11

Feb

Conflict-Enabled Hydro-Hegemony: Sudan’s Collapse and Egypt’s Nile Strategy

The war in Sudan, which began in April 2023, has fundamentally reconfigured the hydro-political and economic landscape of the Nile Basin and the wider Horn of Africa. For Egypt, the basin’s traditional hydro-hegemon, the disintegration of the Sudanese state presents a strategic paradox. The humanitarian fallout, marked by the displacement of more than 12 million people and the collapse of formal economic channels, constitutes a profound regional security crisis. Yet the conflict has also catalyzed several of Cairo’s long-standing developmental and strategic priorities by suspending the rise of a midstream partner that had begun to recalibrate basin politics.

This dynamic reflects what may be termed as conflict-enabled hydro-hegemony, a condition in which the collapse of a co-riparian state unintentionally consolidates the strategic position of an established downstream power. Sudan’s incapacitation has deferred competing patterns of water use, strengthened Egypt’s diplomatic narrative, and redirected segments of regional economic geography northward. These developments appear less the product of deliberate design than the structural consequence of state fragmentation in a transforming river system.

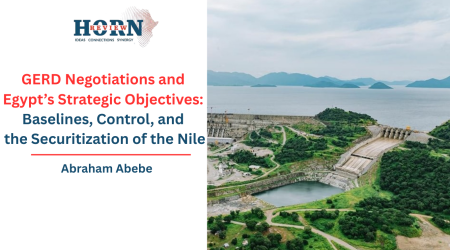

Any assessment of Egypt’s posture must begin with the historical architecture of Nile governance. The 1929 and 1959 Nile Waters Agreements institutionalized a downstream duopoly, allocating the river’s flow to Egypt and Sudan while marginalizing upstream states, despite Ethiopia being the primary contributor to the Blue Nile at roughly 85 percent of its volume. Over time, this framework produced what scholars describe as hydro-hegemony, a system where legal, material, and diplomatic power reinforce downstream control.

For decades, Sudan functioned as both partner and buffer within this order. Starting from the past decade, however, Khartoum’s outlook witnessed a gradual recalibration. Rather than viewing the Nile solely through the prism of Egyptian security, Sudan increasingly recognized the river as a vehicle for domestic modernization. This shift became most visible in its evolving stance toward the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.

Initial Sudanese skepticism, rooted in dam safety concerns and quota sensitivities, gradually gave way to a cautious pragmatism as the developmental logic of the GERD became harder to ignore. The prospect of regulated flows offered a transformative shift from erratic seasonal flooding to stable, year-round irrigation, while sediment control promised to extend the lifespan of Sudan’s own downstream reservoirs. By 2014, Sudan had effectively declared neutrality in the dispute, and despite intermittent friction over Ethiopia’s unilateral filling schedules in the early 2020s, Khartoum remained functionally aligned with Addis Ababa on the technical merits of the project. Ultimately, the dam represented more than just affordable hydropower; it offered the hydraulic stability required to modernize and expand Sudan’s vast agricultural schemes.

The civil war, however, has abruptly terminated this Sudanese pivot. Institutional collapse, infrastructural destruction, and administrative fragmentation have transformed Sudan from a prospective agricultural and energy partner into a vulnerable downstream actor once again reliant on Egyptian security backing. A coordinated midstream state that is capable of independently leveraging the GERD would have complicated Cairo’s diplomatic posture. A fractured Sudan in the contrary, reinforces Egypt’s preference for a somewhat familiar downstream alignment.

Importantly, this outcome does not require attribution of intent. Rather, Sudan’s incapacitation has produced conditions that align with Egypt’s traditional emphasis on basin stability over renegotiation. In this sense, the war illustrates how conflict-enabled hydro-hegemony can emerge through structural disruption rather than strategy.

The most consequential advantage for Egypt lies in the paralysis of Sudan’s agricultural future. Different analysts long argued that the GERD would provide the regulated flow necessary to irrigate a new 500,000 of hectares across Sudan, potentially elevating the country into a regional breadbasket without requiring Additional costs. Such a trajectory carried implications for downstream consumption patterns. A Sudan capable of fully utilizing its 18.5 billion cubic meter allocation, and potentially seeking revisions, would have narrowed the surplus flows upon which Egypt has historically depended.

