17

Jul

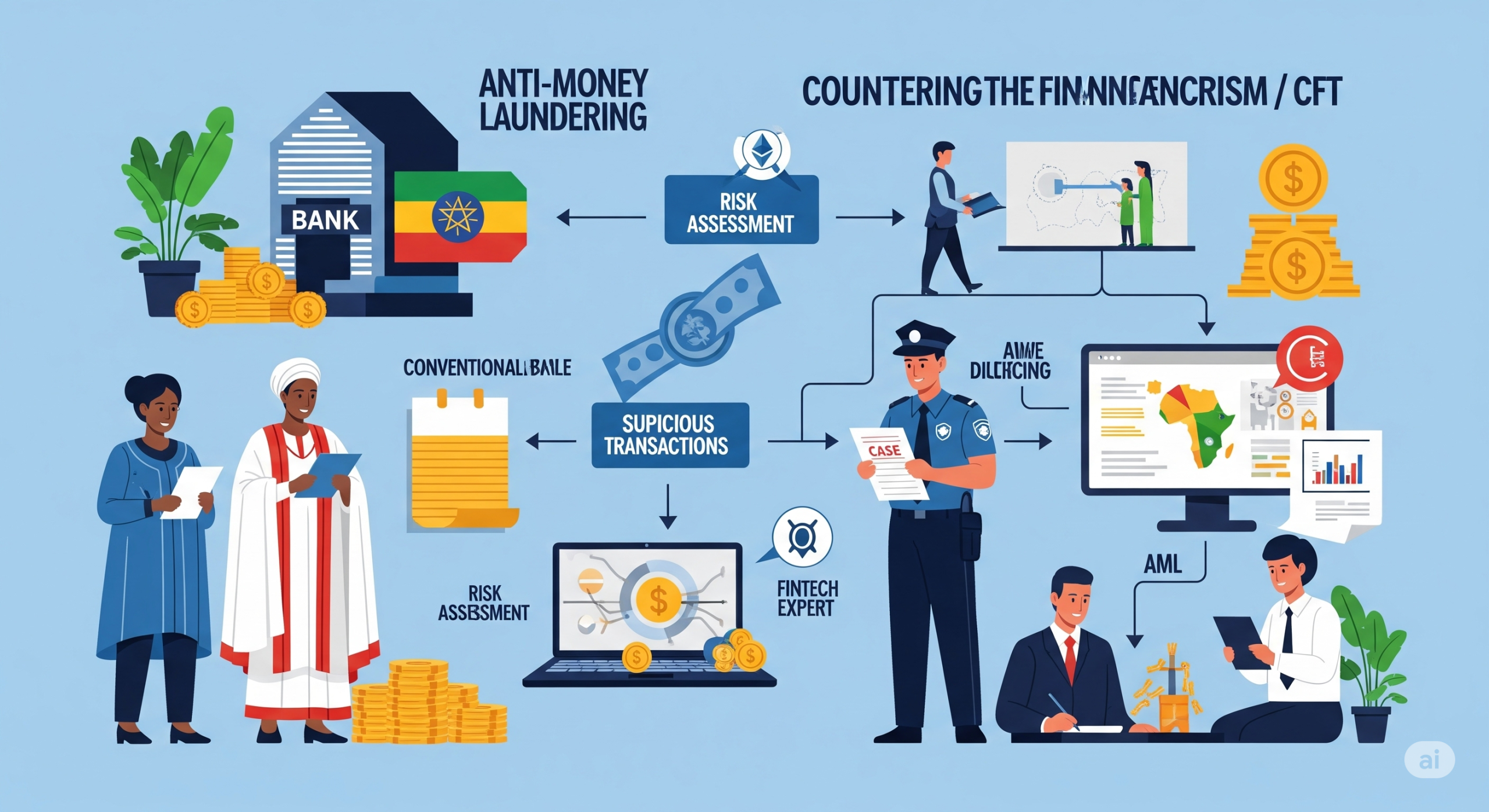

Getting Risk Right: From Compliance to Context in AML/CFT

Lessons from Ethiopia’s FATF ICRG Process, National Risk Assessment, and CFT Reforms

By Nolawi M. Engdayehu

What does it take to move from FATF compliance to real institutional resilience? Drawing from Ethiopia’s second National Risk Assessment and sectoral reviews I led, this piece outlines how low-capacity and transitional states can build credible, context-driven AML/CFT systems. The lessons are not only technical—they are political, strategic, and tied to governance reform.

Introduction

Standard approaches to Anti-Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) often prioritize formal compliance over functional effectiveness. Yet in states facing institutional fragmentation, limited capacity, or post-conflict recovery, such models can fall short—risking implementation gaps and reform fatigue.

