11

Feb

Kenya’s Nile Imperative: Why Ratifying the CFA Is Essential for Region Solidarity and Basin Leadership

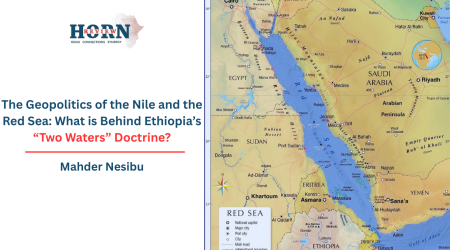

Standing on the misty banks of the Nzoia River in western Kenya, watching its waters carve through Kakamega’s lush forests before merging into the endless blue of Lake Victoria. This isn’t a torrent like Ethiopia’s Blue Nile gushing from highland plateaus, but a steady, life-sustaining flow one of several Kenyan rivers, including the Yala, Nyando, Migori, and Mara, that quietly feed the White Nile system. These streams might contribute a smaller share to the Nile’s overall volume, but they play an irreplaceable role: regulating lake levels, nurturing fisheries and farmlands for millions in Kisumu, Homa Bay, Busia, and Migori counties, and providing a natural buffer against the wild swings of climate. For too long, colonial-era agreements like the 1929 Anglo-Egyptian Treaty and the 1959 Nile Waters Agreement have overshadowed this reality, handing downstream giants Egypt and Sudan near-absolute control while upstream nations like Kenya lingered on the margins, their voices muted and their needs ignored. The Nile Basin Cooperative Framework Agreement (CFA), which Kenya signed in 2010, changes that story entirely.

With principles of equitable use, no significant harm to neighbors, open data sharing, and plans for a permanent Nile River Basin Commission (NRBC), the CFA offers a modern path to shared prosperity. Seven riparian states have ratified it, bringing the framework to life. Kenya stands as the notable holdout among early signatories, a hesitation often whispered to stem from fears of Egyptian backlash. Yet in today’s Horn of Africa, where Kenya’s alliance with Ethiopia runs deeper than rivers forged in mutual defense pacts and celebrated at milestones like the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) inauguration, ratification isn’t optional. It’s a must. Even with modest water contributions, Kenya is undeniably part of the Nile Basin family. Holding back weakens Kenya’s hand and forfeits a seat at the table where the basin’s future is shaped.

Kenya’s connection to the Nile runs deeper than maps suggest, embedding it in a web of interdependence that demands formal commitment. Lake Victoria, cradling Kenya’s western shores, isn’t a static pond but a dynamic regulator of the Nile’s pulse. Kenyan tributaries swell its waters during rainy seasons, easing outflows through the Owen Falls into Uganda and beyond, while in dry times they help maintain levels critical for fisheries that feed communities and hydropower that lights homes. Climate change has turned this balance into a high-stakes situation.

Remember the 2022-2023 drought that shrank the lake, crippling fish hauls and straining power grids? Or the 2020 floods that turned Nyando Valley roads into rivers, displacing thousands? Kenya copes through patchwork efforts, bilateral talks with Uganda, projects under the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI) but these lack the binding force to truly coordinate. The CFA flips the script. It mandates real-time data flows across borders, turning isolated weather stations into a basin-wide early-warning network. Floods on the Mara could be predicted and managed jointly with Tanzania; droughts along the Yala buffered by shared reservoir plans.

Ethiopia’s GERD enters here as a perfect partner: its controlled releases from the Blue Nile could stabilize Kenya’s dry-season inflows, while Kenya’s lake management smooths the river’s temperament for Addis Ababa’s massive energy needs. Without ratification, these synergies remain gentlemanly handshakes, vulnerable to politics or mistrust. With it, Kenya steps into the NRBC as an equal architect, where hydrological science not historical grudges guides decisions. Kenya’s equatorial position gives it outsized influence on lake dynamics, turning modest streams into levers of basin stability. To stay out is to let others write the rules for waters that start in Kenyan soil.

This commitment unleashes a ripple of economic vitality, transforming water from a vulnerability into a springboard for growth. Envision irrigation networks threading from Migori’s highlands across borders to Tanzanian plains, channeling steady supplies to smallholder farms that now battle erratic rains. Or restored wetlands around Lake Victoria, cleared of choking water hyacinth, reviving fish stocks and eco-tourism draws. The NBI has planted seeds of cross-border weather upgrades linking Kakamega to Kampala, joint ecosystem fixes but these are previews.

Ratification elevates them to enduring infrastructure: reservoirs taming the Yala’s floods for year-round crops, power interconnectors funneling GERD surplus into Kenya’s industrial parks and Vision 2030 hubs. Kenyan leaders have already embraced this vision, praising the GERD not as Ethiopia’s alone but as a pan-African path, with talks of energy swaps lighting factories from Naivasha to Nairobi. Global funders, from the World Bank to African Development Bank, flock to such cooperative frameworks, preferring basin-wide plans over solo bids. Kenya becomes the natural connector equatorial gateway blending Ethiopian hydropower with its ports and markets. Western counties, long sidelined, bloom. It’s not about dominating the Nile; it’s about weaving Kenya’s threads into a tapestry of mutual gain.

Geopolitics sharpens the urgency, placing Kenya’s Ethiopian alliance front and center against lingering Egyptian concerns. The Horn simmers al-Shabaab raids from Somalia, Sudan’s civil strife spilling across borders, Eritrea’s quiet maneuvers. Amid this, Kenya and Ethiopia stand shoulder-to-shoulder, their defense cooperation agreement treating threats to one as threats to both: shared intelligence, joint exercises, fortified borders. Kenyan presence at the GERD inauguration wasn’t ceremonial; it was a pledge of solidarity, echoing vows for deeper energy ties and security weaves. Ethiopia’s push for Nile equity mirrors Kenya’s own quest: why cheer their dam publicly yet hesitate on the CFA that would lock in fair play?

Egypt’s shadow looms large, its historical Nile dominance fueling worries over upstream projects like GERD, leading to overtures toward Somalia and occasional chill in ties. Kenya paused ratification in 2018 amid such tensions, fearing fallout on trade or projects like Lamu Port. But that’s yesterday’s caution. The CFA builds bridges, not walls; its “prior consultation” clauses demand good-faith talks to prevent harm, exactly what’s de-escalated GERD debates recently. Ratifying reassures Cairo of Kenya’s balanced hand while honoring Addis, positioning Nairobi as IGAD’s trusted mediator in Ethiopia-Somalia talks or broader Horn frays. In a region where water disputes whisper into louder conflicts, Kenya inside the NRBC gains diplomatic muscle: a vote on rules, data to defuse crises, arbitration beyond bilateral spats.

Institutional power cements the case. Today, Kenya chats via NBI forums; ratification seats it at NRBC tables, shaping hydrological standards, dispute paths, and project blueprints. Uganda’s gains bolstered experts, policy sway, preview Kenya’s path: hydrologists versed in basin rhythms, voices steering GERD protocols or lake health. No more sidelines; Kenya authors its Nile chapter.

Risks fade on close look. Egyptian grumbles meet recent diplomacy and AU channels where Kenya shines. Small shares? Equity favors role over volume Kenya’s regulation is gold. Domestic politics align with pro-Ethiopia moves.

Kenya must ratify the CFA recently, Its rivers bind it to the basin; its people demand resilience; its economy hungers for growth; its Ethiopian bond requires fidelity. Fears of Egypt pale against these imperatives. In 2026’s promise GERD flowing, tensions easing, ratification births a stronger, united basin. The moment is ripe; Kenya must seize it, or watch destiny flow past.

By Rebecca Mulugeta, Researcher, Horn Review