The war has effectively deferred this possibility. The Gezira Scheme, long the backbone of Sudan’s agrarian economy, has suffered severe disruption as canals deteriorate, administrative leadership fragments, and financing mechanisms evaporate. Technical debates about cropping intensity have been overtaken by the more immediate reality of systemic collapse. The hydrological implication is straightforward: water that might have supported midstream agricultural expansion continues downstream toward Lake Nasser. While Egypt might not have engineered this outcome, it reinforces Cairo’s longstanding assumption that unused upstream or midstream capacity stabilizes downstream supply. For now, the distributional pattern remains rooted less in contemporary negotiation than in historical precedent.

The economic consequences further illustrate the mechanics of conflict-enabled hydro-hegemony. Sudan historically supplied Egypt with affordable red meat, and although the conflict initially disrupted this trade, deteriorating formal systems soon generated parallel markets. War redistributes value chains across borders. Sudanese pastoralists, confronting insecurity and rising transaction costs, increasingly resorted to distressed sales, while the destruction of domestic slaughterhouses pushed the export of live animals rather than processed meat. Value-added activities, from fattening to leather production, have consequently migrated northward, allowing Egyptian facilities to capture stages once embedded within Sudan’s economy.

Gold reflects an even more strategic shift. As state authority weakened, mining decentralized, artisanal production expanded, and smuggling routes intensified, many converged toward Egypt. The displacement of Sudanese engineers, geologists, and miners has produced an inside-out transfer of human capital tied to the Nubian Shield, enhancing Egypt’s capacity to accelerate its own extraction ambitions. Simultaneously, the erosion of Sudan’s refining infrastructure positions Egypt as a processing and logistical hub, advancing Cairo’s aspiration to sit at the center of regional mineral flows. Instability, in effect, removes a potential competitor while reorganizing economic geography in Egypt’s favor.

Egypt’s Nile strategy has often favored incremental arrangements over basin-wide legal transformation. Large multilateral frameworks risk diluting historical rights, whereas fragmented orders preserve maneuverability. A stable Sudan might have revisited its treaty posture or engaged more actively with cooperative basin initiatives. A Sudan preoccupied with existential survival is unlikely to alienate a critical diplomatic partner.

This is not fragmentation as deliberate policy but fragmentation as a structural consequence. By embedding water politics within a broader security architecture through defense coordination and regional partnerships, Cairo reinforces its role as an indispensable security actor rather than merely a downstream claimant. Here again, conflict-enabled hydro-hegemony operates less through coercion than through asymmetries of institutional resilience.

Yet structural comfort can conceal strategic hazards. Demographic expansion, electrification demands, and climate volatility are steadily pushing upstream states toward storage-based development. In this context, the GERD appears less an anomaly than an expression of continental momentum toward energy sovereignty. The deeper question may no longer be whether the basin will change, but how equitably that change will be negotiated.

Short-term strategic relief derived from Sudan’s incapacitation could obscure a longer-term compression of Egypt’s adaptive space. River basins shaped by technological transformation rarely revert to inherited equilibria. Durability tends to favor states that adjust early to emerging hydrological realities rather than those that rely on familiar orders.

What emerges, therefore, is a paradox of destabilizing gains. The war in Sudan is first and foremost a human catastrophe, yet within the logic of realpolitik, it also functions as a strategic reset that temporarily reinforces Egypt’s hydro political instincts. By disabling the administrative and physical capacity of a potential midstream balancer, the conflict preserves downstream flow patterns, strengthens Cairo’s diplomatic narrative, and channels resource networks toward Egyptian markets.

A basin governed by fractured states may offer immediate predictability, but it cannot indefinitely resist structural transformation. Egypt’s flawed inherited doctrine, shaped by history, geography, and institutional memory, has proven resilient. Whether it proves equally adaptable remains the more consequential question.

In the Nile Basin, power is no longer determined solely by treaties or topography. It increasingly rests on which states remain functional as others fracture, and on which among them recognize that the future of shared rivers will be secured less through control than through negotiated adaptation.

By Tsega’ab Amare, Researcher, Horn Review