30

Apr

The Fork in the Road: How Divergent Paths Shaped Ethiopia and Eritrea

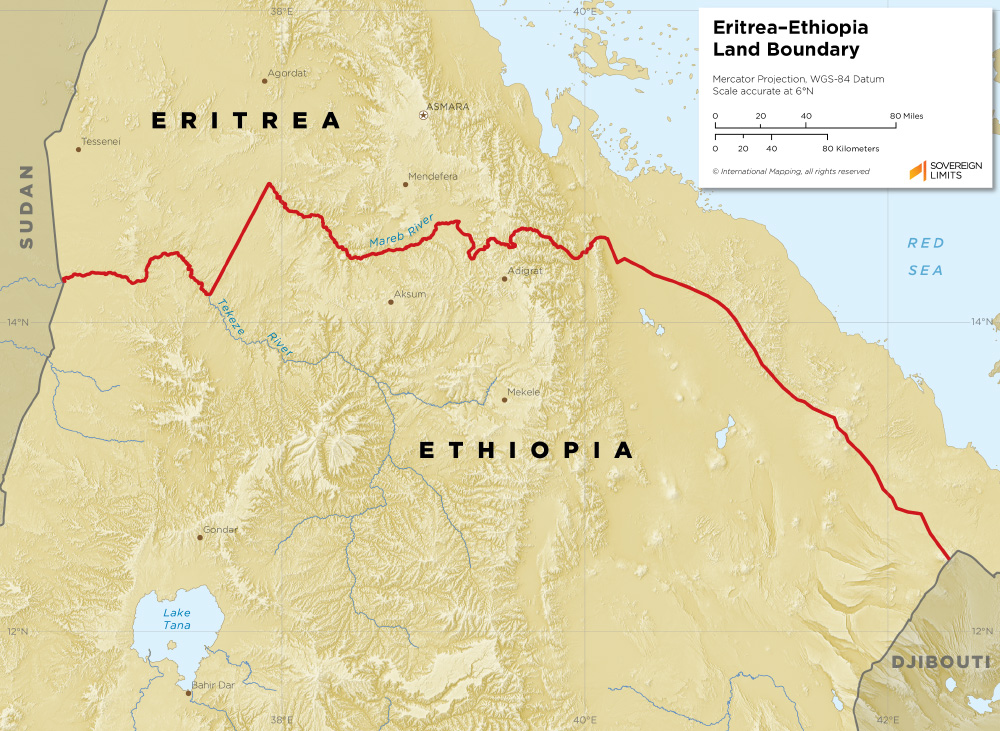

The Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) emerged from the crucible of Marxist-inspired resistance against the Derg regime in Ethiopia during the 1970s. Born of similar ideological parentage and a shared enemy, these two movements only contrasted in their mission. The EPLF’s unwavering objective was the secession and establishment of an independent Eritrea, while the TPLF initially focused on liberating the people of Tigray from what it deemed as the domination within a unified Ethiopia. The fall of the Derg in 1991 marked a pivotal juncture, a fork in the road that would lead these once-allied movements down drastically different trajectories, ultimately shaping the contrasting realities of Ethiopia and Eritrea today.

As the dust settled after the Derg’s demise, the TPLF, at the front of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) coalition, seized control of Addis Ababa. It went on to fundamentally reshape Ethiopia’s political architecture, ushering in an era of ethnic federalism. In Asmara, the EPLF celebrated Eritrea’s hard-won independence in 1993, embarking on its own nation-building project.

Ethiopia, under the EPRDF, embarked on a journey of institutional development, albeit one often criticized for its authoritarian tendencies. A new constitution formalized the ethnic federal structure. While the EPRDF maintained a firm grip on power, it had within its ranks a coalition resembling pluralism. Regular elections, though often marred by irregularities, were held, and opposition parties, however constrained, were legally permitted to exist. Civil society, despite facing limitations, carved out pockets of space. The EPRDF, while dominant, fostered a system that, at least on the surface, allowed for the gradual evolution of state institutions and the rotation of administrations.

Eritrea, under the spearheading leadership of Isaias Afwerki and, the EPLF’s successor, the People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ), chose a dramatically different route. The 1997 constitution, intended to lay the foundation for a democratic state, was never implemented. Elections, beyond the initial independence referendum, became a distant memory. The PFDJ solidified its position as the sole legal political entity, effectively establishing a rigid one-party dictatorship. The promise of a democratic Eritrea evaporated as the nation remained in a perpetual state of emergency. The crushing of the “G-15” reform movement in 2001, where cabinet ministers advocating for democratic reforms were jailed and silenced, laminated the air of authoritarianism, casting a long shadow over Eritrean society for decades to come.