This article draws on Ethiopia’s recent efforts—especially its second National Risk Assessment (NRA) and sectoral assessments, to show how context-aware, adaptive approaches can better align AML/CFT frameworks with governance realities. By moving beyond compliance toward systems that learn, iterate, and respond to local dynamics, reforming jurisdictions can build more resilient and effective AML/CFT regimes. The insights presented aim to guide policymakers in international organizations and technical partners toward practical and tailored risk management solutions.

1. From Template to Context: Reframing Risk

Standardized FATF methodologies provide consistency and benchmarking, but they may not fully capture systemic vulnerabilities in fragile or rapidly changing contexts. Economies dominated by informal transactions, remittance corridors, and hawala networks, traditional indicators—such as suspicious transaction reports or bank-based cash thresholds—often underrepresent actual risk exposure and critical vulnerabilities are missed by standard tools. Here, context itself is part of the data.

Effective AML/CFT strategies in these environments require grounding in political economy realities. Risk assessments should ask: Which sectors benefit from opacity? How are informal systems used for both licit and illicit activities? Where do institutional and regulatory asymmetries allow risks to proliferate? Ethiopia’s experience demonstrates that risk must be viewed not as a static formula but as a function of capacity, institutional mandates, and real-time exposure.

2. Understanding Risk as a Function of Capacity and Exposure: A Shift in Focus

AML/CFT risk is commonly defined as threats multiplied by vulnerabilities and consequences. Yet, capacity and context shape how these manifest. In low-capacity settings, risk often remains invisible—not because it is low, but because it is undetected.

Ethiopia’s second National Risk Assessment (NRA) applied this insight to Designated Non-Financial Businesses and Professions (DNFBPs), revealing significant variation across subsectors. Real estate, car dealerships, and dealers in precious metals and stones rated Medium-High to High, while lawyers and notaries ranked lower. Overall, DNFBPs were assessed as Medium-High risk.

However, the elevated risk wasn’t solely due to exposure. Institutional fragmentation, unclear supervisory mandates, and weak compliance enforcement played significant roles. For example, some sectors had no formal licensing or reporting obligations, leading to complete supervision blind spots. Identifying these structural issues enabled Ethiopia to move from risk scoring to focused action—clarifying supervisory roles, prioritizing high-risk sectors, and rolling out targeted oversight.

This reframing—treating risk as both exposure and the capacity to mitigate—marks a shift from compliance to strategy, allowing countries to build resilience alongside reform.

3. Turning FATF Compliance into a Governance Tool

National Risk Assessments (NRAs) are often treated as compliance checkboxes to meet FATF timelines. Yet, when embedded into national systems, they can serve as powerful governance tools. Ethiopia’s second NRA demonstrates how a domestically led, institutionally embedded process can move beyond reporting to drive operational reform.

Rather than a one-off exercise, the NRA became a platform for regular data exchange, coordination, and policy alignment—linking the Financial Intelligence Service (FIS), supervisors, law enforcement, and financial institutions. This collaborative model improved the feedback loop and quality of risk data, identified typologies, and supported shared oversight. It also led to a nationally endorsed action plan with clearly assigned responsibilities and implementation timelines.

By institutionalizing the NRA process within government systems—and linking risk findings to supervisory decisions—Ethiopia showed how FATF-driven processes can evolve into inter-agency coordination mechanisms that enhance identification, detection, tracking, prevention, and response to financial crimes.

4. Beneficial Ownership and IFFs: Operationalization

Addressing illicit financial flows (IFFs) and achieving beneficial ownership (BO) transparency requires more than legal registries. Without quality data, institutional interoperability, and enforcement authority, BO systems risk becoming symbolic. Political economy factors—like trade mispricing and tax avoidance—underscore the need for real-time data-sharing, legal mandates, and sustained political will.

In Ethiopia, gaps in verifying BO information limited the ability of regulators and law enforcement to disrupt financial crime involving legal persons. Bridging these gaps required embedding BO transparency into the revised Commercial Code, launching a national ID system, and aligning policies across tax, corporate, and AML frameworks.

Yet legal reform alone is insufficient. Operationalization depends on effective institutional coordination. Countries must invest in the operationalization of BO systems—data verification protocols, real-time access for FIUs, and integration with tax and procurement systems. Ethiopia’s progress is promising, but sustained implementation will determine long-term impact.

5. Sectoral Reviews: DNFBPs, Virtual Assets, and Informality

Traditional AML/CFT assessments often under-engage Designated Non-Financial Businesses and Professions (DNFBPs) and informal financial systems. Ethiopia’s decision to expand sectoral reviews to include Virtual Assets (VAs) and Virtual Asset Service Providers (VASPs) reflects a shift toward more comprehensive risk mapping.

Globally, regulators still grapple with the complexity of VAs—marked by anonymity, borderless transactions, and weak legal consensus. These factors create vulnerabilities to terrorist financing, cybercrime, and illicit flows. Fragmented frameworks also generate enforcement blind spots and hinder institutional compliance assessments.

