13

Jan

How Saudi Arabia Is Reasserting State Power in Sudan and Yemen?

The return of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) to Khartoum in January 2026 was not a sudden battlefield miracle, nor was it the product of internal Sudanese dynamics alone. It was the culmination of a long, externally enabled campaign that mirrors almost point for point what Saudi Arabia has simultaneously executed in Yemen. When viewed together, Sudan and Yemen reveal parallel conflicts shaped by the same regional logic Saudi Arabia’s determination to restore central state authority, marginalize UAE-backed sub-state actors, and reclaim strategic influence along the Red Sea.

In Sudan, the SAF’s recovery began from a position of structural weakness. By mid-2024, the army was overstretched; suffering from severe manpower shortages and losing ground to the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), whose decentralized structure and predatory control over territory gave it short-term battlefield advantages. The SAF’s response was not merely military but political and social. It began integrating allied forces that had previously stood outside the regular army, most notably the Darfur Joint Forces a coalition of former rebel groups with intimate knowledge of western and central Sudan. These forces played a decisive role in holding El Fasher and disrupting RSF supply routes, preventing a complete RSF consolidation in Darfur.

At the same time, the SAF revived Islamist paramilitary units such as the Al-Baraa Ibn Malik Brigade. This was not ideological romanticism but a pragmatic decision driven by necessity. These units brought manpower, cohesion, and combat experience at a moment when the SAF needed loyal fighters willing to hold ground in urban warfare. The army also introduced a broad amnesty program for RSF defectors, transforming the conflict from a binary confrontation into a contest over allegiance.

That strategy reached a critical turning point in October 2024 with the defection of Abu Aqla Kaikal. Kaikal was not a marginal figure; he commanded the Sudan Shield Forces and had been one of the RSF’s most valuable assets in central Sudan. His forces had deep ties across al-Jazirah, Sennar, and the al-Butanah region and they had played a key role in RSF victories earlier in the war. When Kaikal switched sides, it shattered RSF momentum in the center of the country. More importantly, it signaled that the SAF was once again becoming the winning side a perception that triggered further local realignments.

By early 2025, the SAF was no longer fighting a war of attrition in every neighborhood. Through amnesty, co-optation, and selective offensives, it steadily eroded the RSF’s local support base. This made the eventual push into Khartoum less about total destruction and more about political isolation. When the government formally returned to the capital in January 2026, it was the endpoint of a process in which alliances mattered as much as firepower.

Saudi Arabia’s role in this transformation was decisive. Riyadh provided the financial and logistical backing that allowed the SAF to sustain operations from Port Sudan, secure Red Sea access, and reorganize its forces. This support extended beyond immediate battlefield needs. The emerging Pakistan–Sudan arms procurement arrangement including drones and aircraft intended to consolidate SAF control is widely understood to be financially underwritten by Saudi Arabia, reflecting Riyadh’s preference for indirect military enablement rather than overt deployment. The funding structure mirrors Saudi behavior elsewhere: outsourcing hardware while retaining strategic leverage.

Saudi diplomatic backing consistently reinforced the SAF’s legitimacy while rejecting the RSF’s attempt to form a parallel government in mid-2025. This external support gave the SAF both material depth and political confidence the ability to plan offensives without fear of international isolation or financial collapse.

Importantly, Saudi Arabia did not begin the Sudan war as a military patron. In the early phases of the conflict, Riyadh pursued a primarily diplomatic track, positioning itself as a mediator and leveraging Sudan to strengthen its standing within the Arab League and improve its working relationship with Washington. This approach was calculated and reputationally conservative. However, as UAE influence expanded through alleged arms flows and political backing to the RSF, Saudi diplomacy proved insufficient. Riyadh’s re-entry into Sudan shifted from diplomatic management to material intervention mirroring, in indirect form, the very tactics it accused the UAE of using.

What makes Sudan especially significant is that the same Saudi logic was unfolding, almost simultaneously, in Yemen but in a more overtly military form.

By late 2025, Saudi Arabia had concluded that the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council (STC) had become a strategic liability. The STC’s control of southern ports, its separatist agenda, and its willingness to operate independently of the internationally recognized government posed a direct challenge to Saudi Arabia’s vision of a unified Yemeni state aligned with Riyadh’s security interests. When the STC launched “Operation Promising Future,” Saudi Arabia responded not with mediation but with force.

