17

May

Why President Trump Should Take His Peace-making Initiative to the Horn of Africa

Now back in office, President Trump has intensified his trademark “deal-making” approach, engaging states across the Middle East, Asia, and Europe in pursuit of nuclear, trade, and ceasefire agreements. As the 45th President, his tenure included several commendable diplomatic efforts. Namely, through the Abraham Accords, he facilitated the normalization of Israel’s relations with four Arab states. He also famously worked out an agreement that opened the door to ending America’s long involvement in Afghanistan.

In his second term, by actively seeking resolutions to conflicts around the world, Trump appears determined to cement his legacy as a prolific broker of peace. At the U.S.-Saudi Investment Forum during his recent tour of the Gulf, he articulated a powerful vision for the Middle East. He praised the Gulf as a model of regional progress, describing it as a symbol of transformation from conflict to commerce.

“Before our eyes,” Trump said, “a new generation of leaders is transcending the ancient conflicts of tired divisions of the past and forging a future where the Middle East is defined by commerce, not chaos… where people of different nations, religions, and creeds are building cities together, not bombing each other out of existence.” He emphasized that this transformation had not come from Western interventionists, who, in his words, only fueled destabilization, citing examples like Kabul and Damascus.

Trump’s words raise a timely question: Can his administration extend this peace-making vision to the Horn of Africa?

The parallels between the Middle East and the Horn are compelling. Primarily, both share significant cultural, societal, and economic potential. In addition, much like the Middle East, the Horn’s persistent challenges are closely tied to the prevalence of geopolitical tensions and internal divisions.

The Horn of Africa could indeed benefit from an American leadership genuinely sympathetic to the region’s longstanding struggles with war, economic stagnation, and weak institutions. With Trump’s peace-focused vision, the people of the Horn, weary and tired of conflict, may find an ally in pursuing meaningful development and stability.

For reasons Trump himself highlighted in his talk at Riyadh, past Western involvements in the Middle East, similar to those in the Horn, have largely failed. First, Western policies have largely been “interventionist” and “neo-colonial,” as he described them. They were often implemented with little understanding of the complex socio-political fabric of non-Western societies. Their frequently offered one-size-fits-all solutions often fail to address the ground’s layered realities.

In addition, predominantly in the past 3 decades, war was often a strategic tool in Western realpolitik. Interventionism was frequently used in conflicts to secure geopolitical objectives. Trump, despite employing force in instances like airstrikes on the Houthis to “restore navigation”, has consistently rejected war as a preferred strategy. His general aversion to hard power makes him a unique candidate for peace diplomacy.

Trump’s style of diplomacy is also unique from another lens. His approach is almost contradictory to the established peace-brokering frameworks, which are often slow, bureaucratic, and bound by rigid diplomatic formalities and institutional processes. Trump sees himself as pragmatic and prefers swift, direct action. His reliance on executive orders and top-down implementation at home is a reflection of a leadership style that avoids the inefficiency of traditional state channels. This approach may make him more responsive and effective in conflict resolution efforts, particularly in regions where urgency and clarity are paramount.

The same motivations that drive Trump’s Middle East policy, which are strategic interest and economic opportunity, apply equally to the Horn. Trump’s engagement with the Middle East is primarily transactional. With regards to the global south, he primarily sees economic potential and is less concerned about asserting power. Unlike past U.S. administrations that emphasized military and political dominance, Trump is focused on business and the potential for mutual benefits.

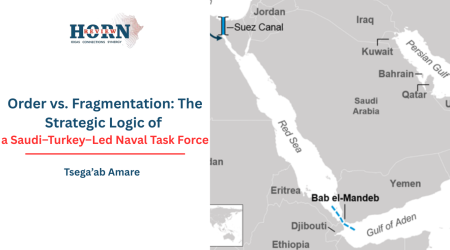

The Horn offers precisely that kind of strategic value. It sits at a critical junction along the Red Sea, a vital maritime artery for global trade. Reducing hindrances through these waters, which manifested his clash with the Houthis, is central to Trump’s stated interests. Rather than relying on military action, as seen in Yemen, he could engage directly with governments in the region to stabilize and secure this crucial zone through diplomacy and economic partnership.

Additionally, a stable Horn of Africa could emerge as a valuable trading partner for the US. Just as the Gulf states have become important players on the global economic stage, the Horn holds immense untapped potential. With the right investment and political will, its latent capabilities could be harnessed, with the U.S. poised to position itself as a leading ally.

Trump’s philosophy aligns with this potential. “My priority is to end conflicts, not start them. I will never hesitate to wield American power, if necessary, but I hate war,” he once said. Nowhere is conflict more prevalent than in the Horn, where cycles of violence have led to chronic instability and suffering. If Trump chooses to act on his convictions, his administration could play a pivotal role in breaking this cycle and paving the way for peace.

Yet, despite these compelling arguments, there are reasons to be sceptical. Trump’s approach to Africa has largely been rooted in indifference. His cabinet and State Department have shown limited engagement with the continent, except for South Africa, arguably motivated by the wrong reasons. His transactional approach may find little immediate value in a region whose economic potential is still largely unrealized.

Furthermore, the complexity of the Horn’s security and political landscape may be beyond Trump’s preferred style of diplomacy. He is often criticized for favouring “quick fixes” over nuanced, long-term strategies. The war in Ukraine has highlighted his limitations in dealing with layered international challenges that require patience and multilateral coordination.

Nonetheless, even if unlikely, Trump’s renewed presidency might still prove to be a blessing for the Horn of Africa. The vision he laid out in Riyadh, of a Middle East overcoming its historical burdens to embrace peace and prosperity, mirrors the very conundrum that continues to plague the Horn. Should President Trump shift his attention to this region, the beginning of real progress may no longer be a distant dream.

By Mahder Nesibu, Researcher,Horn Review