11

Nov

The Making of Darfur’s Periphery: Colonial Legacies and the Risk of Sudan’s Partition

Before its incorporation into the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, Darfur was an independent and well-established sultanate. Founded in the 17th century by the Keira dynasty, the Sultanate of Darfur had developed a complex political system centered around the Fur people. Its capital, Al-Fashir, was both an administrative and trading hub linking central Sudan to western and central Africa. Darfur’s autonomy remained largely intact until the late 19th century when the region became entangled in the larger imperial rivalries that swept across Africa. While much of Sudan came under Mahdist control in 1885, Darfur maintained a measure of independence, ruled by Sultan Ali Dinar from 1898 onward, who sought to preserve Darfur’s sovereignty amid the shifting imperial landscape.

Darfur was officially incorporated into the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan in 1916, during World War I. The British saw Sultan Ali Dinar as a potential threat because of his open sympathies with the Ottoman Empire, which was then at war with Britain. With his death after a war with Britain, the Darfur Sultanate ceased to exist, and the region was annexed into the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan as the “Province of Darfur.”

However, this annexation was less an integration than an occupation. The colonial administration treated Darfur as a frontier region remote, underdeveloped, and of little economic value. It was governed indirectly through tribal chiefs under the “Native Administration” system, which relied on local notables to maintain order and collect taxes. This indirect rule preserved tribal hierarchies but also froze ethnic divisions and entrenched inequalities between groups such as the Fur, Zaghawa, Berti, and Arab pastoralists.

The authorities at that time invested little in Darfur. Infrastructure, education, and health services were concentrated in the Nile Valley, where the British and Egyptian administrators resided. Darfur remained isolated, connected to Khartoum only by long desert routes and minimal administrative contact. This isolation deepened economic disparities between western Sudan and the more developed central and northern regions.

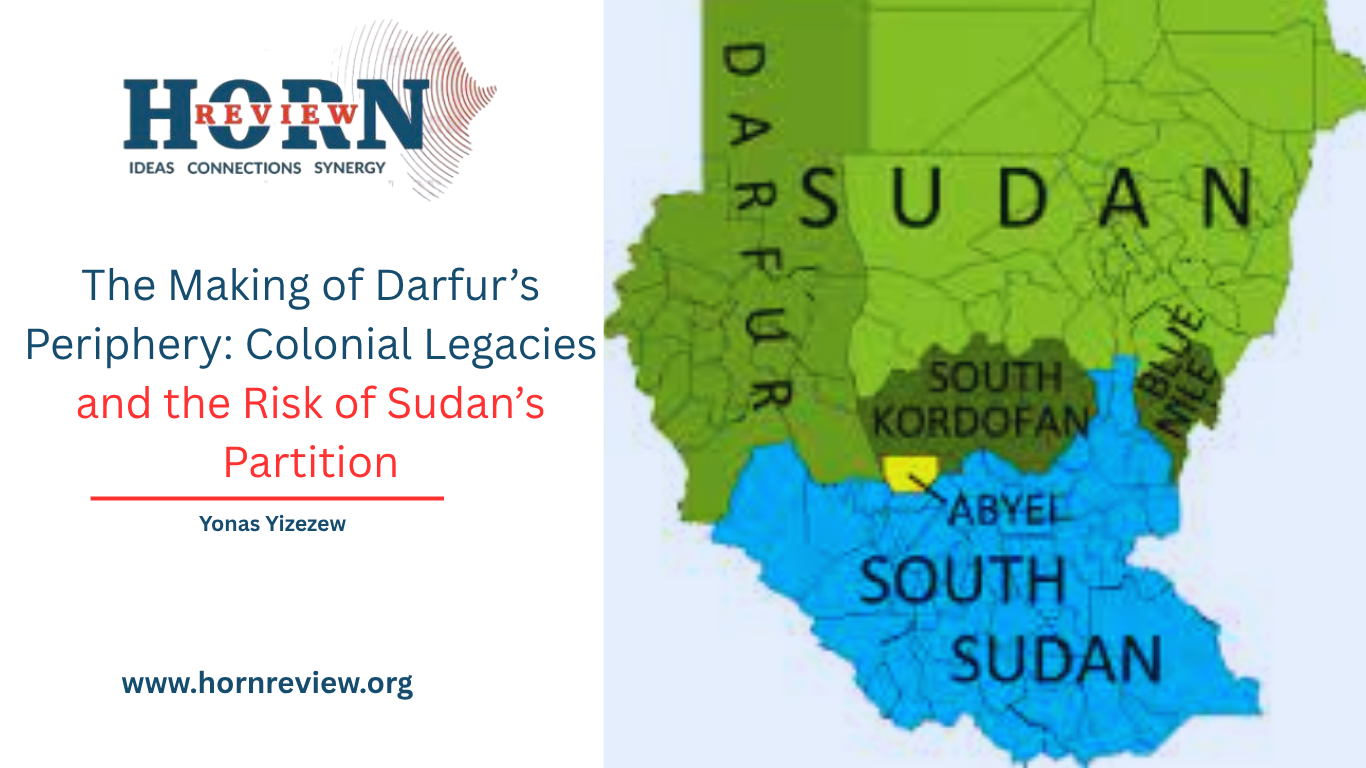

Politically, Darfur was excluded from the small elite that emerged in Khartoum and Omdurman, an elite that would later dominate Sudanese politics after independence. The colonial legacy thus created a two-tiered Sudan: a “core” centered along the Nile with access to power, education, and economic resources, and a “periphery” encompassing Darfur, Kordofan, and southern Sudan, left underdeveloped and politically voiceless.