On December 30, 2025, Saudi-led forces struck Emirati vessels in Mukalla that were allegedly supplying the STC with weapons. This was a clear escalation and a message. Within days, Saudi-backed government forces launched a coordinated offensive, retaking Hadhramaut and Al-Mahra and entering Aden by January 7, 2026. The speed of the collapse was striking. On January 9, the STC announced its dissolution, and its leader, Aidarous al-Zubaidi, fled to the UAE.

Just as in Sudan, Saudi Arabia followed military action with institutional consolidation. A Supreme Military Committee was established under coalition oversight to unify fragmented forces, and Riyadh convened Yemeni factions to shape a Saudi-managed political process. The objective was clear: eliminate parallel authorities, dismantle sub-state power centers, and restore a single chain of command.

Saudi red lines in Yemen were drawn first and enforced militarily, but they did not stand alone. Egypt, facing its own border security imperatives, has simultaneously articulated firm red lines in Sudan. For Cairo, the survival of the Sudanese state is inseparable from Egyptian national security. This convergence has made Egypt a natural enabler of Saudi strategy. While Saudi Arabia provides financial depth and diplomatic cover, Egypt supplies institutional legitimacy, military signaling, and if required the willingness to escalate overtly. The Saudi-led effort is therefore not unilateral but reinforced by Egyptian strategic alignment.

The parallels between Sudan and Yemen are not accidental. Both countries entered 2026 as de facto divided states. In Sudan, the SAF controls the east and center while the RSF remains entrenched in parts of Darfur. In Yemen, authority is split between the Houthis in the north and the Saudi-backed government in the south. In both cases, UAE-aligned actors attempted to formalize fragmentation through parallel governance structures the RSF’s “peace government” in Sudan and the STC’s southern administration in Yemen.

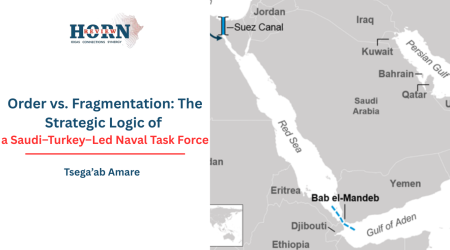

Saudi decision-makers increasingly assess that Emirati actions particularly the entrenchment of parallel authorities risk locking both countries into permanent geopolitical division. Such outcomes would expose Saudi borders, undermine Red Sea maritime security, and create long-term instability adjacent to Vision 2030’s economic corridors. The response has therefore emphasized containment and diversification, culminating in the formation of what regional analysts now describe as a “New Red Sea Axis.”

By 2026, this emerging axis brings together Saudi Arabia as convener, with Egypt and Turkey as northern anchors and Sudan, Somalia, and Eritrea as southern littoral partners. Described as a “Coalition of the Status Quo,” this alignment seeks to restore recognized state authority rather than empower militias, councils, or commercial proxies. For the first time since 2014, the Red Sea geopolitical map appears simplified not stabilized, but clarified.

Yet this transition remains deeply fragile. In western Sudan, the RSF continues to consolidate control over parts of North Darfur following the fall of El Fasher in October 2025. By exploiting gold revenues and supply corridors through Libya and Chad, the RSF retains the capacity to spoil any national settlement. The de facto partition of Sudan SAF east, RSF west remains a durable reality that the proclaimed “Year of Peace” must confront rather than obscure.

It would therefore be premature to frame current developments as a definitive Saudi victory or to assume Emirati acquiescence. The UAE retains asymmetric tools and the capacity for unexpected counter-moves. What can be said with greater confidence is that Saudi Arabia is placing a high-stakes bet: that hegemonic restoration, when leveraged through institutional legitimacy, strategic depth, and aligned partners like Egypt and Turkey, can reverse fragmentation without triggering wider regional escalation.

Whether this situation produces sustained peace in Sudan and restored unity in Yemen or merely a reordered contest will define the next phase of Red Sea geopolitics.

By Surafel Tesfaye, Researcher, Horn Review