Ethiopia initially banned VAs and VASPs, but ongoing sectoral reviews allow regulators to monitor international developments and consider future supervisory models. Meanwhile, the NRA underscored the need for enhanced risk-based supervision of DNFBPs—anchored in practical tools, sustained engagement, and proactive incentives to foster a culture of compliance.

6. Countering Terrorist Financing: Building Enforcement Muscles

Ethiopia’s new AML/CFT investigative law marked a significant shift toward enforcement readiness especially for countering terrorism financing (CFT). The law enhanced prosecutorial powers to act on financial intelligence reports before incidents occur, enabled asset freezing mechanisms aligned with UNSCR 1373, and improved cross-agency coordination.

The establishment of joint Investigation Teams also facilitates parallel financial investigations of high-risk offenses and improves the traceability of cross-border illicit flows. Ethiopia’s CFT reform particularly prioritized high-risk sectors such as hawala operators, remittance agents, and NGOs operating in conflict-affected regions.

This approach—embedding CFT risk into the broader NRA and inter-agency response, avoids siloed approaches and constitutes a key part of a country’s integrated financial crime architecture. More consequentially, it also offers a replicable model for other ICRG jurisdictions facing similar risk environments.

7. Sequenced, Country-Led Reform with Peer-Informed Learning

Ethiopia’s AML/CFT reform has followed a phased and institutionally anchored process, emphasizing national ownership and informed adaptation. Early steps included expanding the legal mandate of the Financial Intelligence Service (FIS), reactivating a multi-agency National AML/CFT Committee, and joining the Egmont Group—measures that enabled stronger cross-border cooperation and improved coordination across finance, security, and justice sectors.

The NRA process, supported technically by the World Bank, guided the structured inclusion of high-risk DNFBPs into the supervisory framework and informed targeted legislation to address emerging risks such as virtual assets. This approach linked risk assessment to legal reform, supervision, and enforcement through a deliberate sequencing—from risk diagnosis to implementation.

Such models of reform should be increasingly supported. They underscore the importance of approaches that are not only externally compliant but also operationally embedded, institutionally coherent, and responsive to local conditions.

8. from ICRG Compliance to Reform

Countries under FATF’s ICRG review often face the challenge of meeting urgent compliance benchmarks while laying the foundation for durable, long-term system development. To consolidate progress and prepare for future mutual evaluations, Ethiopia now requires targeted, sequenced technical assistance that deepens operational capacity while supporting institutional alignment. Donors and international partners can play a catalytic role through the following priorities:

• Awareness and Ownership: Enhance whole-of-government understanding of FATF Recommendations, particularly how they apply to sectoral agencies and non-financial actors.

• Capacity Building: Develop technical skills on customer due diligence, STR filing, BO transparency, and sector-specific risk mitigation.

• Legal Harmonization: Support drafting of secondary legislation, inter-agency data-sharing agreements, and harmonized regulatory mandates.

• Applied Learning: Utilize typology-based training, scenario exercises, and localized case studies.

• Evaluation Readiness: Build real-time monitoring tools (preferably locally designed), feedback loops, and peer learning platforms.

9. Summary of Replicable Lessons

A summary of Ethiopia’s key AML/CFT lessons for peer countries:

1. Define Risk Contextually: Factor in informal economies and unique details, political dynamics, and supervisory gaps.

2. Calibrate Risk to Capacity: Reflect institutional and detection weaknesses in vulnerability scoring.

3. Institutionalize Ownership: Anchor the NRA in executive structures and delegate clear mandates.

4. Sequence Reforms Strategically: Build legal and institutional foundations before expanding oversight.

5. Link Law to Enforcement: Ensure legal tools are usable by prosecutors and FIUs.

6. Tailor Assistance: Align support with sectoral diagnostics and national development strategies.

Conclusion

Risk-based AML/CFT reform is more of a governance challenge than a compliance exercise. Ethiopia’s case demonstrates how transitional states can advance by adopting adaptive strategies and aligning institutions to test the effectiveness of operational tools and drive replicable progress. As global financial threats evolve, the path to effective implementation lies in aligning context, capacity, and collaboration. For peer countries, the key lesson is clear: transforming compliance into capability requires phased reform, strategic investment, and committed leadership.

Nolawi M. Engdayehu is a public policy advisor with broad experience in AML/CFT strategy, regulatory reform, and institutional resilience in transitional settings. He led Ethiopia’s second National Risk Assessment (NRA) and sectoral reviews, supporting the design of supervisory frameworks and inter-agency enforcement mechanisms. His broader work spans governance, geopolitics, risk assessment, and disaster risk management (DRM) within the context of foreign and regional policy.