5

Oct

Ethiopia, Eritrea And The Flawed Reading Of The Port Question

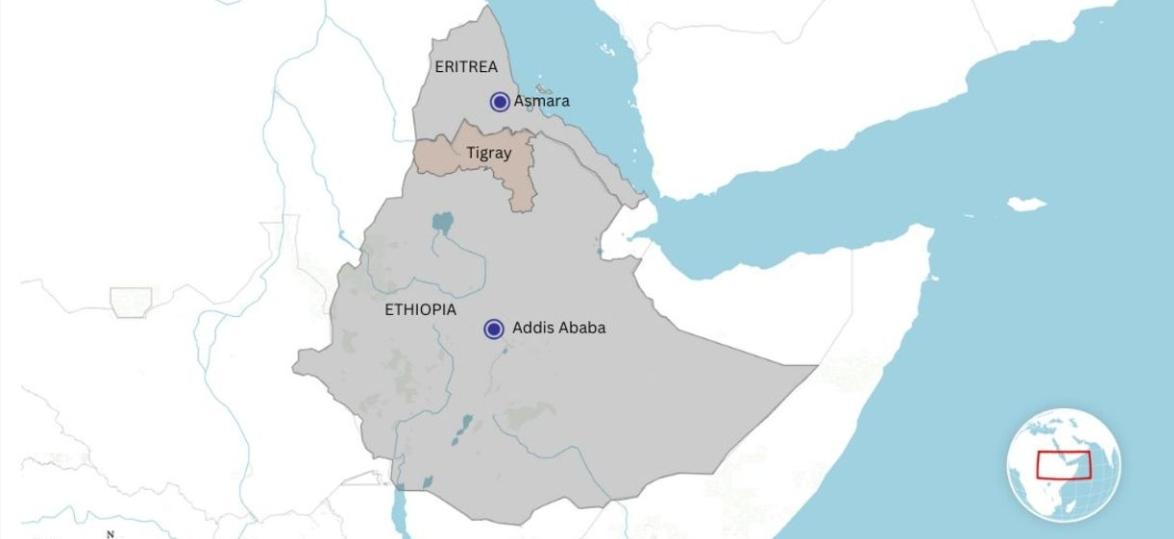

Recent commentary by the Economist has painted an alarming picture of Ethiopia and Eritrea standing on the edge of war, with Addis Ababa supposedly preparing to march north to claim a Red Sea port. The claim rests on the idea that Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has openly declared intentions over Assab, echoed by Ethiopia’s National Defence Forces. The picture is then expanded with speculation of Egyptian and Sudanese involvement, along with a scenario of Tigrayan secession, in which the collapse of Isaias Afwerki’s regime could spark a “Greater Tigray” joined to its Eritrean cousins. The narrative is perhaps intentionally dramatic, yet it is deeply misguided.

Much like the conflict in Tigray, outside readings of Ethiopia–Eritrea relations often miss the realities on the ground. The assumptions behind this scenario rest on familiar tropes. They suggest that Ethiopia’s sea-access question is tied exclusively to Eritrea, that Addis Ababa has no option other than force, and that Tigrayans are waiting for an opportunity to secede. These ideas confuse Ethiopia’s national questions with the propaganda of its rivals.

Take Assab as an example. In Ethiopia, the story surrounding Assab is rooted in regret rather than conquest. The loss of access to the sea is remembered as a historical mistake, the outcome of Eritrea’s secession and the decision of the TPLF-led government at the time to accept landlocked status with little consideration for Ethiopia’s long-term interests. Many in the current generation of Ethiopian leaders, including the prime minister, have described this as a strategic blunder. That frustration, however, does not translate into a plan for war.

The history of Ethiopia’s access to the Red Sea is long and complex. For centuries, Ethiopia has confronted foreign incursions, colonial ambitions, and shifting borders. The coastline has always been regarded as a matter of national interest, defended at different times through diplomacy and through force. It has never been reduced to a simple binary of Ethiopia against Eritrea. To suggest today that Ethiopia’s port question revolves solely around Eritrea is to overlook this broader context.

