undermines the breadth and complexity of the initiatives. The media should strive to provide a more nuanced analysis by highlighting the multifaceted approaches, broader goals, and potential long-term impacts these initiatives can have on ecosystems, communities, and sustainable development.

Share

A Cost-Benefit Discussion on African Countries Joining BRICS

A Cost-Benefit Discussion on African Countries Joining BRICS

By Staff Writer

In recent years, economic self-empowerment and self-sufficiency by way of global cooperation mechanisms have shaped the foreign policy and economic strategy of many nations; particularly that of developing nations. As African countries strive for sustained development and inclusive growth, the possibility of joining the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) promises great potential. In light of the growing chatter about the prospects of BRICS that has saturated global affairs, it is of utmost importance to ask “What is the cost-benefit analysis for African countries in joining BRICS?” This piece discusses the broader implications of this organization, with a broad discussion on the plausible outlook of the United States. and the broader ‘West’ in this seeming move.

Embracing New Horizons: Benefits of Joining BRICS

Enhanced economic cooperation:BRICS offers African countries the potential for increased economic cooperation through fostering cross-border trade, investment, and technology transfer. This partnership can foster sustainable industrial development, promote job creation, and foster innovation, ultimately contributing to Africa’s long-term economic growth.

Infrastructure development prospects: BRICS nations possess tremendous expertise and resources in infrastructure development. By joining BRICS, African countries can tap into this bank of knowledge and experience, which is critical for addressing a significant infrastructure deficit. Access to funding from the New Development Bank presents an exciting opportunity to accelerate infrastructure projects continent-wide.

Diversifying partnerships & reducing dependence: Historically, African countries have relied heavily on Western powers for aid, investment, and trade. By joining BRICS, they can diversify their partnerships and reduce over-reliance on a particular geopolitical bloc. This diversification not only mitigates economic risks but also strengthens Africa’s bargaining power.

Weighing the Risks of BRICS

Perceived dependence on non-western powers: One potential cost is the perception that African countries may become over-reliant on non-Western powers by aligning with BRICS.

Critics argue that such dependence might compromise the African voice and hinder progress in areas such as human rights and democracy. However, it is essential to recognize the agency and autonomy of African nations in forging their own path toward development.

A shift in trade patterns: Joining BRICS could lead to a redirection of trade patterns towards these emerging markets. While this may disrupt long-established Western trade relationships, it also opens new opportunities for African nations to diversify their markets, expand trade volumes, and reduce their reliance on single trade partners.

The potential risk of isolation: Some detractors suggest that joining BRICS might isolate African countries from Western institutions like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. However, the formation of alternative financing mechanisms within BRICS, such as the New Development Bank, can address these concerns and provide African countries with access to much-needed capital for infrastructure and socio-economic development.

Pragmatic Concerns: Response of the US and the West

The United States and some Western powers have expressed concerns over African countries aligning with BRICS. This response can be seen as a manifestation of the historical geopolitical competition between the traditional Western powers and emerging economies. The US fears the dilution of its influence in Africa, given BRICS’ growing prominence. Consequently, they may adopt assertive measures to safeguard their interests, including reinforcing partnerships, revising aid policies, or promoting alternative economic alliances.

African countries joining BRICS offer immense potential for accelerated economic growth and sustainable development. The benefits of enhanced economic cooperation, infrastructure development, and diversified partnerships far outweigh the perceived costs. In the face of potential resistance from the US and Western powers, African nations must emphasize their sovereignty, maintain an assertive stance, and actively engage with the BRICS community to ensure shared prosperity. By strategically forging new alliances, Africa can unlock its true potential on the global stage.

Share

China's Expanding Military Presence in Africa: A Strategic Pursuit

China's Expanding Military Presence in Africa: A Strategic Pursuit

By Staff Writer

In recent years, China has made significant strides in establishing a robust and extensive military presence in Africa. Signaling its growing ambition for global prominence, China commenced this endeavor in 2017 with the construction of its naval base in Djibouti, East Africa’s strategic hub. As this military expansion unfolds, China seeks to build a second naval base in Nigeria, further solidifying its foothold on the African continent. For this reason, it is important to critically assess the motivations, implications, and potential ramifications of China’s increasing military presence in Africa to help shed light on the ever-evolving international political power dynamics.

China’s Naval Base in Djibouti:

China’s decision to establish a naval base in Djibouti highlights its drive to safeguard its ever-expanding economic interests and ensure uninterrupted lines of communication. Situated strategically at the southern entrance of the Red Sea, Djibouti offers China unparalleled access to the Gulf of Aden, the Arabian Sea, and the Indian Ocean. Furthermore, its proximity to volatile regions like the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula allows China to actively contribute to peacekeeping initiatives and counter-piracy efforts in the region.

The base in Djibouti symbolizes China’s transition from being a land-centric power to a formidable maritime force. By bolstering its naval presence in this strategically significant location, China aims to safeguard vital sea lanes upon which its burgeoning economy relies. Additionally, the base serves as a springboard for projecting soft power, boosting China’s diplomatic influence in the region, and enhancing its non-traditional security cooperation efforts, such as anti-terrorism and disaster relief operations.

Potential Second Naval Base in Nigeria:

With China’s military foothold in Djibouti firmly established, reports of a potential second naval base in Nigeria have gained considerable attention. Nigeria, being Africa’s largest economy and the most populous nation on the continent, presents immense opportunities for China. The establishment of a second naval base in Nigeria would not only enable China to extend its reach and influence along the resource-rich Gulf of Guinea but also bolster bilateral economic ties.

While the Nigerian government views this potential cooperation favorably, some observers express concerns about the long-term implications. Critics argue that an expanded Chinese military presence in Africa could fuel regional competition, exacerbate geopolitical tensions, and dilute Africa’s ability to assert its own interests. Furthermore, questions regarding the transparency of China’s intentions persist, leading to apprehensions about potential hidden military objectives behind ostensibly civilian-oriented projects.

Implications and Concerns:

China’s increasing military presence in Africa raises a host of broader implications with far-reaching consequences. As the United States, France, and other Western powers traditionally dominate African military engagements and continue to recalibrate their priorities, China’s entry has shifted the geopolitical dynamics in the region. This development has prompted existing powers to reassess their involvement, while African nations find themselves navigating a delicate balancing act in managing their relationships with multiple external actors.

Moreover, China’s military expansion raises questions about adherence to international human rights standards and non-interference principles. Some critics fear that China’s increasing military influence may undermine democratic governance, exacerbate conflicts, or inadvertently encourage autocratic regimes, impacting African states’ efforts toward good governance, human rights, and sustainable development.

China’s establishment of a naval base in Djibouti in 2017, followed by the potential construction of a second base in Nigeria, illustrates its ambitions to secure vital sea routes and ensure its expanding economic interests in Africa. While China portrays its military presence as a means to contribute to regional stability and enhance bilateral cooperation, concerns over potential hidden agendas and eroding regional autonomy persist. As African countries, both individually and as a block, navigate the shift in global geopolitical landscape, they must carefully evaluate the implications of China’s military presence on the continent while protecting their national interests, collective sovereignty, and safeguarding regional stability.