The contrasting approaches extended beyond political structures into the realm of economic policy. Ethiopia, under PM Meles’s developmental-state model, embraced foreign partnerships and investment. Roads, railways, telecommunications, and energy infrastructure witnessed significant expansion. The government actively courted Ethiopian diaspora remittances and sought international partnerships. This strategy yielded impressive results, with the country achieving world recognized GDP spikes.

Eritrea, in stark contrast, adopted an almost diametrically opposed economic philosophy. Guided by a deep-seated suspicion of markets and a fervent belief in self-reliance, the PFDJ prioritized heavy militarization of the economy. Agriculture remained largely subsistence-based, and private enterprise faced severe constraints. The imposition of a controversial 2% “diaspora tax” on Eritreans living abroad became a significant source of state funding.

The costly border war between the two countries at turn of the century yielded contrasting results. For Eritrea, it drained already scarce resources and pushed the PFDJ further into isolation. While Ethiopia continued to see economic growth and increased courtship in global stages.

The divergent paths in state formation and economic management profoundly impacted the political and social landscapes of both nations.

Ethiopia, despite its authoritarian tendencies, cultivated a pool of technocrats and administrators drawn from diverse backgrounds. The EPRDF populated government ministries with educated managers, engineers, and economists. The expansion of schools and universities produced a growing number of graduates. While civil society faced restrictions, a degree of pluralism found room to develop. Professional associations and NGOs operated, and public debate, particularly among the diaspora and youth was prevalent. Even when the regime responded repressively to periods of unrest, the underlying institutional framework allowed for the eventual elevation of new leaders.

Eritrea, however, witnessed a reversal of any initial post-independence gains in social development. While Eritrea saw progress in education during the liberation struggle, the PFDJ, in fear of dissent actively repressed the sector. By the early 2000s, the indefinite conscription of secondary school teachers into the army crippled the education system. Higher education suffered a significant blow with the dismantling of the University of Asmara into smaller technical institutes. Academics and journalists faced imprisonment or were forced into exile.

With the repression of ideas, the consequence was a society where intellectual discourse was stifled, and opportunities for advancement were severely limited. Repression prevented the development of normal civilian careers and fuelled a mass exodus of young Eritreans seeking possibilities elsewhere.

A pivotal moment that starkly illustrated these contrasting trajectories was Ethiopia’s leadership change in 2018. Faced with widespread protests demanding political reform and an end to ethnic marginalization, the ruling EPRDF, despite its initial reluctance, eventually responded to public pressure. The resignation of Hailemariam Desalegn paved the way for the selection of Abiy Ahmed as the new Prime Minister. Abiy’s ascendance followed a shift within the ruling class structure of Ethiopia. The Prime Minister, who himself developed within the EPRDF, was able to draw from a pool of civil servants and politicians, who grew out of the space the previous government had allowed and fostered.

Eritrea, in stark contrast, offers no such signs of political change or renewal. President Isaias Afwerki remains firmly entrenched in power, operating in a space empty of any opposing voices. His one-party rule offers no vision for change to a repressed society. Instead, dissent is largely met with further repression, and the country’s institutions remain frozen in time. The absence of any discernible succession plan and the suppression of any internal reform movement paint a bleak picture for Eritrea’s future, particularly in a post-Isaias era.

The long-term consequences of these divergent paths are undeniable. Ethiopia, despite its ongoing challenges including ethnic tensions and unrest, continue to foster a society with greater opportunities in education, economic activities, and political mobility. The growth of universities, the expansion of the middle class, and the continuous ascendance of fresh and young faces in leadership has contributed to a more dynamic and outward-looking nation.

Eritrea on the other hand, has suffered from a significant drain of its youth as they flee from the oppressive conditions and lack of opportunities. The suppression of civil society and the absence of a free press continue stifle public discourse and innovation. The rigid control exerted by the PFDJ has left the nation isolated and facing a precarious future, devoid of a clear path going forward.

Ethiopia’s relative openness to the emergence of new, educated leaders and its willingness to engage with change have positioned it on a path to successfully face the challenges posed by the dawn of a new world.

Eritrea, under the ossified rule of its founding generation, has remained locked in a state of stagnation and isolation. The failure to cultivate new leadership and the systematic suppression of societal development have left Eritrea facing a challenging future, particularly as the long shadow of Isaias Afwerki’s rule eventually lifts.

The fork in the road taken in the aftermath of the Derg has irrevocably shaped the destinies of these two nations, leaving Ethiopia with the capability of eyeing the future and Eritrea mired with the challenges of stagnation and decay.