13

Jan

Order vs. Fragmentation: The Strategic Logic of a Saudi–Turkey–Led Naval Task Force

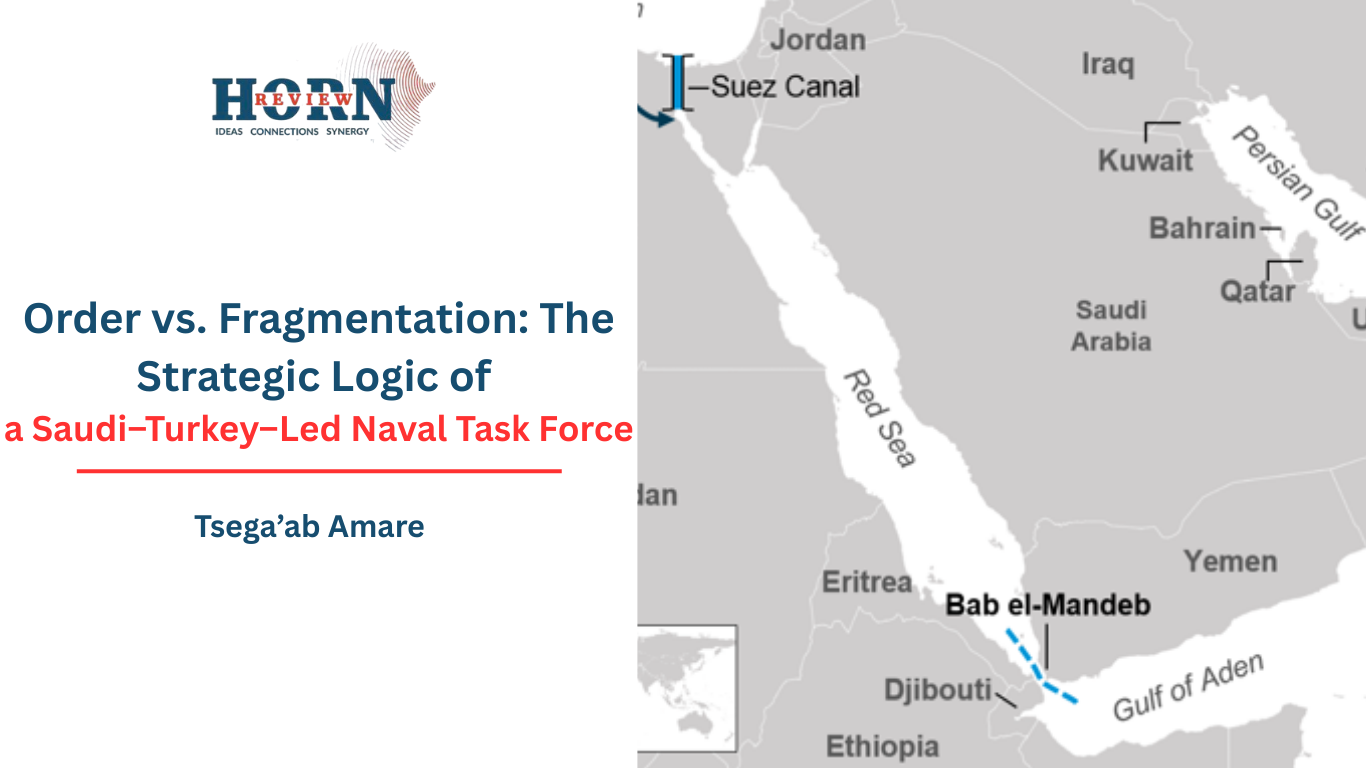

The convergence of Houthi maritime disruptions, the proliferation of state-supported secessionist movements, and a perceived vacuum in traditional Western-led security frameworks has necessitated an indigenous realignment along the Red Sea maritime corridor among regional middle powers. In early January 2026, reports and strategic assessments began to coalesce around a potential institutional response: the formation of a joint naval task force led by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Republic of Turkey.

This proposed ‘Red Sea Axis’ seeks to incorporate key littoral states, including Egypt, Djibouti, Somalia, and Sudan, and to function as a coalition of the status quo confronting a rival bloc of revisionist and fragmentation-oriented actors. Rather than an ideological alliance, the emerging framework reflects converging threat perceptions and material interests tied to sovereignty preservation, maritime commerce, and regional order.

The strategic foundation for the proposed task force was laid during the inaugural Turkey–Saudi Arabia Naval Forces Cooperation and Coordination Meeting held in Ankara on January 7, 2026. Hosted at the Turkish Naval Forces Command Headquarters, the meeting marked a decisive pivot away from the diplomatic turbulence of the previous decade toward structured military interoperability. Delegations from both countries reviewed maritime security challenges in the Mediterranean and the Red Sea, with particular emphasis on coordination, joint planning, and operational compatibility.

The participation of Rear Admiral Ilkay Cek, head of Turkey’s Naval Forces Planning and Resource Management Department, underscored the technical depth of the engagement. Discussions focused on mechanisms for joint exercises, planning integration, and the exchange of naval expertise, signaling a shift toward regional strategic autonomy. For Turkey, this alignment advances its Blue Homeland doctrine and protects its expanding investments in Somalia. For Saudi Arabia, this offers a capable partner to secure its extensive Red Sea coastline, which spans over 1,811 kilometers, against asymmetric and non-state threats.

A significant accelerator of the proposed naval task force is the potential expansion of the Saudi–Pakistan Strategic Mutual Defense Agreement (SMDA) to include Turkey. Signed in September 2025, the agreement contains a mutual defense clause stipulating that aggression against one party is to be treated as an attack on both. The inclusion of Turkey would transform the pact into a de facto trilateral security bloc rather than a formally amended treaty.