Share

Examining the Detriments of Russia-Africa Relations and Africa's Approach to the Upcoming Russia-Africa Summit in July 2023

Examining the Detriments of Russia-Africa Relations and Africa's Approach to the Upcoming Russia-Africa Summit in July 2023

By Staff Writer

As the Russia-Africa relations continue to evolve, it becomes crucial for African nations to objectively assess the benefits and drawbacks associated with this partnership. This article aims to shed light on the various reasons why Russia-Africa relations may not be as advantageous to Africa as perceived, and how Africa should approach the next Russia-Africa Summit scheduled for July 27-28, 2023.

The Limitations of Russia-Africa Relations:

1. Limited Diversification of African Economies: While Russia has shown interest in investing in African natural resources, there has been a dearth of diverse economic partnerships. Overreliance on the exploitation of Africa’s raw materials can undermine the continent’s long-term economic growth, hindering efforts to diversify its economies and promote sustainable development.

2. Unequal Trade Imbalance: Agreements and arrangements between Russia and African nations often result in an uneven trade balance, favoring Russian exports over African products. This imbalance reduces Africa’s economic gains and may perpetuate a cycle of economic dependency, limiting local industries from thriving and reaching their full potential.

3. Limited Technological Transfer: Although collaborations in sectors such as energy, defense, and infrastructure have taken place, the transfer of advanced technological know-how, research, and development remains limited. Without significant technology transfers, African nations may struggle to build independent technological capabilities and therefore restrict their ability to drive innovation and competitiveness in various sectors.

4. Political Influence and Geopolitical Considerations: The strategic interests of Russia may overshadow Africa’s individual national agendas in some instances. Such political influence can potentially hinder African nations’ autonomy in crafting policies that best meet their own developmental needs. African countries should strive for a balanced engagement that recognizes their own interests and avoids over-reliance on external powers.

There are several specific examples that can be cited to highlight the negative impact of Russia-Africa relations on African countries and their resources:

1. Exploitation of Natural Resources: Russia has engaged in resource extraction activities in African countries without adequate environmental regulations or sustainable practices. For instance, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Russian mining companies have been accused of poor labor conditions, illegal mining, and environmental degradation.

2. Arms Sales and Conflict: Russia has been a major supplier of arms to African countries, including those involved in regional conflicts. These weapons often exacerbate existing conflicts and fuel violence, causing immense human suffering and hindering development efforts.

3. Debt Dependency: Russia has provided loans to several African countries, which has resulted in substantial debt burdens. For instance, Angola owes Russia billions of dollars in debt from arms purchases. These debts create economic dependencies, diverting resources away from developmental projects and social welfare programs.

4. Lack of Technology Transfer: Russia often lacks technology transfer agreements or investments in African countries, which limits the building of local capacities and skills. Instead, Russia tends to export finished products, leading to less value-added economic activities in Africa.

5. Centralized Power Structures: Russian investments and partnerships often strengthen authoritarian regimes in Africa, thereby exacerbating corruption, lack of transparency, and further entrenching power imbalances. This can have detrimental effects on governance, democracy, and human rights.

6. Limited Infrastructure Development: While Russia has invested in certain infrastructure projects in Africa, the focus has mainly been on extractive sectors rather than broader developmental infrastructure. This limited focus hinders sustainable development and diversification of African economies.

7. Lack of Technology and Knowledge Transfer: Russian involvement in African countries has not always prioritized knowledge transfer or technology sharing. This results in missed opportunities for African countries to develop local capabilities and benefit from technological advancements.

It is important to note that while these examples highlight negative impacts, Russia-Africa relations also present opportunities for both parties. However, it is crucial to ensure that such relationships are mutually beneficial, sustainable, and support the long-term development goals of African countries, rather than merely exploiting their resources.

Approaching the Next Russia-Africa Summit (July 27-28, 2023):

1. Strengthened Preparatory Research: African nations must conduct comprehensive research and analysis to identify strategically crucial areas for collaboration that will yield mutual benefits. This approach will allow for more informed decision-making, ensuring that African interests are prioritized during negotiations.

2. Promoting Trade Diversity: African countries should seek to negotiate fair trade agreements that enhance diversification of their exports and reduce dependence on a single partner. Encouraging Russian investments in value-addition industries across Africa can contribute to economic transformation and greater self-sufficiency.

3. Emphasizing Technological Transfers: The upcoming summit provides an opportunity for African nations to foster partnerships that prioritize technological transfers and capacity-building initiatives. This will enable Africa to acquire advanced expertise, empowering local industries and facilitating technology-driven advancements across different sectors.

4. Strengthening Regional Integration: Africa’s unity is crucial in engaging with external partners like Russia. Collaborating as regional blocs will increase negotiating power and enable African countries to secure more favorable economic, social, and political partnerships.

Conclusion:

While Russia-Africa relations have the potential to bring about mutually beneficial collaborations, it is imperative for African nations to approach this partnership with careful consideration. By focusing on diversifying economies, promoting fair trade, prioritizing technology transfers, and strengthening regional integration, Africa can leverage the upcoming Russia-Africa Summit in 2023 to navigate these relations in a manner that will effectively drive sustainable development for the continent.

Share

Illegal mining practice in Ethiopia

Abstract

Illegal mining has become a significant problem in Ethiopia, particularly in recent years, with Chinese involvement in the sector being one of the aggravating factors. Such actors were recently discovered to have been hiding behind various investment schemes in Ethiopia. By analyzing information from reliable sources, academic papers, government reports, and other news articles, we aim to examine the extent of illegal mining in Ethiopia given its implications on the environment, economy, and society at large.

Mining is one of the key industries in Ethiopia, contributing to the country’s economic growth and development. According to the Economic Commission for Africa, the sector accounts for 14% of the country’s exports and is projected to account for 10% of the nation’s GDP. Given that the sector is relatively underexplored and untapped, it has attracted foreign investment interests, particularly from China. However, illegal mining has become a significant challenge in the country’s economy- not only due to the loss in national revenue but also due to its adverse effects on environmental, ecological, and societal well-being. Illegal mining involves extracting precious minerals without the required licenses and permits, and it often comes with unsafe mining practices and severe environmental degradation.

The Extent of Illegal Mining in Ethiopia

Illegal mining has become a significant challenge in Ethiopia, especially in the regions with significant mineral deposits, such as the Oromia, Benishangul- Gumuz, Tigray, Somali, and Southern regions. A report by the Ethiopian Geological Survey (EGS) states that illegal gold mining has been widespread in Ethiopia, with an estimated 60,000 to 70,000 artisanal miners operating in the country. These artisanal miners operate without licenses and often use crude methods that harm the environment, such as using cyanide to extract gold from ore.

The impact of illegal mining is visible in various ways. For instance, illegal/ unregulated mining activities cause deforestation, soil erosion, water pollution, and the destruction of agricultural land. This has a significant impact on the environment, affecting agriculture, biodiversity, and climate variability. Illegal mining also creates social problems, such as the displacement of people, human rights abuses, and inhumane and unsafe working conditions that often lead to injuries and fatalities.

Chinese Involvement in Illegal Mining in Ethiopia

The involvement of Chinese companies in illegal mining in Ethiopia has been reported by various sources.

