8

Dec

The Unravelling of the Haile Selassie–Nimeiry Pact and the Rise of a Weaponized Frontier

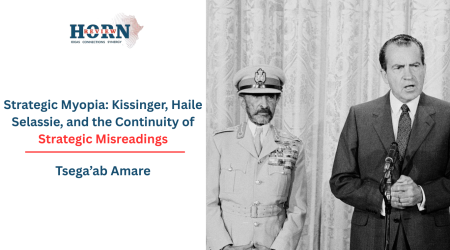

The sixteen-year rule of Gaafar Nimeiry (1969–1985) represents more than a chapter in Sudanese history; it defines the structural genesis of modern conflict in the Horn of Africa. Nimeiry’s tenure was characterized by a profound ideological flux, mirroring Sudan’s precarious position as the strategic nexus between the Arab world and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Rather than incoherence, Nimeiry’s foreign-policy shifts, from socialism to staunch anti-communism and eventually to radical Islamization, were rooted in a persistent search for regime security amid rapidly shifting domestic and external pressures.

From the initial 1969 “May Revolution” to his 1985 ouster, Nimeiry navigated the complexities of the Cold War, transitioning from Soviet client to Western bulwark. Nowhere, however, were these shifts more consequential than in Sudan’s relationship with Ethiopia. The move from Haile Selassie’s cooperative diplomacy to the militarized posture of the Derg fundamentally reshaped the regional security architecture.

To understand the magnitude of the rupture that occurred after 1974, it is essential to revisit the brief period of transactional stability that preceded it. In the early 1970s, Emperor Haile Selassie, whose leadership carried considerable moral weight within Africa, pursued an outward-looking foreign policy designed to insulate Ethiopia from external support for domestic insurgencies. This logic informed his crucial role in mediating Sudan’s First Civil War, culminating in the 1972 Addis Ababa Agreement (AAA).

Though celebrated for ending nearly two decades of civil conflict and granting autonomy to Southern Sudan, the agreement was also a pragmatic security arrangement: Ethiopia would help stabilize Sudan, and in return Sudan would restrict cross-border activities of Eritrean insurgents, which was utilizing Sudanese territory as a logistical sanctuary. For a brief window, the Addis Ababa Consensus effectively educed border militarization. However, this stability was contingent upon the survival of the two incumbent regimes. When the imperial order in Ethiopia collapsed in 1974, the security guarantees collapsed with it.

The rise of the Derg and its swift realignment toward the Soviet bloc introduced a stark ideological divergence between Addis Ababa and Khartoum. Mutual suspicion replaced the earlier climate of cooperation. Nimeiry, who had already survived a pro-Soviet coup attempt in 1971, accelerated his strategic reorientation, first toward China and eventually toward the United States and its regional partners. This repositioning made Sudan an increasingly important actor in the Western containment architecture.

Concurrent with his pivot to the West, Nimeiry pursued what can be termed an Arab Extension strategy to shore up his regime’s economic and political foundations. Facing internal opposition from varied factions, Nimeiry sought to anchor Sudan within the conservative Arab mainstream, forging close ties with Saudi Arabia and other Gulf monarchies. This move was designed to secure the financial liquidity necessary to maintain his patronage networks and military apparatus.

This strategy reached its most controversial zenith when Nimeiry, among a very small number of Arab leaders, maintained close relations with Anwar el-Sadat after the Camp David Accords. While this decision alienated Sudan and much of the Sudanese public from the radical Arab states, it solidified his value to the United States and Egypt, confirming him as a “reasonable, politically seasoned personality.” This paradox illustrates Nimeiry’s consistent prioritization of regime security and Western alignment over rigid Pan-Arab ideological purity. The pursuit of this ‘Arab extension’ provided the essential external economic cushion required to engage in what would become the defining feature of his foreign policy: the proxy war with Ethiopia.

The collapse of the Selassie-Nimeiry consensus led to the weaponization of borders, a phenomenon where the governance of the frontier was deliberately abandoned in favor of utilizing refugee flows and insurgents as instruments of statecraft. The conflict between Nimeiry’s Sudan and the Derg’s Ethiopia evolved into a symmetrical war of reciprocal subversion.

The Marxist regime in Ethiopia, seeking to destabilize its pro-Western neighbor, provided extensive support to the budding Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A). Following the mutiny of Southern soldiers in 1983, the Derg offered training centers (such as Pinyudo and Itang), weaponry, and radio facilities to John Garang’s forces. This aggressive externalization of conflict forced Khartoum to divert immense resources to its internal southern front.

In response, Nimeiry allowed Sudan to function intermittently as an important logistical node and sanctuary for the Ethiopian armed opposition. Sudan’s support for the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) was not driven by a genuine commitment to their revolutionary ideals, but by the need for leverage against the Derg.

The mechanism of this support was the refugee crisis. The influx of Eritrean and Tigrayan refugees fleeing the Derg’s ‘Red Terror’ provided the perfect operational cover. Nimeiry’s regime allowed the EPLF and TPLF to utilize vast refugee camps in Eastern Sudan as headquarters, recruitment grounds, and transit points for arms pipelines. This relationship was highly transactional; Sudan provided cross-border sanctuary and intelligence sharing, enabling these groups to survive the Derg’s mechanized offensives. While Nimeiry would occasionally curtail this support during brief periods of détente, the pipelines were consistently reactivated whenever tensions with Addis Ababa flared.

Nimeiry’s foreign policy was a masterclass in short-term survival at the expense of long-term state viability. By 1983, the contradictions of his Strategic Ideological Pivots came home to roost. In a desperate Third Pivot to secure domestic legitimacy against growing Islamist influence, Nimeiry imposed Sharia law and abrogated the Addis Ababa Agreement, the very document that had anchored his early success.

This decision provided the SPLM/A with the moral and legal justification to launch the Second Sudanese Civil War, this time with full backing from the Derg. Nimeiry’s attempt to use the Arab Extension via Islamization to save his regime ultimately destroyed the national unity that the African protection era had briefly secured.

The legacy of this era is profound. While Nimeiry was overthrown in 1985, the proxy infrastructure he built remained. Sudan’s logistical support was instrumental in the eventual victory of the EPLF and TPLF over the Derg in 1991, reshaping the map of the Horn of Africa and birthing an independent Eritrea.

However, the reciprocal subversion model, the belief that one’s own security is best achieved by arming the neighbor’s rebels, became an entrenched norm in the region’s diplomatic DNA. The weaponized border, first engineered during the clash between Nimeiry and the Derg, remains the primary theater of conflict in the Horn of Africa today.

By Tsega’ab Amare, Researcher, Horn Review