11

Dec

The Heglig Checkmate: How the Fall of Sudan’s Oil Hub Redefines the War

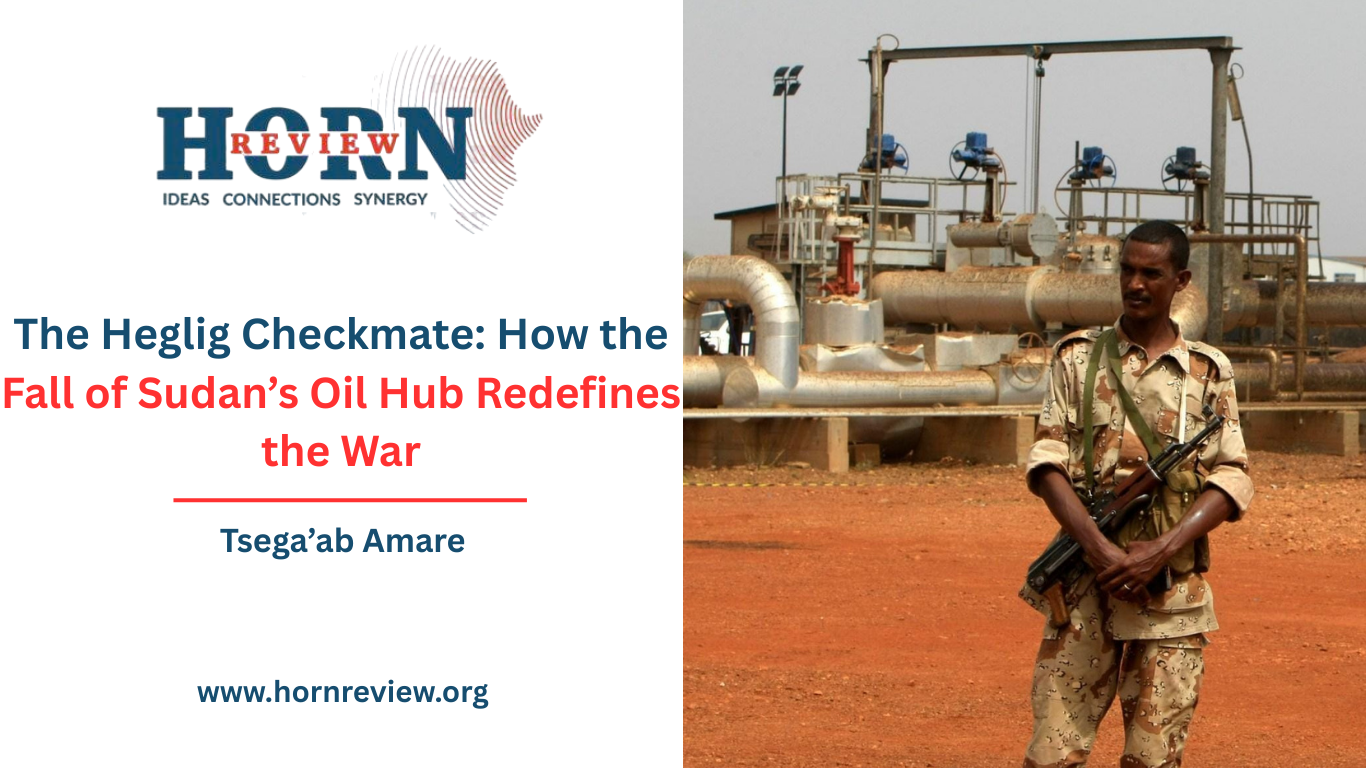

The seizure of Heglig by the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) on December 8, 2025, constitutes a fundamental shift in the Sudanese civil war, moving the conflict from a territorial struggle for the capital to a direct contest for economic sovereignty.

The strategic, oil-rich locale, which had long served as the functional border between North and South Sudan, now places the RSF in a position of unprecedented leverage. The paramilitary group has effectively transformed into a resource-controlling entity with direct influence over two sovereign states.

The Prelude: The Fall of Babanusa

The fall of Babanusa last week was the decisive precursor to the current crisis. For nearly two years, the SAF’s 22nd Infantry Division in Babanusa had withstood a grueling siege, acting as the primary bulwark preventing the RSF from linking their strongholds in Darfur with the oil basins of the south.

When the 22nd Division headquarters was finally overrun on December 1, the SAF lost its operational spine in the region. The defeat forced a disorganized retreat and removed the only significant military obstacle between the RSF lines and the oil fields.