Although Chinese companies, that often present themselves as investors, have denied these allegations; their actions suggest otherwise. In some cases, Chinese workers were found engaging in illegal mining, exploiting the country’s mineral resources without the necessary licenses and permits.

In other cases, Chinese companies have been accused of using Ethiopian employees as “fronts” for their illegal gold mining operations to avoid legal scrutiny.

Moreover, Chinese investment in Ethiopia’s mining industry may also be further exacerbating the problem of illegal mining. In Ethiopia, Chinese companies have invested heavily in the mining sector, with an investment of US$1.6 billion in 2018 alone. However, this investment has not necessarily helped Ethiopia’s mining sector to comply with environmental and social regulations. Instead, Chinese companies have been accused of using their investment as a cover to engage in illegal mining activities, and extraction of minerals without legal backing and adequate environmental protection measures. Chinese companies operating in Ethiopia’s mining sector have been accused of ignoring environmental regulations and collaborating with Ethiopian employees to engage in illegal mining activities.

The government of Ethiopia recently announced that 28 Chinese nationals in the country, with different visas, were caught red-handed in illegal mining activities. They were discovered to have been working hand-and-glove with local partners, who were since apprehended, in their illicit mining activities.

The problem of illegal mining in Ethiopia has far-reaching implications for the environment, economy, and society of the country. It is crucial that the Ethiopian government and the international community take effective measures to curb illegal mining activities, protect the environment, and ensure that investments in the mining sector adhere to sustainable practices and human rights principles. Given Ethiopia’s ambitious goal of growing the mining sector to account for 10% of the country’s GDP: as outlined in the National Growth and Transformation Plan, sustainable investment and responsible mining practices should be the ultimate goal for Ethiopia’s promising mining industry

References:

Chinese investment in Ethiopian mining growing | World Finance. (2018). World Finance. https://www.worldfinance.com/inward-investment/chinese-investment-in-ethiopian-mining-growing

Ethiopia re-evaluating Chinese mining contract. (2018). The East African. https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/business/Ethiopia-re-evaluating-Chinese-mining-contract/2560-4294776-9js2drz/index.html

The environmental impact of illegal mining in Ethiopia | The Ethiopian Herald. (2020). The Ethiopian Herald. https://www.ethpress.gov.et/herald/index.php/news/national-news/item/18978-the-environmental-impact-of-illegal-mining-in-ethiopia

Yu, H. (2019). Impact of small‐scale gold mining on water quality: The case of gambella region, Ethiopia. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A, 54(12), 1246–1252. https://doi.org/10.1080/10934529.2019.1672907

Share

What is in Belt & Road Initiative for African Continental Free Trade Agreement?

What is in Belt & Road Initiative for African Continental Free Trade Agreement?

By Endalkachew Sime (Ph.D. Candidate, Peking University)

Mr. Endalkachew Sime has extensive experience in the Ethiopian private sector working in progressive leadership positions in key sectors of the economy for more than a few couple of decades. Having obtained his first degree in Agricultural Economics and his second degree in Development Economics, Mr. SIME also worked as a Senior Economic Advisor, and board member representative for the African Cotton and Textile Industries Federation (ACTIF) and COMESA Business Council (CBC). He has worked as the Secretary General of the national private sector organization, the Ethiopian Chamber of Commerce and Sectoral Association (ECCSA), as well as the CEO of the Ethiopian Textile and Garment Manufacturers Association (ETGAMA). Most recently, Endalkachew Sime served a term as a State Minister of the Ministry of Planning and Development of Ethiopia. Mr. Endalkachw is currently a Ph.D. student at Peking University, Institute of South-South Cooperation and Development (ISSCAD), majoring in National Development.

I. Introduction

This article tries to explain the relevance of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) for the four-year-old African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA). In doing so, the article attempts to site counter-intuitive examples to gauge the claim of Shaffer and Gao (2020), which considers BRI as a re-purposed exporting tool of the Chinese development model aims at nurturing the new Sino-centric economic order that stretches to ‘outgrow’ the existing Western-led liberal model of development. In the following sections, we will see the critical gap BRI could fill in the new continental economic development space being created under AfCFTA against the above backdrop. This article concludes by proposing actionable recommendations based on observed limitations, targeted to key stakeholders of BRI mainly China, as well as decision-makers of the African Union and its member states as an audience.

II. The African Continental Trade Agreement (AfCFTA)

Having more than 16% of the global population, Africa’s share of global trade and GDP remains as small as 2.1% and 2.9% respectively (IMF, 2020). And Africa has embarked upon a development plan called ‘Agenda 2063’ to change this situation.

According to the African Union Commission (2015), Agenda 2063 is a 50-year development blueprint prepared by the African Union (AU) in 2013 and forwards a vision of building an integrated, prosperous, and peaceful Africa by 2063. Creating One African Market through the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) is one of the flagship projects of Agenda 2063.

AfCFTA is an agreement that provides a framework for trade liberalization of goods and services among African countries. Once fully implemented, AfCFTA is expected to cover all 55 African countries with an estimated combined GDP of US$2.5 trillion and a population of over 1.2 billion. In terms of population, the AfCFTA will be the largest free trade area in the world (IMF, 2020).

After its launch in May 2019, 54 of the 55 African counties endorsed AfCFTA and moved to implementation on January 1, 2021. Its implementation entails the gradual dismantling of tariffs on 97 percent of intra-African trade over 13 years. Full implementation of the agreement is forecasted to boost intra-African trade from 13% to around 52% (A. Mold, 2022).

According to World Bank (2020), the full implementation of the AfCFTA has the ability to lift 30 million Africans out of extreme poverty and boost the incomes of nearly 68 million others who live on less than $5.50 a day by boosting wages for skilled workers by 9.8% and the wages for unskilled workers by 10.3%.

But Africa’s large infrastructure deficit in roads and ports are among the major challenges hindering AfCFTA implementation. Estimates by the African Development Bank (AfDB, 2018) show that the continent’s infrastructure needs amount to $130–170 billion a year, with a financing gap in the range of $68–108 billion. The same document shows Poor infrastructure shaves on average up to 2 percent off Africa’s average per capita growth rates.

On the other hand, debt distress is affecting African nations’ eligibility for international infrastructure financing. According to China Daily (2022), from 1970 to 1987, the ratio of total external debt to GDP in African countries skyrocketed from an estimated 16% to 70%. And unsettled multilateral debt obligations rose from $58.7 billion to $110.45 billion between 2010 and 2018. This critically challenges the loan-soliciting efforts of African nations to finance their infrastructure gaps.

In summary, there is a pressing need to address Africa’s infrastructure gap to make the attractive promises of AfCFTA a reality. But on the other hand, debt stress is shadowing the attractiveness of Africa for International financers.

III. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)

The Belt and Road Initiative – China’s proposal to build a Silk Road Economic Belt and a 21st Century Maritime Silk Road in cooperation with related countries – was unveiled by Chinese President Xi Jinping during his visits to Central and Southeast Asia in September and October 2013 (Silk Road Briefing, 2021).

