14

Aug

Berbera and Beyond: Ethiopia in the Israel–Somaliland Nexus

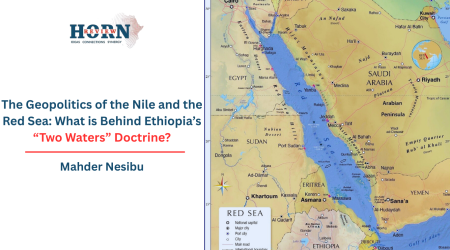

In a region where many actors are in play, reported diplomatic interest and talks between Israel and Somaliland will unfold a multi-dynamics situation (Rende, 2024). While framed as bilateral engagement, this development strikes at the heart of Ethiopia’s most vital national interests in security, economic survival, and regional influence. Understanding this isn’t about distant geopolitics, it’s about Ethiopia’s path to stability and prosperity in a rapidly shifting landscape. The Houthi missiles attack in the Red Sea shipping, Egypt’s persistent maneuvers, and Ethiopia’s own legitimate quest for sea access aren’t isolated events. They form a complex, dangerous, yet potentially transformative puzzle where the Israel-Somaliland gambit could be a crucial piece for the region.

For a landlocked Ethiopia, every port arrangement is less a matter of preference than a matter of national survival. The reported quiet conversations about Israel edging toward a deal with Somaliland are therefore not distant noise, they are potential tectonic shifts (Rende, 2024). If handled rightly, Berbera could become more than an alternative to Djibouti as evidenced in the MoU between Ethiopia and Somaliland. It could be the corridor that breaks a structural chokepoint in Ethiopia’s economy. But if handled poorly, it will become another arena where external powers shape Ethiopia’s options without Addis at the table.

Alternative routes through Sudan or Kenya are distant, underdeveloped, or unstable except Port of Assab. The January Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Somaliland was a strategic move to escape a strategic suffocation. This promised potential recognition of Somaliland in exchange for leased military and commercial access to the port of Berbera. At the time, a viable, shorter, potentially cheaper corridor to the sea seemed within reach.

When it comes to Israel, its interest in Somaliland is sensible when read through basic strategic arithmetic. The collapse of safe passage through the southern Red Sea and Bab el-Mandeb since late 2023 has raised insurance premiums and pushed carriers to take the long way around Africa (Saul & Reid, 2025). For Israel, which depends on prompt maritime links to Asia and Europe through its port of Eilat, ports on the Gulf of Aden offer redundancy and security of supply. Somaliland’s Berbera sits at a natural transshipment node, accessibility and under a regional authority willing to court outside partners. The logic is when a major sea lane becomes fragile, nearby high-quality ports acquire outsized strategic value, especially its engagement with Somalia. In addition, Israel might seek to counter Turkey’s influence in the region, mirroring the rivalry between the two countries in Syria, where each tries to increase its leverage and blunt the other’s gains (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2025).

Furthermore, Berbera is not an abstract possibility. DP World’s involvement has already translated into tangible infrastructure and commercial frameworks. The port’s phased expansion, a free-zone plan, and existing agreements across Hargeisa, DP World and Addis create a foundation on which faster economic integration can be built. That said, the planned corridor is a developing physical asset that, if scaled and properly connected to Ethiopia’s eastern hinterland, can competitively challenge Djibouti’s near-monopoly (DP World, 2021).

Into that commercial dynamic steps geopolitics. Israel’s courting of Somaliland is a strategic hedge more than commercial pragmatism. A presence on the Gulf of Aden gives Israel eyes on Yemeni Houthis, the Bab el-Mandeb chokepoint, and a degree of influence over maritime routes that have suddenly become vulnerable (Jerusalem Post 2024). Reports that Washington may be moving toward recognition of Somaliland only accelerate the momentum. American diplomatic cover would make follow-on partnerships easier for others. For Ethiopia as its ally, Israel’s arrival could be a force multiplier with Israeli security expertise and surveillance capabilities hardening the Berbera corridor against sea-borne and littoral threats (Yarom, 2025).