By the 1940s and 1950s, as nationalist movements gained strength across Africa, the question of Sudanese independence grew. But Darfur remained largely detached from these developments. The Sudanese nationalist movement dominated by riverine Arab elites did not include representatives from Darfur or other peripheral regions.

As Sudan approached independence in 1956, Darfur’s political structures were still governed through tribal authorities rather than modern administrative institutions. The absence of educational infrastructure meant that Darfur produced few of the educated elites who could participate in the emerging national bureaucracy or political parties. When independence came, power was thus monopolized by northern and central Sudanese politicians. Darfur was already a marginalized region, economically poor, politically isolated, and socially divided. The seeds of later conflict were sown during this era, as competition over scarce resources and historical grievances festered in a region that felt forgotten.

Because Darfur lacked a political class integrated into the Khartoum elite, successive governments ruled it through security-focused bargains: co-opt local strongmen, arm allied militias, and deploy military solutions rather than development. This was facilitated by the colonial habit of outsourcing local order to chiefs and militias. In the 1980s–2000s, the central state recruited and armed Arab militias (the Janjaweed) to suppress non-Arab insurgencies. These militias drew on networks of patronage that traced a line to the colonial era’s emphasis on indirect control and on the post-colonial state’s preference for militarized, low-cost governance in the periphery.

The militias that became the Janjaweed in early 2000s and notorious during the 2003 Darfur war, were later reorganized and formalized into the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in 2013. The RSF’s leadership and recruitment drew on the same local actors, frontier logics and patronage networks that colonial indirect rule had helped fix. The categories that were administratively useful to colonial officers as “Arab” vs “African,” pastoralist vs farmer have been politically weaponized. When militias or state actors wish to seize land or settle scores, they use those labels to mobilize recruits. That institutional continuity is crucial as a force born from locally armed militias whose use had been normalized by state practice, now operates as a national paramilitary actor with political ambitions. The RSF’s domination of much of Darfur after 2023 is therefore not an ex nihilo event but a recirculation of a century-old pattern.

Between 2013 and 2023, the RSF evolved from a government-backed counterinsurgency force into an autonomous political and economic actor. Under Omar al-Bashir, it was used to suppress rebellions in Darfur, South Kordofan, and Blue Nile, but its growing control over gold mines and border trade gave it independent financial and military power. The 2019 uprising and the fall of Omar al-Bashir accelerated that political ascent as RSF leaders translated battlefield leverage into formal roles in the transitional authorities, embedding paramilitary influence inside the state rather than keeping it at the margins. Tensions between the RSF and the regular army then hardened after the 2021 coup and turned into open struggle in April 2023. What appeared to be integration was, in practice, the quiet emergence of a parallel army rooted in Darfur yet operating as a national force, setting the stage for the confrontation that erupted in 2023.

After the war erupted, Darfur quickly emerged as a central arena of contestation. The reasons are structural since Darfur’s fragile state institutions, entrenched patronage systems, and the RSF’s historic social base created a political environment where authority itself became a prize of war. The collapse of governance exposed the unresolved power hierarchies that had been sustained since the colonial period through indirect control and local militarization. What is unfolding is that the RSF seeks to translate its local dominance into administrative legitimacy.

The claim that the fall of al-Fashir to the RSF in October 26, 2025 has transformed a long standing pattern of contested control into a concrete axis of power. The RSF’s dominance across Darfur now represents a clear form of territorial consolidation that brings the likelihood of a de facto partition. By controlling Darfur’s main towns and rural routes, the RSF has turned the region into a distinct political and administrative sphere, detached from the Nile Valley where the army and the remaining state institutions are concentrated. This separation reflects the emergence of two competing centers of power, one rooted in Khartoum’s military bureaucracy and another grounded in Darfur’s paramilitary networks, each claiming authority over its own territory and population. The RSF’s capture of Darfur’s capitals and its entrenchment in the countryside have already created the conditions of parallel governance that look very like the segments of the old colonial project come alive again.

Seen through the historical frame, the current risk of partition looks less like a sudden failure of modern politics and more like the reappearance of an older spatial logic. The colonial choices created administrative cleavages that turned peripheral regions into quasi separate zones of rule. That design gave rise to patterns of delegated sovereignty, weak institutions and militarized local authority. When violent collapse removed the last effective central integrative mechanisms, those old separations became usable again. In this respect a partition of Sudan would not be a novel invention so much as a return to a fragmented geography whose outlines were first drawn under imperial rule.

By Yonas Yizezew, Researcher, Horn Review