Infrastructure connectivity is high on the BRI agenda. According to Silk Road Briefing (2021), as of April 2020, China had invested in BRI projects in 42 different African countries in 74 Ports either as developers or operators, or both. One of the most noticeable discussions around these projects includes the study by Shaffer and Gao (2020). This paper considers BRI as non-original thought but a repurposing of an existing one. It further depicts BRI as an exporting tool of the Chinese development model with the purpose of building a new Sino-centric economic order that emphasizes the key role played by the government through massive infrastructure investments. Such a move, according to the paper, contrasts the liberal model of development of the West, grounded in private enterprise and market competition. This short article lacks the necessary scope and depth to prove or disprove the diverse list of claims described in the paper.

But rather, it tries to shed light on what is BRI for Africa especially in the context of the crying need of Africa to harness its new opportunity seen in AfCFTA. Let us cite a specific example, the Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway (AADR) project, whether Shaffer and Gao’s claim of China’s imposition of development model has got space on the ground or not.

After 1992, when a couple of Ethiopia’s Red Sea ports (Asab and Massawa) were lost to the then-new state of Eritrea and Ethiopia became land-locked, the port-related logistics were a growing concern for the Ethiopian economy. Many research discussions were being made both in the government as well as in the private sector, especially in the Ethiopian Chamber of Commerce. And through the proactive move of the Ethiopian government and cooperative responses from the Chinese government, the Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway (AADR) became a reality in 2017.

According to Capital Ethiopia (2022), before AADR replaces the century-old Italian-built Ethio-Djibouti railway in 2017, containers were taking more than 3 days to reach Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, from Djibouti port. The electric-driven AADR has reduced the 3 days to less than 20 hours and has also reduced the cost by at least one-third. The same report shows that the volume of goods transported is increasing by 25% every year on average, which was interrupted during the COVID-19 period.

Therefore empirically speaking, the above reality shown with AADR project, as part of BRI, does not go with the conclusion made by Sheffer and Gao, which describes BRI as a Sino-centric tool of exporting China’s development model to build a new global economic order.

IV. Challenges – sustainability and performance

Key stakeholders, especially the African Union and member states need to give attention to sustaining the growing role of BRI in addressing Africa’s infrastructure gap. According to R. Bociaga (2023), Belt and Road investment in sub-Saharan Africa fell by 54% in 2022, to $7.5bn from $16.5bn in 2021, according to a recent report from the Green Finance and Development Centre at Fudan University in Shanghai. The reason behind such changes needs to be closely followed up. The above report also explains, since December 2019, the US Congress has been funding a ‘Countering Chinese Influence Fund’ used by the executive branch to challenge Chinese influence, including through the BRI, in Africa and elsewhere. African Union and member states need to be aware of such situations that might reduce the growing Africa-BRI cooperation and take the necessary actions.

The other challenge is related to implementation and project management. All BRI projects in Africa are not successful. There should be a detailed performance evaluation of projects that leads to the success of all projects, which is important to attract more investments.

V. A Way forward?

For a better realization of AfCFTA’s aspirations, BRI can be taken as one strategic opportunity to address the infrastructure gaps in Africa. But what are the key points key stakeholders should give attention to?

1. Strategic planning on Infrastructure

Efficient utilization of expensively built infrastructure helps in addressing the growing concern of debt distress in Africa. The best way to address this is to strategically align each infrastructure project into the country’s national development plans.

2. Cross border Infrastructure for Intra-Africa Connectivity

It is common to plan and build infrastructures at a country level. But cross-border initiatives like AfCFTA needs cross-border infrastructure planning that connects compatible comparative advantages of neighboring countries.

Learning from others on the intra-regional trade-building process.

Even though Africa has been dealing with many RECs (Regional Economic Cooperation) and trade agreements, AfCFTA is a huge task for the AU and member states to deal with 54 fragmented market spaces with diverse statuses and political-economic thinking. Africa can learn a lot from Asia in this aspect. Osvaldo R. (2007) explains that mounting evidence suggests trade liberalization and the ability of much of Asia to respond flexibly to world demand is the best explanation for the spectacular growth of South-South trade.

Therefore, the South-South Cooperation (SSC) platform should be seen by AU and member states as one soft capacity-building opportunity. SSC has gained good momentum in its relatively intensive past engagements in Asia, which can be used by Africa to learn from past experience.

Improving debt management capacity

The other learning area for Africa is debt management. The spectacular promises of AfCFTA we have seen above in figures are trapped in challenges such as infrastructure gaps. On the other hand, debt distress is a growing challenge in the continent. And as recommended by A. Mugasha (2007), Trade and proper debt management are the two solutions for the growing debt of middle-income developing countries. Prudent and strict implementation of the plans of AfCFTA enables Africa to gain from its intra and inter-Africa Trade for its debt distress. But on the other hand, the debt management capacity of Africa needs special emphasis. The available menu of options for debt management, as explained by A. Mugasha (2007) includes securitization, secondary markets, renegotiation including debt write-off as well as debt-for-equity schemes. The capacity of Africa to implement such debt management schemes should be strengthened both at the continental organization level such as AU and AfDB, as well as at the level of the member states.

African Development Bank.(2018).African Infrastructure, African Economic Outlook. Retrieved April 27, 2023, African_Economic_Outlook_2018_-_EN_Chapter3.pdf (afdb.org)

Agasha M. (2007). Solutions for Developing-Country External Debt: Insolvency or Forgiveness, Law and Business Review of the Americas, Vol. 13, No. 4, pp. 859-883.

Andrew, M.(2022).The Economic Significance of Intra-African Trade: Getting the narrative right, Brookings Global Working Paper #44, Africa Growth Initiative at Brookings.

Capital Ethiopia Newspaper. (2022), Ethio-Djibouti Railway. Retrieved April 30, 2023. ETHIO-DJIBOUTI RAILWAY – Capital Newspaper (capitalethiopia.com)

Cernat, L. and Laird, S. (2003). North, south, east, west: what’s best? Modern RTAs and their implications for the stability of trade policy, Paper No. 03/11, Centre for Research in Economic Development and International Trade (CREDIT), University of Nottingham, Nottingham, available at: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id ¼ 456941

Chris, D.(2021). China’s African Belt & Road Initiative – It’s Not What You Think It Is, Silk Road Briefing. China’s African Belt & Road Initiative – It’s Not What You Think It Is – Silk Road Briefing

G. Shaffer and H. Gao.(2020). A New Chinese Economic Order? Journal of International Economic Law, 2020, 23, 607–635, Oxford University Press..

Lisandro, A., Brego, M., Tunc, G., Salifou, I., Garth, P., Nicholls, H. and Jose-Nicolas, R.(2020). The African Continental Free Trade Area: Potential Economic Impact and Challenges; IMF.

Osvaldo R. (2007). Is South-South trade the answer to alleviating poverty? Management Decision, pp. 1252-1269.

Robert T. (2019). The Belt and Road Initiative and Africa’s regional infrastructure development: Implications and Lessons, Transnational Corporations Review, Volume 12, 2020 – Issue 4: Pages 425-438.