The UAE already sits at the center of this emergent architecture. DP World’s concession, Abu Dhabi’s regional posture, and the logic of the Abraham Accords combine capital, operational capacity, and political will ((Yarom, 2025). In practice this creates a potent coalition with Emirati investment and operating the port, Israeli know-how improving security and surveillance, and Ethiopian trade providing the throughput that makes the whole project commercially viable. That mix turns Berbera from a regional upgrade into a strategic Red Sea asset. For Addis Ababa, aligning its economic and diplomatic weight with these partners could convert a port into a durable lifeline.

However, strategic opportunity invites strategic resistance. Cairo views any enhancement of Ethiopian access to the Red Sea, especially via a port outside traditional Egyptian influence (like Djibouti), with profound suspicion. An Ethiopia-Somaliland-Israel alignment would be seen in Cairo as a double threat. A calibrated Egyptian response was to be expected, and it is already underway. Cairo will likely double down on supporting Somalia’s central government in Mogadishu, hoping to scuttle any deal with Somaliland and keep Ethiopia contained. Expect increased Egyptian diplomatic pressure, potential covert support for anti-Somaliland elements like the SSC-Khatumo militias in eastern Somaliland, and efforts to rally the Arab League against any recognition moves. Ethiopia must therefore treat stabilization of Somaliland as a strategic imperative as much as a commercial one.

Ethiopia’s MoU hinted at possible future recognition of Somaliland. Israel engaging adds immense weight to Somaliland’s quest for legitimacy. While full UN recognition remains distant, this functional engagement of trade, security cooperation, diplomatic talks chips away at the taboo.

That brings back to practical policy Ethiopia should pursue, which are security and balance. Security integration is the major pillar. A loose, informal understanding will not survive the pressures of maritime conflict, transnational crime, or proxy competition. Ethiopia should institutionalize intelligence sharing with Israel, UAE and Somaliland, coordinate maritime patrols, and explore technologies that shore up port resilience, including surveillance and counter-missile measures where appropriate. Israeli experience in port security is relevant, so too is the need to ensure any foreign security presence serves Ethiopian sovereignty rather than undermining it.

Diplomatic balance is the other requirement. Addis cannot burn bridges across the Arab world or alienate institutions like the African Union. Raising the MoU again with Somaliland, as Berbera must be presented as an economic necessity, a pragmatic route that complements, not supplants, Somali sovereignty claims or the integrity of existing regional arrangements with the support of the Emirates. At the same time, Ethiopia should sustain discreet channels with Hargeisa, support its governance and capacity efforts, and work with partners to defuse potential flashpoints in contested areas such as the SSC-Khatumo region.

Finally, plan for sabotage and second-order effects. Expect targeted efforts to destabilize the corridor, whether through political maneuvers, proxy support to local militias, or information campaigns. Ethiopia’s response must be layered in protective investments in governance and services that reduce local grievances, contingency security arrangements that limit disruption, and a diplomatic campaign that isolates actors who would benefit from instability.

The Red Sea has become more than a shipping lane. It is an arena where transport economics, maritime security, and great-power competition intersect and where Ethiopia’s future prosperity will be materially shaped. Berbera offers a practical escape from over-reliance on Djibouti and a geopolitical lever against adversaries who would fence in Ethiopian development.

By Yonas Yizezew, Researcher, Horn Review

REFERENCES

Rende, A. V. (2024). Israel’s quest for strategic depth in the Horn of Africa through Somaliland. Middle East Monitor

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. (2025). The Middle East’s other escalating rivalry. Emissary.

Saul, J., & Reid, H. (2025). Red Sea trade route will remain too risky even after Gaza ceasefire deal, industry executives say. Reuters.

DP World. (2021). Ministry of Transport of Ethiopia and DP World sign MoU for the development of the Ethiopian side of the Berbera Corridor [Press release]. DP World.

Jerusalem Post Staff. (2024). Israel eyes Somaliland base bid to counter threats from Yemen’s Houthis, bolster security – report. The Jerusalem Post.

Yarom, A. (2025). Gateways to the Red Sea: The case for Israel–Somaliland normalization. Atlantic Council.