Even so, Ethiopian officials occasionally speak of Assab with sentiment. Some military leaders recall its history of exclusive Ethiopian use. Yet sentiment is distinct from policy. Addis Ababa has already shown through recent moves, most clearly its agreement with Somaliland, that the pursuit of sea access is being approached through diverse and pragmatic channels. It is not fixed upon Assab. Reducing the matter to a single port and predicting inevitable war with Eritrea is to fall into the same alarmism that President Isaias has promoted for decades.

Asmara’s government has long thrived on the narrative of imminent threat. For three decades, Eritrea’s ruling party has justified its repressive system by pointing to Ethiopia as a looming aggressor. Each time public discussion in Ethiopia touches the question of sea access, Asmara responds with alliances and posturing. When Ethiopia signed its memorandum of understanding with Somaliland, Eritrea hurried to form an anti-Ethiopian alignment with Egypt and Somalia. The method is a classic one. Cast Ethiopia as the aggressor, rally allies, and keep Eritreans fearful of invasion. In this sense, today’s talk of war is more a reflection of Eritrean insecurity than Ethiopian intention.

To understand how this situation emerged, it is necessary to look back to 2018. When Abiy Ahmed became prime minister, he introduced ambitious plans to reset relations in the Horn. His outreach to Eritrea aimed at peace and reconciliation rather than confrontation. The world watched as Abiy and Isaias embraced, raising hopes for a new chapter. Those hopes quickly faded, undone by two spoilers: the TPLF and the PFDJ.

The TPLF, displaced from its dominant role in Addis Ababa, lashed out. Its surprise attack on the Northern Command triggered a devastating conflict that drew in Eritrea as well. Amid the chaos, Asmara seized the opportunity to settle scores with its bitter enemy. When the conflict ended, however, Eritrea remained unsatisfied. The PFDJ, consistent with its long-standing posture, retreated once again into suspicion and hostility. The brief window for genuine peace closed.

This brings us back to the present. The renewed talk of war has little to do with Assab itself and much more to do with political calculations in Mekelle and Asmara. The TPLF, weakened by conflict and facing growing unpopularity within Tigray, requires a new narrative to mobilize its constituency. “Greater Tigray” offers such a rallying cry, promising unity with Eritrean cousins and a break from Ethiopia. The PFDJ, meanwhile, sees Ethiopia’s stability as the greatest danger to its rule. An Ethiopia at peace and at ease with itself would strip away Asmara’s justification for its alarmist posture.

Here the paranoia of Eritrea and the opportunism of the TPLF intersect. Both gain from stoking fears of Ethiopian aggression, and both gain from the idea of a looming conflict. To accept these claims at face value is to confuse political theatre with actual reality. The real danger is not an Ethiopian plan to invade Eritrea, but the persistence of actors who cannot coexist with peace. The TPLF still struggles with its reduced role in Ethiopian politics. The PFDJ still clings to its siege mentality. Together they create narratives, noise, and flashpoints. Yet these remain distinct from Ethiopia’s national policy. Ethiopia’s question of sea access is indeed central to its future. It is a matter of economics, security, and identity. To leap from this fact to predictions of war with Eritrea is to adopt a flawed interpretation. The issue is older, broader, and more complex than Asmara’s fears allow.

The narrative of imminent danger has a familiar resonance. In 2020, it was central to the TPLF’s decision to escalate into conflict. Today, the same framing of Ethiopian aggression is used to explain the increasingly hostile posture of both the TPLF and the PFDJ. For each, it offers a way to justify their standing and to press for a more favourable political outcome. Ethiopia’s position, however, remains distinct. The agitation surrounding talk of war reflects more the insecurities of Asmara and the calculations in Mekelle than it does the reality of the thinking in Addis Ababa.

By Mahder Nesibu, Researcher, Horn Review

This article is a review of the Economist’s publication titled “Africa’s most secretive dictatorship faces an existential crisis” – https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2025/10/02/africas-most-secretive-dictatorship-faces-an-existential-crisis