The African Union Commission. (2015). Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want – A Shared Strategic Framework for Inclusive Growth and Sustainable Development First Ten Year Development Plan, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

World Bank. (2020). The African Continental Free Trade Area: Economic and Distributional Effects. Washington, DC The African Continental Free Trade Area (worldbank.org)

World Trade Organization (2004). Selected features of South-South trade developments in the 1990-2001 period, World Trade Report, World Trade Organization, Geneva. Retrieved May 1, 2023. www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/anrep_e/

world_trade_report_2003_e.pdf

Robert B. (2023) US and EU investment in Africa challenges China’s Belt and Road, the Africa Report, Kampala, Uganda. Retrieved May 2, 2023. US and EU investment in Africa challenges China’s Belt and Road (theafricareport.com)

Xin P.(2022). Africa’s debt crisis: Who are the culprits?, China Daily. retrieved April 27, 2023, Africa’s debt crisis: Who are the culprits? – Chinadaily.com.cn.

Share

The State of Counter-Terrorism Coordination in Africa and the Fated Decline of Al-Shabaab Staff Writer

The State of Counter-Terrorism Coordination in Africa and the Fated Decline of Al-Shabaab

By Staff Writer

Terrorist groups have continued to wreak havoc in many parts of the world, causing fear, destruction, and loss of lives. Africa has not been immune to this problem, with various extremist groups wreaking havoc in different regions of the continent. One such group is Al-Shabaab which started as a small faction in Somalia and eventually grew to become one of the most formidable terrorist organizations with a vast network in Africa. However, with the concerted efforts of African states and international partners, there has been a remarkable decline in Al-Shabaab’s power and influence. This article explores the state of counter-terrorism in Africa and the factors that led to Al-Shabaab’s downfall.

The Rise of Al-Shabaab

Al-Shabaab is an Islamic extremist group formed in Somalia in 2006. Its main aim is to establish an Islamic State in Somalia and impose Sharia law on the people. Although the group started as a relatively small faction, it gained momentum and popularity due to its ability to provide basic services such as healthcare, education, and security in areas where the Somali government had failed. This made it easier for the group to recruit members, particularly among the youth that feels disenfranchised and marginalized by the government.

This made it easier for the group to recruit members, particularly among the youth that feels disenfranchised and marginalized by the government.

Al-Shabaab’s activities expanded beyond Somalia, with the group launching attacks in neighboring countries such as Kenya, Uganda, and Ethiopia. These attacks often targeted civilians, government officials, and military personnel, intending to undercut government apparatus, spread fear, and further destabilize the region. Al-Shabaab funds its activities through various illicit means, such as extortion, piracy, and smuggling. It also receives financial and logistical support from international terrorist organizations such as Al-Qaeda.

The State of Counter-Terrorism in Africa

African states and their international partners have made significant strides in countering terrorism in the continent in recent years.

African states and their international partners have made significant strides in countering terrorism in the continent in recent years. One of the key strategies adopted by African governments is the formation of regional and sub-regional organizations to coordinate counter-terrorism efforts. For instance, the African Union (AU) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) have established regional counter-terrorism centers that provide training, intelligence sharing, and joint operations among member states.

International partners, particularly the United States, have also provided support to African states in the fight against terrorism.

This support includes training, equipment, intelligence sharing, and financial assistance. In addition, the U.S. has established a military presence in Africa through the United States Africa Command (AFRICOM), which coordinates military operations and provides logistical support to African states.

The Downfall of Al-Shabaab

Despite its initial success, Al-Shabaab has suffered a significant decline in recent years due to concerted efforts by African states and international partners. One of the key factors that led to the group’s downfall was the increased military pressure on its strongholds in Somalia. With the support of the AU and U.S. forces, the Somali government launched several offensives against Al-Shabaab, leading to the group losing control of many towns and villages. The group also suffered significant losses regarding the number of fighters and leaders killed or captured.

Another factor that contributed to Al-Shabaab’s decline is the disruption of its financial networks. African states and their international partners have taken measures to track and disrupt the group’s illicit financing activities, cutting off its ability to fund its operations. In addition, the group has struggled to maintain popular support due to its brutal tactics, including the use of child soldiers, the recruitment of young people through deception, and the imposition of harsh punishments on civilians.

Going forward, African states and their partners must continue to work together to address the root causes of terrorism, including poverty, marginalization, and political instability, if they are to ensure sustained peace and security in the region.

The rise of Al-Shabaab in Somalia posed a significant challenge to the stability and security of the region. However, with the concerted efforts of African states and international partners, the group has suffered a significant decline in recent years. The strategies adopted, including military pressure, financial disruption, and the provision of basic services to areas previously underserved, have been critical in countering the group’s activities. Going forward, African states and their partners must continue to work together to address the root causes of terrorism, including poverty, marginalization, and political instability, if they are to ensure sustained peace and security in the region.

Reference:

Pham, J. P. (2018). State of the Terrorist Threat in Africa. Linchpin Strategies, LLC.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2020). Terrorism Prevention – Africa. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/terrorism/prevention-africa.html

United States Department of Defense (2018). “Special Briefing on U.S. Counterterrorism Efforts in Africa”. https://www.defense.gov/Newsroom/Transcripts/Transcript/

Article/1608536/special-briefing-on-us-counterterrorism-

efforts-in-africa/

Share

Is the United States a better-suited ally than China? An Exploration of United States' Comparative Advantage in Africa

Is the United States a better-suited ally than China? An Exploration of United States' Comparative Advantage in Africa

By Yirga Abebe

Yirga Abebe is currently a Ph.D. student at the Institute for Peace and Security Studies of Addis Ababa University. He holds a Bachelor of Arts Degree in Political Science and International Relations from Dire Dawa University in 2010 G.C and a Master of Arts Degree in Peace and Security Studies from the Institute for Peace and Security Studies of Addis Ababa University in 2014 G.C. Yirga has more than 10 years of professional experience in education and research in Ethiopian institutions of higher learning. He was a lecturer at Wollo University, Department of Peace and Development Studies, from September 2018-January 2021, and Jigjiga University, Department of Political Science and International Relations, from September 2010-August 2018. In addition to teaching, Yirga is actively engaged in conducting research on various themes at local, national, and regional level initiatives including customary conflict resolution, pastoral conflict management, conflict-induced displacement, women & election, parliament, and conflict management, peacebuilding, conflict trends, and geopolitical dynamics.

Africa has long been a center of intense rivalry between major powers. The continent has one of the world’s fastest-growing populations, the world’s most diverse ecosystems, abundant natural resources, and one of the largest voting blocks in the United Nations Assembly. The United States and China have been vying for political, economic, and regional influence in Africa since the early 2010s; it has, in recent years, intensified and brought ideological and geostrategic divisions to full display. The history and current state of relations that the two countries have with Africa are vastly different, both in the nature and magnitude of their engagements.

The US and Africa have a long and tumultuous history; since the second half of the 20th century, the relations between the US and Africa have gone through at least three major phases each with different features: during the Cold War, during the transitional period between 1990 to 1998, and after 1998. On August 2022, the United States adopted a new strategy towards Sub-Saharan Africa. Articulating a new vision for a 21st Century U.S.-African Partnership, the strategy aims to pursue four main objectives in sub-Saharan Africa:

foster openness and open societies; deliver democratic and security dividends; advance pandemic recovery and economic opportunity; and support conservation, climate adaptation, and a just energy transition.

