30

May

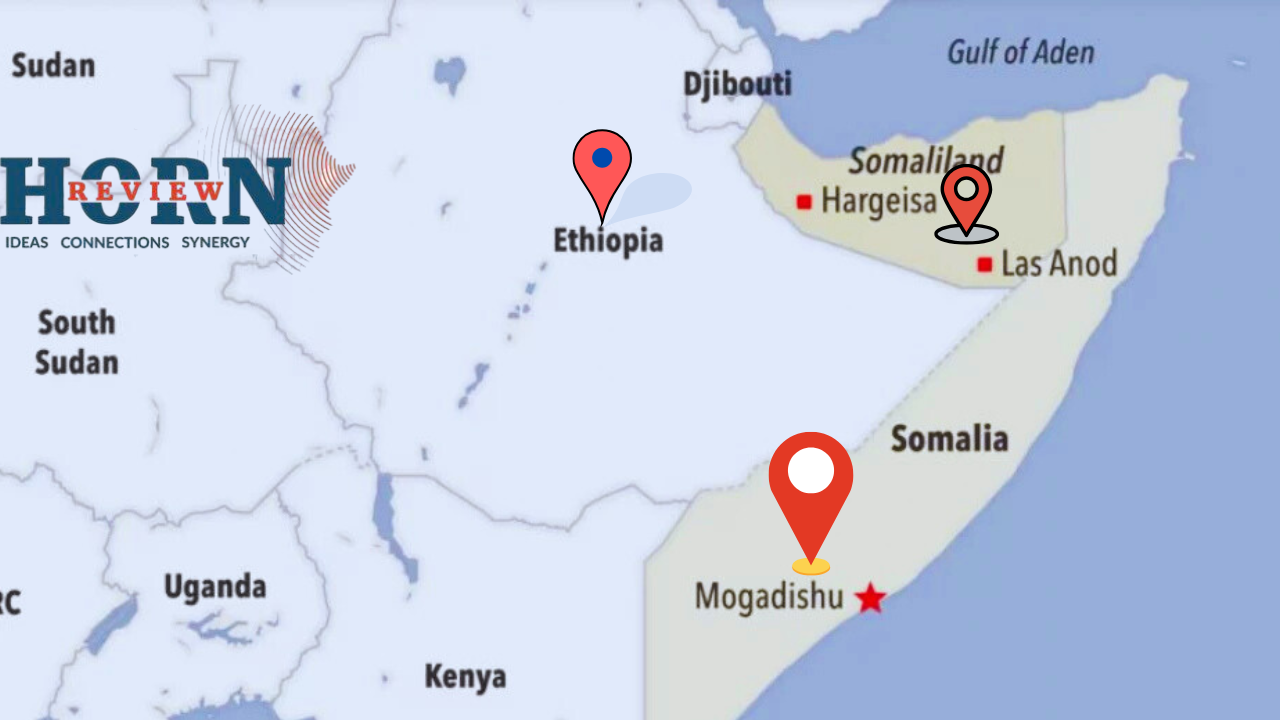

Ethiopia’s Forward Posture: Realigning with Both Mogadishu and Hargeisa

By Nolawi M. Engdayehu

In a previous analysis, “Reshaping the Red Sea: Centering Ethiopia in Regional Security,” Nolawi Engdayehu argued for a recalibrated foreign and security policy that places Ethiopia at the heart of regional dynamics. This follow-up shifts the lens to the Horn itself, where the unresolved tensions between Mogadishu and Hargeisa demand a forward-looking Ethiopian posture — one that is pragmatic, dual-tracked, and underpinned by national interest.

The political divorce between Mogadishu and Hargeisa has long since hardened into a de facto separation — a durable, if unrecognized, arrangement. Despite decades of diplomatic overtures, this division has resisted resolution and now constitutes a geopolitical constant. Since declaring independence in 1991, Somaliland has steadily asserted its statehood, conducting elections, maintaining internal stability, and forging functional external relations with regional and global actors alike.

This is no longer a temporary rupture. It is a deeply entrenched reality — one that traditional diplomacy has failed to overcome and that should not be ignored. Somaliland functions as a state in every meaningful sense, despite the absence of international recognition.

Meanwhile, the federal government in Mogadishu has not only failed to reintegrate Somaliland but also lacks significant political leverage over its governance. The symbolic stalemate over recognition remains, but it does little to shape the region’s day-to-day security, trade, and governance dynamics.

In this context, Ethiopia must shape its foreign policy around pragmatic realism rather than symbolic aspirations. A balanced and constructive engagement with both Mogadishu and Hargeisa is not only timely but integral to advancing regional stability, economic interdependence, and security. Addis Ababa must proactively communicate this dual-track approach to Mogadishu as both necessity and non-negotiable. Both relationships are vital to Ethiopia’s enduring interests and cannot be viewed as mutually exclusive. With a strategically realistic outlook, Somalia’s foreign policy could reframe this dynamic as a shared opportunity for regional cooperation, rather than a point of contention.

Ethiopia, whose peace and prosperity are deeply intertwined with regional dynamics, must engage with the prevailing realities while remaining mindful of the aspirations of all its neighbors. Addis Ababa cannot afford to let the unresolved Mogadishu–Hargeisa dispute define the boundaries of its foreign policy or jeopardize its national security imperatives. With over 120 million people, an economy constrained by imposed containment from direct sea access, and pressing infrastructure and security needs, Ethiopia must engage with both Somalia and Somaliland in parallel — pragmatically and with clarity of purpose.

