9

Jan

Fractured Visions: The Saudi-UAE Schism and the Fragmentation of the Red Sea Order

The traditional architecture of Gulf cooperation, which once served as the silent arbiter of stability for the Red Sea corridor, has entered a phase of decline. As 2026 begins, the shared destiny once projected by Riyadh and Abu Dhabi has been replaced by an openly confrontational rivalry that is no longer confined to oil production quotas or managed diplomatic disagreements.

The definitive rupture arrived on December 30, 2025, when Saudi airstrikes targeted a UAE-linked weapons shipment in the Yemeni port of Mukalla, an act of kinetic intervention between nominal allies that signaled a shift from strategic divergence to active containment.

The core of this friction, according to a CNN report on January 5, 2026, is a fundamental disagreement over the preservation of state sovereignty versus the cultivation of sub-state fragmentation.Riyadh is reportedly increasingly wary of the UAE’s policies not only in the Horn of Africa but also in Syria, where it believes Abu Dhabi has cultivated ties with elements of the Druze community. These leaders have openly discussed secession, raising tensions over regional influence and political alignments that Riyadh views as a direct threat to the established state-centric order of the Middle East.

The Saudi alarm regarding the Druze community in southern Syria is not an isolated concern but reflects a broader pattern of Emirati statecraft.Analysts suggest that Riyadh views Abu Dhabi’s engagement with secessionist-leaning Druze leaders as part of a maritime empire strategy that prioritizes the empowerment of agile, non-state partners over centralized government structures. By fostering ties with autonomous entities in the Levant, the UAE creates a network of influence that is independent of, and often at odds with, the sovereign frameworks that Saudi Arabia seeks to preserve.

This Axis of Secessionists strategy is viewed by Saudi security circles as highly dangerous, mirroring the UAE’s support for the Southern Transitional Council (STC) in Yemen and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in Sudan. For Riyadh, which shares a 700-kilometer border with Yemen and faces its own internal stabilization challenges, the normalization of secession and the potential breaking of countries, for tactical gain, represents an existential threat to regional security and the integrity of national borders.

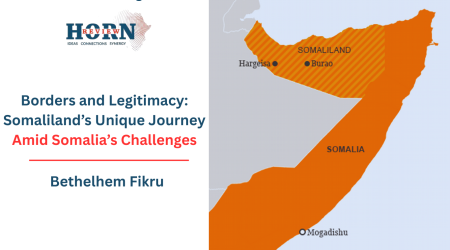

Moreover,the Saudi-UAE rivalry has metastasized across the Red Sea, where the Horn of Africa has become the primary laboratory for these competing geopolitical models. The recent recognition of Somaliland by Israel on December 26, 2025, a move allegedly facilitated by the UAE, has served as a fresh catalyst for this friction.

Saudi Arabia has positioned itself as the guardian of the federal framework in Mogadishu, rejecting Somaliland’s secession as a violation of international law. In contrast, the UAE’s $440 million investment in the Berbera Port and its direct engagement with the Hargeisa administration underscore its preference for autonomous zones that provide secure maritime access and logistical reach without oversight from the Somalia capital; this dynamic is further reflected in Abu Dhabi’s visa policy, under which Somaliland passports are accepted in the UAE’s visa system while visitors holding Somali passports are effectively barred from new visas beginning in 2026, a move interpreted by some analysts as signaling deeper political alignment with Hargeisa’s de facto authorities.

A troubling dimension of the 2026 crisis is the role of disinformation and intelligence failures. CNN’s reporting indicates that the recent escalation in Yemen may have been fueled by false information provided to the UAE, claiming that the Saudi Crown Prince had lobbied the U.S. government to impose sanctions on Abu Dhabi. While Riyadh has reportedly reached out to clarify that no such request was made, the damage to institutional trust has proved significant, prompting the UAE to mobilize its proxies in the eastern Yemeni provinces of Hadramawt and al-Mahra as a tactical retaliation.

For the nations of the Horn, this Gulf schism represents both a danger and a strategic opening. The risk is a “Sudanization” of regional disputes, where local actors play Riyadh and Abu Dhabi against each other to secure weaponry and funding, leading to a durable partition of territory.

However, the tentative emergence of a counter-alignment involving Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Egypt introduces an alternative—though not unproblematic—set of external engagements for Horn states. While Riyadh and Ankara have increasingly emphasized state cohesion and territorial integrity as organizing principles of regional order, Cairo’s involvement remains driven by narrower strategic calculations, particularly concerning Nile hydro politics and Red Sea security. As such, this alignment cannot be read as a uniformly integrationist bloc, but rather as a convergence of overlapping and at times competing interests that Horn states must navigate with caution.

For the states of the Horn, the priority must therefore be the consolidation of collective bargaining power through regional institutions such as the African Union (AU) and IGAD, ensuring that external rivalries do not erode local governance or instrumentalize internal divisions for geopolitical gain.24 The establishment of a Regional Technical Committee on border governance, alongside the pursuit of multilateral port-sharing and transit agreements, represents a pragmatic pathway toward reducing structural dependency on zero-sum Gulf rivalries and unilateral security patronage.

The Saudi–UAE rivalry has thus evolved beyond a contest for economic primacy into a struggle over the political geography of the modern Middle East and Africa. The reported Saudi unease regarding Emirati engagement with Druze actors in southern Syria underscores a growing perception in Riyadh that Abu Dhabi’s foreign policy trajectory is fundamentally destabilizing to the state-centric order Saudi Arabia seeks to preserve.

As 2026 unfolds, the stability of the Red Sea region will hinge on a decisive binary: whether Riyadh and Abu Dhabi can discipline their rivalry through calibrated diplomacy and mutually recognized red lines, preserving a fragile but functional regional order, or whether the continued instrumentalization of sub-state actors and coercive power politics will entrench fragmentation, normalize secessionist precedents, and lock the Horn of Africa into a prolonged cycle of instability that erodes the very foundations of sovereignty and regional integration.

By Tsega’ab Amare, Researcher, Horn Review