China’s activities in Africa date back to the continent’s pre-independence period, when ideologically driven Beijing supported liberation movements fighting colonial powers. Nowadays, China is Africa’s largest trading partner, hitting $254 billion in 2021, exceeding by a factor of four US-Africa trade. China has become a preferred investment partner, a source of accessible loans for African countries across the board. Chinese funds back a wide range of projects from transportation to energy and minerals, medicine, agriculture, and telecommunications. However, these engagements are not without certain drawbacks.

For Africa, both the US and China have come up with their own comparative advantages/benefits. These factors would also benefit African countries and are the main reasons why African countries should favor closer ties with the United States than with China. What follows is a brief discussion of the US’s comparative advantages to the African continent at large.

Demographic factors

There is a large number of African descent living in the USA. This has a long history tracing back to the trans-Atlantic slave trade between the 16th and 19th centuries. It is indicated that 12% of the USA population, around 43 million, are of African descent.

It is estimated that over 28.3 million sub-Saharan Africans reside outside their countries of origin. Of these, while about 17.8 million (63%) lived elsewhere within the region, the United States is the top destination for sub-Saharan Africans outside the region. There are approximately 2.1 million sub-Saharan African immigrants who resided in the United States in 2019. 53 % of these immigrants came from Nigeria, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, or Somalia. On the other hand, there are 381,000 immigrants in the United States from North African countries mainly Egypt, Morocco, and Sudan. In comparison, the number of Africans in the USA is by far greater than an estimated 500,000 African migrants that live in China, many of which are merchants. This led the USA to have an advantage over China in its engagement in Africa.

African’s positive perception of the US is slightly greater than China

According to a survey conducted by Afrobarometer in 2019 and 2020 in 18 African countries, China and the United States are placed in roughly equivalent positions as external influencers. Asked about their perceptions of the economic and political influence of the two powers, 59% of African respondents viewed China somewhat, or very, positively and 15 percent viewed China somewhat or very negatively. The comparable numbers for the United States were similar: 58% in positive and 13% in negative view. The same study reported that, when respondents were asked to name the best national model for development, 32% cited the United States, and 23% named China. Moreover, many scholars anticipate that Africans’ positive perceptions of the United States may continue to increase during the presidency of Joe Biden. This positive perception that Africans have towards the United States, somehow greater than China, will be an advantage to be utilized while engaging in Africa.

The spread of democracy, human rights, and civil societies

The US is best known for safeguarding liberal principles and institutions. The promotion of democracy, human rights, and civil societies has been an integral part of the US’s domestic and foreign policies. This in turn contributes to the spread of these values and institutions across Africa. This has enabled to empower the people so that they can exercise their power to elect and scrutinize their governments. It makes it somewhat more difficult for African governments to get away with blatant and excessive abuses of power in due course of governing. As many of the public services in Africa are not only provided by the government, the emergence of local/national/international civil societies in African countries, which is the by-product of the US’s engagement, will fill this vacuum.

On the other hand, Chinese engagement in Africa is often criticized for lack of transparency as many business practices are claimed to be fraudulent, abusive, and corrupt. Similarly, China is also accused of undermining the strengthening of democratic institutions and governance in Africa as it continues to invest in countries with governance challenges such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Conflict resolution and security diplomacy

The US usually assumes a larger diplomatic role in the overall efforts to resolve African conflicts. Despite its ever growing influence and increasing commercial engagement, China’s diplomacy has traditionally kept a non-partisan stance concerning inter and intra-state conflicts, and their resolution attempts, in Africa.

It is stated that although Beijing did appoint a special envoy for the Horn of Africa earlier in 2022, it has not been active in diplomacy surrounding the war in Northern Ethiopia as might be expected given its heavy investment in the country. While the African Union has taken the diplomatic lead, the United States was playing both a public and behind-the-scenes role in Ethiopia.

China has traditionally adopted a “non-interference” policy in African and global conflicts. However, this policy seems to have evolved with its new Belt Road Initiative (BRI) over the past 10 years. In February 2023, Beijing launched its Global Security Initiative, with the aim of “peacefully resolving differences and disputes between countries through dialogue and consultation”.

The US has a strong military and security presence in Africa. According to the US African Command, there are a total of 29 US military bases located in 15 different countries in Africa in 2019. These bases are categorized as an “enduring footprint” (a permanent base) and those with a “non-enduring footprint” or” (semi-permanent or contingency base). On the other hand, China established its first overseas military base in Djibouti in 2017. In general, the US has more leverage in terms of conflict resolution and security diplomacy than China which is known for its emphasis on economic diplomacy. This will enable to maintain military and security ties between Africa and the US.

Strong humanitarian engagement

The US has been more strongly engaged in humanitarian sectors, than Chinese, in sub-Saharan Africa. The U.S. gave out $97.67 billion between 2000 and 2018 in Official Development Assistance to sub-Saharan Africa, with infrastructure projects (48 percent of total aid) and humanitarian aid (26 percent) being the top priorities. The health sector was given $6 billion, the agriculture sector received $4.2 billion, and $3.5 billion was committed to education. In Fiscal Year 2021, USAID and the U.S. Department of State provided $8.5 billion of assistance to 47 countries and 8 regional programs in sub-Saharan Africa. China’s global foreign aid expenditure has reached $3.18 billion in 2021. Between 2013 and 2018, 45% of China’s around $26 billion foreign aid went to Africa, much of this aid went to transportation, energy, and communication sectors. Unlike the Chinese development priorities in Africa, United States development efforts place greater emphasis on health, education, and other humanitarian sectors.

Diaspora Remittances

There is a large number of African diaspora in the USA. According to Migration Policy Institute (2022), the number of sub-Saharan African diaspora in the United States is more than 4.5 million. The figure is expected to increase considering the number of Diasporas in the USA from North African states. The African diaspora living in the US, Europe, and elsewhere send back significant amounts in remittances to the continent. World Bank figures show that there is a total of $95.6 billion in remittance flows to Africa in 2021, of which $46.6 billion went to North Africa and $49 billion to sub-Saharan Africa. The extent of remittance is more favorable than the official development assistance to Africa of $35bn and foreign direct investment to sub-Saharan Africa of $88bn in 2021.

Chinese debt trap policy

Acknowledging this role, the African Diaspora has been among the priority issues in the US-Africa Leaders’ Summit which was undertaken in Washington DC on December 2022. It is also pronounced that the Biden administration will provide targeted support to small- and medium-sized businesses “with a specific focus on the African diaspora and their businesses and investors across the United States”. Therefore, the African diaspora, their business, and remittances will serve as an entry point for US’s comparative advantage over China related to Africa.

China is undoubtedly Africa’s largest bilateral creditor and a crucial partner in pioneering infrastructure development projects. Chinese loans have resulted in a significant debt held by African states. It is stated that overall external debt held by governments in the continent has doubled in two years, from a 5.8 percent average of government revenue in 2015 to 11.8 percent in 2017. Some African nations do have extensive Chinese loans and are suffering from out-of-control debt, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, high-interest rates, and other factors. While maintaining its image as a friend of developing nations, the extensive Chinese loans made to African countries will create the possibility of forced repayments, another headache to the continent’s development.