Somalia’s objections to Ethiopia’s engagement with Hargeisa, often framed in the language of sovereignty, are understandable. Yet they must evolve into a broader, more forward-looking approach to regional diplomacy that calculates how stronger relations with Ethiopia might benefit Somalia itself. Ethiopia is not undermining Somalia’s sovereignty; the sovereignty issue predates and exists independently of Ethiopia’s engagement. Rather, Ethiopia is forced to deal with overlapping regional priorities. This is less a challenge to Somalia’s integrity, and more a reflection of the region’s complex realities — and the need for practical responses to them.

The idea that Ethiopia’s foreign policy should be constrained by the complex and unresolved question of Somali unity is increasingly difficult to justify. The realities on the ground speak for themselves: more than three decades of stalled negotiations, steady institutional development in Somaliland, and a gradual international engagement that reflects Somaliland’s de facto autonomy. While Mogadishu maintains its formal position on unity, its approach has, in practice, allowed space for Somaliland to cultivate partnerships with global powers. The UAE’s investment in Berbera port continues to expand beyond mere economic partnership, while the UK’s increased assistance and the U.S.’s security cooperation illustrate the pragmatic realism many actors have taken in response to these evolving dynamics.

Ethiopia’s regional engagement must mirror this pragmatism. Its interests in Somaliland — including maritime access, trade integration, and regional security coordination — require a clear-sighted and timely policy approach. Somaliland, by virtue of its existing commercial, geographic, and cultural ties with Ethiopia — as well as its relative institutional capacity — presents a logical and credible partner. This, however, does not diminish the importance of Ethiopia’s relationship with Mogadishu. Both Ethiopia and Somalia stand to benefit significantly from robust cooperation on trade, counterterrorism, and regional security. These partnerships serve different but complementary national objectives. Advancing cooperation with Somalia should not preclude Ethiopia from cultivating an equally vital relationship with Hargeisa. The overarching goal must be a balanced, parallel policy approach — not a zero-sum calculus.

Recent attempts by Mogadishu to frame Ethiopia’s engagement with Somaliland as antagonistic — including implied warnings of destabilization or invoking security threats such as Al-Shabaab — are deeply concerning. Such rhetoric risks undermining regional trust and cooperation at a time when stability is sorely needed. Notably, similar warnings have not been issued to other countries that have expanded ties with Somaliland, underscoring the politically selective nature of these objections. Linking legitimate diplomatic relations to the specter of extremism not only weakens Somalia’s own position but inadvertently empowers actors who threaten all states in the region. Responsible regional diplomacy must reject tactics that conflate bilateral engagement with insecurity. Shared threats from extremism should unite, not divide, the region’s stakeholders.

Ethiopia must remain clear-eyed and resolute: it will continue to deepen ties with Mogadishu, recognizing the importance of state-to-state relations and the mutual benefits of sustained cooperation. At the same time, it should pursue a parallel and equally significant partnership with Hargeisa — one that is neither subject to Mogadishu’s veto nor constrained by its domestic political anxieties. Policy circles in Mogadishu must come to the realization that the region cannot afford to let unresolved disputes stall any forward momentum.

This does not mean ignoring Somalia’s sensitivities. Ethiopia must communicate — with clarity and consistency — that its strategic priorities and security cannot remain hostage to a reconciliation that has eluded resolution for over three decade. As part of its new “Horn First” doctrine — a fundamental shift in foreign policy that prioritizes deeper subregional engagement — Ethiopia should pursue an open and unapologetic partnership with Hargeisa. This relationship must reflect not only Ethiopia’s urgent national priorities around regional integration, but also acknowledge the decades-long aspiration of Somalilanders to move beyond the political limbo they have endured since reclaiming independence in the early 1990s.

Somaliland — beyond the current maritime discourse — is a historically intertwined, geographically proximate, and strategically aligned partner whose role in Ethiopia’s regional calculus is both self-evident and indispensable. As other international actors have done — from the UAE to the UK and the United States, Ethiopia must now formalize this partnership through transparent and mutually beneficial agreements.

If approached with strategic realism and diplomatic creativity, this moment offers a rare opportunity: a new model of coexistence among Somalia, Somaliland, and Ethiopia. One that respects political differences while promoting regional integration, stability, and shared growth. Rather than deepen rivalries, Ethiopia’s approach could help redefine the Horn’s diplomatic landscape.

What Ethiopia cannot afford is inaction — postponing access to vital trade routes, hesitating on economic integration, or compromising its regional security posture in the hope that a political breakthrough between Mogadishu and Hargeisa will eventually materialize. The cost of delay is steep: enduring economic constraints, growing security risks, and a diminishing ability to shape the strategic, political, and economic architecture of the region on its own terms.

Ultimately, Ethiopia must ground its Horn of Africa policy in reality — not on aspiration. Nearly every possible strategy to operationalize foreign policy in the region is being tested by the unresolved and persistent rift between Somalia and Somaliland. Yet, how neighboring states choose to respond to this impasse will either entrench regional stagnation or chart a path beyond it.

Ethiopia’s choice lies in engaging decisively where there is opportunity — not merely where there is precedent.

Nolawi M. Engdayehu is a senior policy analyst focusing on the Horn of Africa. He has worked with international organizations, governments, NGOs, think tanks, and diplomatic missions on regional peace and security, advocacy, governance, disaster risk management, and related cross-cutting policy areas.