5

Jun

Repatriation’s Dual Legacy: Exclusion, Justice, and the Struggle for Black Agency

For many descendants of enslaved Africans, the notion of “repatriation” carries a deeply personal and bittersweet resonance – a longing to reclaim what was violently taken away. Yet, for others, notably the 19th-century proponents of the American Colonization Society (ACS), repatriation was a paternalistic instrument aimed at expelling free Black Americans and preserving a white supremacist social order.

Across centuries, the concept of repatriation has been weaponized, redefined, and reclaimed within racial politics, reflecting a persistent tension between exclusion and justice. From the ACS’s 19th-century campaign to relocate free Black Americans to Africa, to the Caribbean Reparations Commission’s (CRC) contemporary call for a voluntary “right to return” as part of reparatory justice, these movements – while superficially similar – diverge sharply in intent. One sought to erase Black presence; the other strives to restore agency and dignity. This dichotomy echoes into modern political discourse, particularly in Donald Trump’s migration rhetoric, which revives exclusionary logics adapted to 21st-century realities. Examining these historical and contemporary trajectories reveals that repatriation, when divorced from the agency of marginalized communities, perpetuates injustice, whereas reparations frameworks rooted in self-determination offer pathways toward systemic equity.

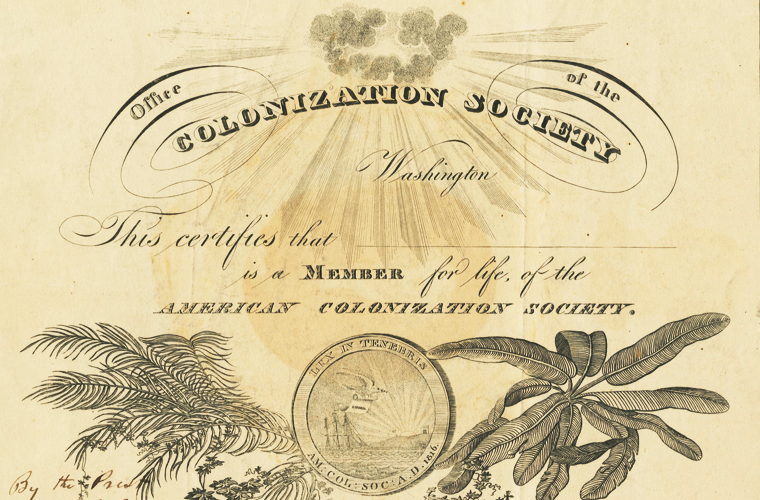

The ACS, established in 1816, emerged from a blend of white supremacist anxieties and paternalism. Its mission – to relocate free Black people to Liberia – was framed as a “solution” to the “problem” of racial coexistence in a society predicated on chattel slavery. Slaveowners feared that free Black communities would inspire rebellion, while Northern elites doubted the feasibility of racial integration. Though figures like Paul Cuffee initially supported emigration as a form of self-determination, the ACS faced widespread opposition from Black leaders who asserted that America belonged to Black people as much as to whites. Frederick Douglass famously denounced the ACS as a racist scheme designed to preserve slavery by exiling potential allies of the enslaved. The ACS’s vision of repatriation was exclusionary at its core, prioritizing white supremacy over Black citizenship. By 1867, fewer than 15,000 Black Americans had migrated to Liberia – a testament to the widespread rejection of coerced exile. The ACS’s legacy underscores a crucial lesson: solutions imposed without centering marginalized voices entrench oppression rather than alleviate it.

In stark contrast, the Caribbean Reparations Commission (CRC), spearheading a movement since 2013, reclaims repatriation within a broader framework of justice and empowerment. In the postcolonial and globalized era, the CRC’s 10-point plan calls not merely for financial reparations but for cultural restoration, debt relief, and a voluntary right of return to Africa. This approach situates the transatlantic slave trade as a crime against humanity, demanding moral and legal accountability from former colonial powers. Unlike the ACS’s expulsionist agenda, the CRC’s vision of repatriation is predicated on development aid, dual citizenship, and support structures to enable successful reintegration, challenging the outdated notion that Black people unable to thrive in the Americas would somehow flourish in Africa without assistance. Central to the CRC’s argument is the historic injustice of compensating slaveowners – Britain’s 1835 payment of £20 million, equivalent to 40% of its national budget – while denying reparations to the enslaved. The CRC contends that this imbalance persists today, manifested in poverty, structural racism, underdevelopment, health disparities, and cultural erosion across the Caribbean. Opposition to reparations often rests on legalistic technicalities that perpetuate collective amnesia, ignoring these enduring legacies.

The exclusivist framework of the ACS finds troubling echoes in the rhetoric and policies of Donald Trump’s administration. Though operating in a vastly different context – post-Civil Rights America grappling with globalization and economic anxieties – Trump’s migration policies perpetuate racialized exclusion. His infamous 2018 “shithole countries” remark dismissed African nations while privileging immigrants from predominantly white countries like Norway, reflecting an implicit racial hierarchy reminiscent of the ACS’s logic. Trump’s administration suspended refugee programs while expediting visas for white South African farmers, mirroring the ACS’s preference for racial homogeneity but adapted to modern geopolitical and economic contexts. Whereas the ACS sought to physically remove free Black Americans, Trump’s policies selectively target migrants from majority-Black and brown nations within a globalized labor market. Furthermore, Trump’s unfounded claims that immigrants “steal jobs” or threaten national security echo scapegoating narratives that disguise systemic economic dislocation. These narratives mirror the ACS’s fear of free Black labor competing with white prosperity in an agrarian economy, now transformed into anxieties over deindustrialization and wage stagnation under neoliberal economic structures. These parallels reveal how racial exclusion adapts fluidly to shifting economic and political landscapes.

The CRC’s reparations framework, bolstered by the African Union’s support, offers a transformative alternative to such exclusionary discourses. Its emphasis on apology, cultural restoration, and self-determination embodies a reparative justice model rooted in the agency of those most affected. Unlike the ACS’s paternalistic impositions or Trump’s top-down policy maneuvers, the CRC’s legitimacy stems from grassroots origins and a collective demand for systemic redress. The African Union’s collaboration with CARICOM symbolizes an international commitment to confront historic exploitation and reject exclusionary practices in favor of equity.

The contrasting legacies of these movements illustrate the ongoing contestation over belonging and justice. While the ACS and Trump-era policies differ in historical context and form – slavery versus globalization, overt versus covert racism – their shared logic of racialized exclusion persists, underscoring the tenacity of white supremacy. When repatriation is wielded as a tool of control, it sustains hierarchical power structures. Conversely, when articulated as a voluntary right embedded in reparatory justice, it becomes an instrument of empowerment and transformation. The CRC’s comprehensive approach – centered on apology, cultural restoration, and systemic change – avoids the pitfalls of the ACS’s legacy and offers a model for contemporary struggles.

As global debates around migration and justice intensify, the enduring lesson remains: lasting solutions must center the voices of marginalized communities and confront the legacies of segregation. The failures of the ACS and the ongoing efforts of CARICOM remind us that true repair, not removal, is the path toward equity and reconciliation.

By Surafel Tesfaye,Researcher,Horn Review