Some Pitfalls of Chinese Engagement in Africa

China is often criticized for an unfair and lack of a long-term strategy when engaging Africa. Compared with the US, the quality and standard of Chinese businesses in Africa is questionable. Its strategy is more about exploiting African natural resources than spurring the continent’s development, which also raises questions about sustainability for future generations in the continent and environmental concerns as well. In this regard, former President of the USA, Barack Obama, once said:

We don’t look to Africa simply for its natural resources. We recognize Africa for its greatest resource which is its people and its talents and its potential. We don’t simply want to extract minerals from the ground for our growth. We want to build partnerships that create jobs and opportunities for all our peoples that unleash the next era of African growth […]

While it is common to assume that China has been deeply engaged in Africa even surpassing the US, there is a repertoire of comparative advantages that the US offers to Africa. These stem from the US’ own strengths, as well as the pitfalls of Chinese engagement in the continent. These include factors related to demography, African perception, democracy, diaspora remittances, and strong engagement of the US in conflict resolution, security, and humanitarian-led diplomacy, on the other hand, China’s debt trap strategies and its trade practices in Africa present the United States as a better-suited ally.

Foreign Aid to Africa: The United States vs. China | The Borgen Project. April 2018.

Sino-African Migration: Challenging Narratives of African Mobility and Chinese Motives| China Focus. August 2021.

“A Brief History of U.S.-Africa Relations” in “United States-Africa Relations in the Age of Obama” | Cornell University Press Digital Platform.

Pentagon Map Shows Network of 29 U.S. Bases in Africa | The Intercept. February 2020.

The Eagle and the Dragon in Africa: Comparing Data on Chinese and American Influence | War on the Rocks.| May 2021.

The US and China in Africa: Competition or Cooperation? | Brookings. April 2014.

10 Things to Know about the U.S.-China Rivalry in Africa | United States Institute of Peace. December 2022.

US Strategy Toward Sub-Saharan Africa | The White House. August 2022.

Share

A Humanitarian Lifeline for Sudan’s Population: A Possible Ethiopian Role

A Humanitarian Lifeline for Sudan’s Population: A Possible Ethiopian Role

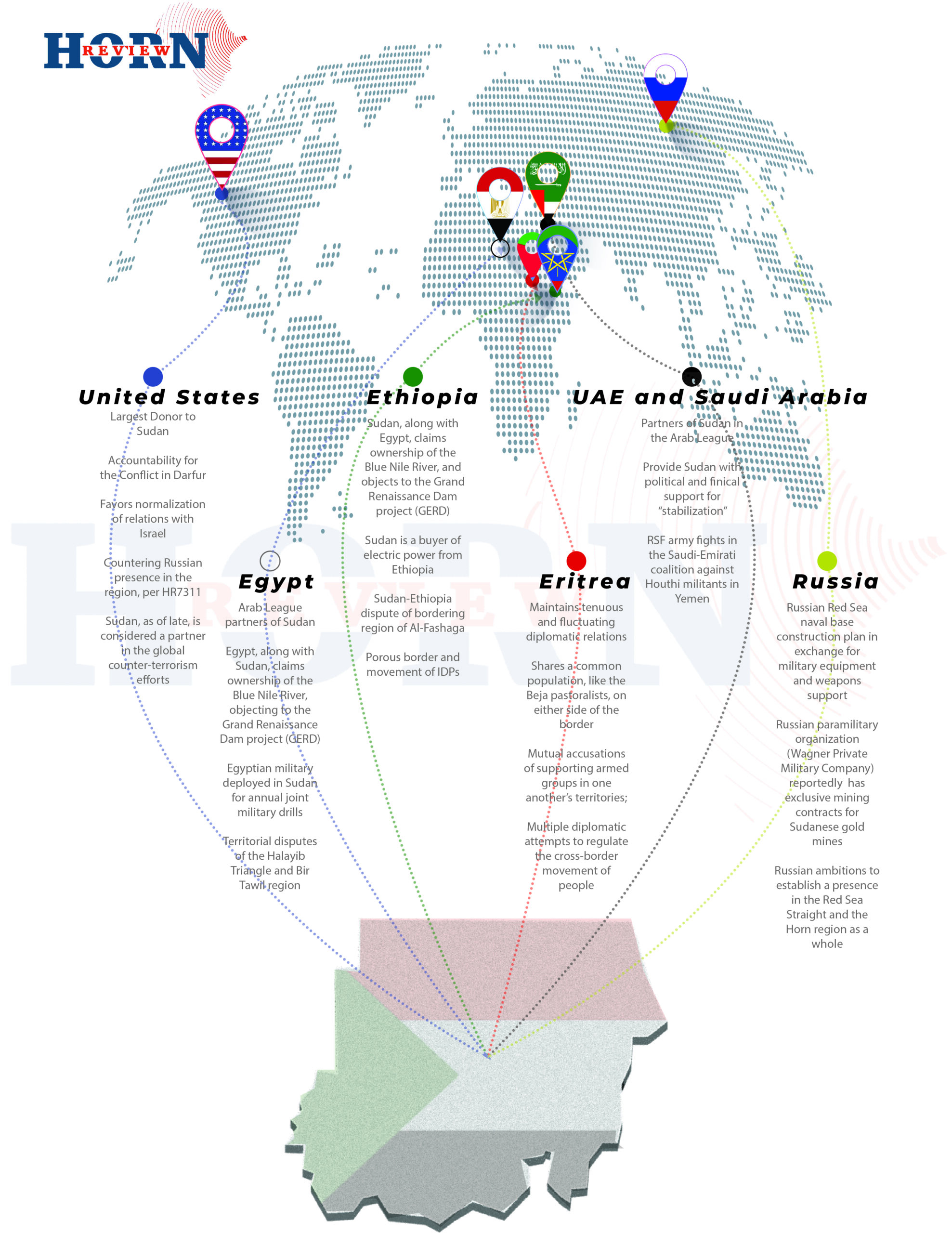

With a full-scale war being fought in urban centers, foreign states swiftly evacuating their nationals, depletion of food and basic necessities in conflict zones, and no apparent pathways for a return to peaceful political resolution, the humanitarian crisis in Sudan is progressively worsening with each passing day. A multitude of factors further heightens the complexity of this conflict: the multiplicity of external actors and interests, the direct involvement of neighbors like Eritrea and Egypt- and others in the Gulf Region- and the internationalization of the conflict among global actors like the US and Russia. These factors further weaken the role and position of regional actors and mechanisms like Ethiopia, the AU, and IGAD to spearhead diplomatic options for the political resolution of the conflict as they have in the past.

However, Ethiopia is the best-suited country in the region to play a decisive role if not in the political de-escalation between the military factions, and the amelioration of human conditions, particularly in mitigating the human toll as a result of the conflict. Tens of thousands of refugees have already fled the conflict via Chad, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Saudi Arabia; the latter via Port Sudan. Neighboring countries and humanitarian organizations are struggling to match the pace and urgency of the mounting humanitarian needs.

The route from Khartoum to Metemma is arguably the safest and most direct route to safety from the capital – given that the majority of this route is under the control of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) -particularly the route stretching from Gedaref to Metemma.

As a nation with a past mediatory role and close acquaintance with both parties to the conflict: Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (Hemmeti), Ethiopia is best positioned to be an interlocutor to facilitate humanitarian assistance. It is therefore essential for Ethiopia to consider forwarding itself as a principal country of asylum for Sudanese civilians fleeing the conflict and consider convening international partners to formulate a coordination mechanism to facilitate refugee reception and welfare measures.

