12

Mar

Ethiopia-Somalia Reconciliation and the Shifting Power Dynamics in the Horn of Africa

The geopolitical landscape of the Horn of Africa is undergoing a profound transformation, marked by the recent reconciliation between Ethiopia and Somalia. This diplomatic breakthrough, culminating in Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s visit to Mogadishu, signifies more than a bilateral rapprochement. It is a recalibration of regional alliances that challenges the strategic calculations of external actors, particularly Egypt and Eritrea, and signals a new phase in Ethiopia’s pursuit of economic and strategic autonomy.

For Ethiopia, the Red Sea remains at the core of its long-term vision. Historically connected to these vital maritime routes, its landlocked status has constrained both its economic potential and geopolitical influence. The country’s efforts to secure access to a port, despite resistance from regional players, reflect a broader strategy of reclaiming a lost advantage. The Memorandum of Understanding with Somaliland last year, though met with fierce opposition from Mogadishu, was a calculated move in this direction. Yet, the subsequent fallout with Somalia only reinforced the challenges Ethiopia faces in navigating the Horn’s complex web of alliances.

The diplomatic crisis that ensued from the Somaliland agreement provided an opening for Egypt and Eritrea to reinforce their efforts to counterbalance Ethiopia’s growing influence. Cairo, long at odds with Addis Ababa over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, sought to exploit the rift between Somalia and Ethiopia to weaken its regional adversary. Asmara, driven by deep-seated historical tensions and strategic anxieties, embraced the opportunity to align itself with Mogadishu in a broader effort to contain Ethiopia’s ambitions. The emergence of a tripartite understanding among Egypt, Eritrea, and Somalia signaled a concerted push to encircle Ethiopia diplomatically and strategically.

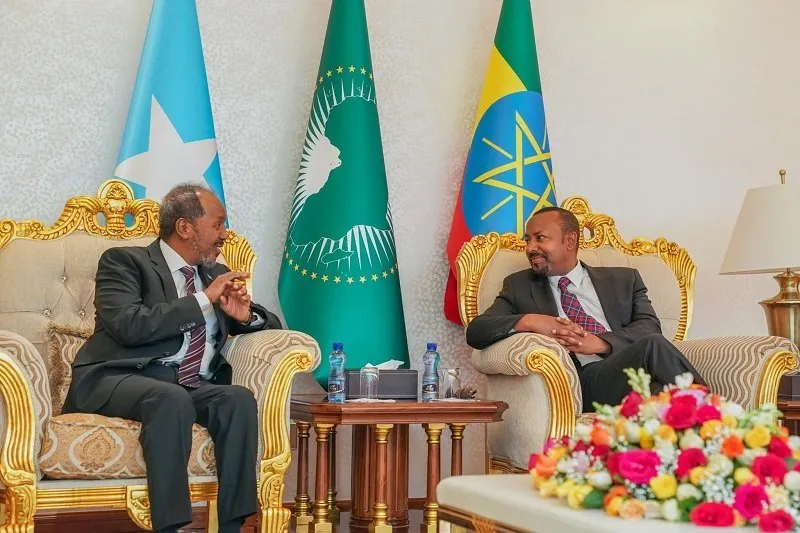

The intervention of Türkiye as a mediator shifted the trajectory of this escalating crisis. The Ankara Agreement, brokered under the stewardship of President Erdoğan, laid the groundwork for Ethiopia and Somalia to de-escalate tensions and explore avenues for cooperation. The gradual normalization of diplomatic ties, culminating in President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud’s visit to Addis Ababa and subsequent security agreements, restored a degree of stability to the region. Abiy Ahmed’s visit to Mogadishu, therefore, was not merely symbolic; it cemented a shift in regional alignments, positioning Ethiopia and Somalia as partners rather than adversaries.

This realignment carries profound implications for Egypt and Eritrea, both of whom had relied on Somalia as a counterweight to Ethiopia’s expanding influence. Egypt’s strategy, predicated on leveraging regional alliances to exert pressure on Ethiopia regarding the Nile, now faces significant setbacks. While Cairo may maintain military and political ties with Mogadishu, its ability to use Somalia as a strategic lever has diminished. The prospect of direct negotiations over GERD, an outcome Egypt has long sought to avoid, becomes increasingly likely in the absence of a robust regional coalition against Ethiopia.

For Eritrea, the consequences are even more acute. Asmara’s approach to regional politics has historically relied on fostering divisions and capitalizing on instability to maintain strategic leverage. The collapse of the tripartite understanding with Somalia and Egypt leaves Eritrea increasingly isolated. With Ethiopia and Somalia finding common ground on security and economic cooperation, the environment that once allowed Asmara to position itself as a key player in the region is rapidly eroding. Eritrea’s economy, heavily dependent on mining and remittances, lacks the diversification and scale to compete with Ethiopia’s expanding economic footprint. In an environment that is gradually tilting toward regional integration and cooperation, Eritrea’s entrenched posture of isolationism threatens to render it increasingly marginal.

Tensions between Ethiopia and Eritrea appear poised to escalate further. The mobilization of Eritrean military reserves and tightened travel restrictions indicate growing unease in Asmara. Accusations from Ethiopian political figures, including former President Mulatu Teshome, that Eritrea is fueling unrest in northern Ethiopia reflect a broader perception within Addis Ababa that Asmara remains a destabilizing force. While not an official government position, such statements underscore the fragility of the Ethiopia-Eritrea relationship and the potential for renewed hostilities.

Yet, amid these rising tensions, the Ethiopia-Somalia reconciliation offers a compelling lesson. The ability to transcend historical grievances and forge a path toward mutual interests is not merely an idealistic aspiration but a strategic necessity. Ethiopia and Somalia, once on the brink of outright hostility, have demonstrated that de-escalation and cooperation are viable alternatives to perpetual conflict. For Eritrea, the path forward remains a choice between continued isolation or recalibrating its approach to regional politics.

Ethiopia, despite its strategic gains, would also benefit from extending a diplomatic overture to Eritrea. Sustainable regional stability will not be achieved through geopolitical maneuvering alone; it requires an active commitment to dialogue and economic collaboration. The evolving dynamics in the Horn of Africa underscore a broader reality: enduring influence is not secured through isolation and confrontation but through consensus-building and regional integration. If the Ethiopia-Somalia reconciliation is any indication, the potential for a more stable and cooperative Horn of Africa is within reach, provided its leaders choose to embrace it.