The Checkmate: The Seizure of Heglig

The seizure of Heglig was rapid and absolute. Reports confirm that the SAF’s 90th Infantry Brigade, tasked with defending the oil infrastructure, withdrew after brief resistance. Hundreds of soldiers have reportedly fled across the border into South Sudan’s Unity State.

By capturing Heglig, the RSF has achieved three military objectives:

- Territorial Contiguity: They have consolidated West Kordofan, creating a contiguous zone of control stretching from West Darfur to the border of South Sudan.

- Denial of Resources: They have stripped the SAF of its last remaining foothold in the Muglad Basin oil fields.

- Border Control: They now dictate the flow of personnel and goods along a vital stretch of the Sudan–South Sudan border.

The significance of Heglig cannot be overstated; it is essentially the “nervous system” of the region’s oil economy. While the oil wells are valuable, the Central Processing Facility (CPF) at Heglig is irreplaceable.

While the RSF portrays the capture of Heglig as an absolute military victory and the collapse of the SAF’s 22nd Infantry Division, the SAF has strategically countered with the narrative of a deliberate and pre-emptive tactical withdrawal. This claim, although difficult to verify amidst the chaos, asserts that the SAF prioritized the preservation of the highly sensitive CPF. In what is deemed asa move ostensibly designed to prevent the catastrophic, long-term infrastructure damage that would result from urban combat within the facility.

Regardless of intent, the consequence, however, is the same: the SAF has lost its last significant military foothold in West Kordofan, granting the RSF contiguous control of a vast, resource-rich swathe of territory stretching from Darfur to the South Sudan border.

The most immediate complication to the RSF’s perceived checkmate is the sudden emergence of South Sudan as a potential military actor. Lt. Gen. Johnson Olony, South Sudan’s Deputy Chief of Defense Forces for Mobilization and Disarmament, told reporters that they are considering an intervention to secure Heglig for the purpose of “regional stability.”

This move is motivated by an existential economic threat; with over 90% of Juba’s revenue reliant on the Heglig CPF, any disruption is unacceptable. The SSPDF is simultaneously receiving and disarming fleeing SAF soldiers, an act that neutralizes Khartoum’s manpower while creating a possible buffer force. The potential SSPDF deployment, whether a negotiated military presence or an outright seizure, would deny the RSF the finality of their victory, compelling General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo to negotiate with Juba.

For the SAF-led government in Port Sudan, the loss is twofold: They lose the transit fees paid by Juba, which were a critical source of hard currency for the war effort. And the loss of domestic production from the Heglig and Bamboo fields will exacerbate existing fuel shortages, crippling SAF logistics and further alienating the civilian population in army-held areas.

The seizure of Heglig, therefore, forces a recalibration of political legitimacy in the region. President Salva Kiir’s government in Juba is now in an impossible position. Historically, Juba has maintained relations with the SAF-led Sovereign Council as the recognized government. However, pragmatism may now force Juba to negotiate directly with General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo to keep the oil flowing.

- Scenario A: Juba negotiates with the RSF, effectively granting the paramilitary group de facto state recognition. This would deeply fracture relations with the SAF.

- Scenario B: Juba refuses to engage, risking an immediate economic collapse that could trigger civil unrest or a coup within South Sudan due to unpaid salaries for its own military.

Sudan’s protracted conflict has forced global stakeholders to directly confront the reality of Sudan’s fragmentation. The loss of Heglig follows the earlier disruption of China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC)-operated Block 6 further west, an area now also under RSF control. CNPC’s recent request for an early termination of its decades-long contracts underscores the company’s despair over the security situation and the financial unsustainability of operations. This signals a potential major exit of Sudan’s primary strategic partner; demanding Beijing pivot its diplomatic efforts toward Hemedti to protect its remaining interests.

Concurrently, the proxy dimensions of the conflict, highlighted by alleged support for the RSF from the UAE and military assistance for the SAF from Iran, will intensify. The RSF’s new economic leverage strengthens the hand of its external backers, raising the cost for the SAF government and its allies to negotiate a settlement, while severely constraining the delivery of humanitarian aid to millions displaced in the newly contested Kordofan region.

The fall of Heglig marks more than a military defeat; it signifies the accelerating fragmentation of Sudan and the dawn of a new, resource-driven phase of conflict. The RSF’s transformation into a resource-controlling quasi-state forces all regional actors, especially Juba, to make pragmatic, painful choices that will reshape alliances and sovereignties.

As external powers recalculate their stakes in a divided nation, the war’s center of gravity has decisively shifted from the political fate of Khartoum to the economic survival of the entire region, locking Sudan into a protracted struggle where control of oil fields outweighs control of the capital.

By Tsega’ab Amare, Researcher, Horn Review