This option might include:

-

- Establishment of a temporary reception center at Metemma with accommodation and essential care and services for arrivals;

- Application of expedited entry procedures for genuine asylum seekers;

- Coordination with the ICRC, UN, and both the SAF and the RSF leaderships to facilitate the movement of humanitarian convoys traveling between Khartoum and Mettema, and Metemma and Gedaref;

- Possible coordination with SAF to ensure security along the Gedaref-Metemma route.

Ethiopia is undoubtedly one of the countries to be directly and indirectly affected by the conflict; as it maintains the convening power within IGAD and the AU, Addis Ababa is therefore well positioned to promote, facilitate, and host multilateral diplomatic initiatives with the principal aim of aiding the Sudanese people and preventing a humanitarian calamity from unfolding.

Share

From Security Provider to a Security Vaccum? The Hasty Withdrawal of Ethiopia’s Decade-Long Peacekeeping Mission in UNISFA

From Security Provider to a Security Vaccum? The Hasty Withdrawal of Ethiopia’s Decade-Long Peacekeeping Mission in UNISFA

By: Kaleab Tadesse Sigatu1

Introduction

Ethiopia has been participating actively in UN peacekeeping missions since the 1950s up to now. The reasons were based on the sending regime’s intention, the nature of the armed forces, and the focus area of the deployment. The Imperial Ethiopian Government under Emperor Haile Selassie I (1930–1974) sent peacekeeping troops to Korea, Congo, and to the contested region of Jammu and Kashmir of India and Pakistan. The socialist military regime (1974–1991) did not participate in any peacekeeping missions at all. The post-1991 Ethiopian Government mostly focused on peacekeeping missions in Africa and contributed peacekeepers to Rwanda, Burundi, Liberia, Côte d’Ivoire, Central African Republic, Chad, Mali, Sudan, South Sudan, Somalia, and also in Haiti, and Yemen. Lastly, the new reformist government, which came to power in 2018, has made no policy change from the aforementioned regime toward participating in peacekeeping missions.

The Ethiopian National Defence Forces (ENDF) therefore acquired a paramount peacekeeping capability with the regional standard in training and experience gained through previous international peacekeeping deployments. This resulted in Ethiopia playing an important role in regional stability as the prevalent contributor to UN and AU peacekeeping missions, especially in Somalia, South Sudan, and Sudan.2 Even though Ethiopia’s military (peacekeeping) and peace mediating role is not without criticisms it became “a formidable force for peace, security, and stability in the Horn of Africa, and in Africa in general”.3 This is especially true concerning Ethiopia’s interventionist role in Somalia.4 Ethiopia’s first unilateral action in Somalia was in 1995 to remove the Islamic insurgent, Al-Ittihad Al-Islamiya (AIAI). In 1998 Ethiopia launched a second military intervention at the time of the Ethiopia–Eritrea war, following Eritrea’s effort – in collaboration with a Baidoa-based Somali warlord Hussein Aideed and involving the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) and the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) to open a second front.5 Ethiopia’s third intervention was in 2006, against the threat from the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) and supporting the Somali Transitional Federal Government. Lastly, Ethiopia joined AMISOM in 2014, simultaneously deploying troops outside the AMISOM command to support its troops under AMISOM.

Likewise, Ethiopia has been a part of the peacekeeping missions in Sudan and South Sudan for more than a decade. Ethiopia contributed police personnel for the United Nations Mission in Sudan (UNMIS) from 2005 until the independence of South Sudan in 2011. It is also a part of the United Nations Mission in the Republic of South Sudan (UNMISS), which is still optional since 2011. Since joining in 2014 Ethiopia has contributed around 2,000 troops to UNMISS making it one of the top five largest contributors.6 It also contributed around 20,000 mainly continent troops, in different rotations for the African Union–United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID), (2007–2020) in Sudan.7 Moreover, Ethiopia contributed the entire contingent troops to the United Nations Interim Security Force in Abyei (UNISFA), at the disputed border region between South Sudan and Sudan, which is the focus of this paper and discussed below. All missions make Ethiopia a ‘security provider’ in most of the conflict regions in the African continent, which is compounded by intra-regional and international intervention.8

South Sudan and Sudan and the conflict over Abyei

The north–south conflict in Sudan was between the mostly desert, largely Muslim and culturally Arabic North Sudan and the tropical, largely Christian or animist and culturally sub-Saharan Southern Sudan. The first Sudanese civil war happened between 1955 and 1972; it begins before the independence of Sudan from the Anglo– Egyptian colony and ended at the signing of the Addis Ababa Accord, an agreement that gave Southern Sudan autonomy, signed in Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia. However, in 1983, the government enforced Shari’a law on the south when President Nimeiry declared all of Sudan as an Islamic state, terminating the autonomous status of Southern Sudan, which triggered the second Sudanese civil war.9 It was the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) signed in 2005 that ended the civil war.

The CPA was signed between the government of Sudan and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLM/SPLA) after having continuous negotiations since 2002 under the auspices of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development(IGAD) and the government of Kenya.10 The CPA established a six-year interim period during which the southern Sudanese will have the right to govern affairs in their region; one of the major agreements of the CPA was the fact that Southern Sudan will have the right to vote for the referendum. The other CPA agreement was the resolution of the contested border region of Abyei, which gave Abyei special administrative status during the interim period. At the end of the six-year interim period, Abyei residents will vote in a referendum either to maintain special administrative status in the north or to become part of the south. The government of Sudan and SPLM/SPLA also agreed to share oil revenues from Abyei, to be split between the north and south with small percentages of revenues allocated to other states and ethnic groups.11

Consequently, South Sudan separated from northern Sudan and became an independent state after six years as per the agreement of the CPA on 9 July 2011. However, the demarcation of the border of the oil-rich Abyei region between South Sudan and Sudan became contentious because both states claimed it as their own territory.12 In addition, the South Sudanese referendum did not take place in Abyei because both sides failed to put it into practice, as they could not agree on who was eligible to vote.13

Political scientists argue that there is a likelihood of conflict between the secessionist or newly established and the former ‘mother’ state or rump on the territorial issue.14 This is true in the Horn of Africa in the case of Ethiopia and Eritrea and Somaliland and Puntland/Somalia. When a territory of a state breaks away and becomes an independent entity, the new land boundaries that emerge are often violently contested.

Jaroslav Tir in his study on interstate relations especially territorial disagreement between rump and secessionist states after a separation, put his argument as follows: Through the secession, the rump state has lost some of the territories it previously controlled to the secessionist state and may want a portion or all of it back. Conversely, the secessionist state may not be satisfied with how much land it has received and may desire even more of the rump state’s land. Finally, the secessionist state may set its sights on another secessionist state’s territory.

Land’s strategic value arises from its characteristics and/or location. Losing a high ground or an impenetrable swamp or desert may make the country easier to invade and thus undermine its defensive ability. Losing a piece of land containing resources such as ore deposits, ports, and so on undermines the rump state’s economic, and, by extension, military, capability. The desire of countries to pursue power is one of the cornerstones of the realist school of thought, and at least some realists view the role of territorial control as crucial to a state’s power.15