Such an arrangement would combine Saudi financial capacity, Pakistan’s strategic deterrence, and Turkey’s defense-industrial and maritime capabilities. Analysts argue that this configuration could possess sufficient weight to reshape the Red Sea security balance by strengthening collective deterrence against hostile non-state actors and supporting regional norm enforcement without direct reliance on Western command structures. The SMDA pact employs mutual defense language similar to NATO’s Article 5 and reflects Riyadh’s effort to diversify its security partnerships beyond the United States. In this context, an expanded arrangement including Turkey could gradually reduce dependence on U.S.-led initiatives, while stopping short of outright confrontation with existing international security frameworks.

While the Saudi–Turkish axis provides the financial and technological engine, the Arab Republic of Egypt functions as the operational anchor of the proposed task force. In September 2025, Egypt and Saudi Arabia signed a landmark naval cooperation protocol in Alexandria, institutionalizing joint maritime missions aimed at countering Houthi threats to Red Sea shipping.

The agreement was driven in part by Egypt’s acute economic pressures. Suez Canal revenues declined by more than fifty percent following the large-scale rerouting of global shipping around the Cape of Good Hope, costing Cairo billions in sustainable income. The agreement emphasizes regional leadership and reduced external dependency, designating Egypt’s and Saudi Arabia’s naval facilities as primary operational hubs for coordinated patrols in the Bab el-Mandeb and the Gulf of Aden.

Furthermore, for Cairo, embedding itself within Red Sea security arrangements also offers a means of indirectly shaping the Horn’s strategic balance, allowing maritime cooperation to reinforce its negotiating position in parallel disputes over Nile Basin governance and regional influence.

The most significant catalytic event accelerating Saudi–Turkish–Egyptian alignment was Israel’s formal recognition of the Republic of Somaliland on December 26, 2025. As the first United Nations member state to extend such recognition, Israel challenged the post-colonial borders of the Horn of Africa, which are safeguarded by the African Union’s principle of border inviolability.

This diplomatic move, reportedly facilitated by the United Arab Emirates and integrated into the broader Abraham Accords framework, was driven by Israel’s pursuit of strategic depth against Houthi missile and drone threats and the potential relocation of Palestinians. Israeli Foreign Minister Gideon Sa’ar’s visit to Hargeisa on January 6, 2026, reportedly included discussions on security cooperation and the potential future establishment of an Israeli military facility near the Bab el-Mandeb. Critics have characterized this emerging alignment as an “axis of secessionists” that leverages state fragmentation as a tool of regional influence.

The proposed naval task force must also navigate the increasingly adversarial relationship between Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. While once aligned, the two states now pursue divergent regional strategies. Riyadh prioritizes territorial integrity and state-centric governance, leading it to support internationally recognized authorities in Yemen and Sudan. Abu Dhabi, by contrast, has cultivated influence through southern secessionist actors such as the Southern Transitional Council, securing leverage over strategic ports including Aden, Berbera, and the Socotra archipelago.

In early January 2026, Saudi-backed forces reversed key Southern Transitional Council gains in southern Yemen, retaking control over critical infrastructure in Aden. Riyadh subsequently issued public warnings to Abu Dhabi, characterizing continued support for secessionist movements as a strategic red line. While Saudi Arabia frames its position as a defense of sovereignty, its selective tolerance of non-state partners in other theaters exposes contradictions that regional rivals continue to exploit.

The feasibility of a Saudi–Turkey-led naval force is reinforced by rapid advances in unmanned maritime and aerial systems. In 2023, Saudi Arabia signed a three-billion-dollar contract for the acquisition of Bayraktar Akinci unmanned combat aerial vehicles. By late 2025, Saudi naval and air force operators had completed training, and the platforms were integrated into maritime surveillance doctrines.

The Akinci provides extended persistence, with the ability to loiter over the Bab el-Mandeb for up to twenty-four hours, enabling continuous tracking of Houthi drone boats and fast-attack craft. When combined with Turkey’s naval presence in Somalia and Egypt’s Mistral-class helicopter carriers, the task force achieves layered surveillance and strike capacity that allows for sustained maritime operations independent of Western systems.

Beyond security considerations, economic imperatives play a central role in motivating the task force. Turkey’s engagement in Somalia has evolved from humanitarian assistance to strategic resource protection. In February 2026, Turkey is scheduled to begin offshore energy exploration using the ultra-deepwater drillship Cagri Bey, supported by Turkish naval escorts to deter piracy and militant sabotage.

Despite its stabilizing intent, a Saudi–Turkey-led naval task force risks accelerating bloc formation across the Red Sea and Horn of Africa, hardening regional alignments into competing security camps. By institutionalizing a “status quo coalition” in response to fragmentation-oriented actors, the initiative may inadvertently deepen polarization rather than dampen it, incentivizing rival powers to formalize counter-alignments and militarize their own partnerships.

For smaller littoral states, this dynamic could narrow diplomatic maneuverability, forcing alignment choices that entangle local security concerns within broader Gulf-Middle Eastern rivalries. Rather than insulating the Red Sea from external competition, the consolidation of such an axis may thus transform the maritime corridor into a structured arena of bloc confrontation, where stability is contingent not on inclusive regional mechanisms but on the balance of power between rival coalitions.

Whether this task force evolves into a stabilizing maritime institution or a precursor to hardened bloc competition will depend on its ability to balance deterrence with inclusivity.

By Tsega’ab Amare, Researcher, Horn Review