20

Jan

The Hydro-Political Pivot: Deconstructing the “Trump Corollary”

The diplomatic correspondence issued by the White House to President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi on January 16, 2026, represents a calculated attempt to resurrect a failed hydro-political order under the guise of American mediation. Coming just twenty-four hours after reports emerged that Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Somalia were finalizing a new military coalition, the timing of the letter reveals what may be termed a “Trump Corollary” to Horn of Africa diplomacy: a transactional framework that trades Ethiopian development for Egyptian cooperation in the Middle East.

By praising el-Sisi’s role in brokering the October 2025 Gaza ceasefire, the Trump administration seeks to launder the image of a leader once described as its “favorite dictator” into that of a pivotal “man of peace.” This manufactured moral authority is then leveraged to extract concessions on the Nile. Such transactional logic, which treats African resources as bargaining chips for Middle Eastern security, ignores the foundational shifts that have reshaped the Nile Basin’s legal landscape, most notably the entry into force of the Nile Cooperative Framework Agreement (CFA) on October 13, 2024.

A line-by-line reading of the letter reveals a narrative designed to legitimize Egyptian existential anxieties while steadily eroding the legitimacy of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), formally inaugurated in September 2025. When the letter calls for resolving the question of “Nile water sharing once and for all,” it deliberately invokes the language of the colonial-era 1929 and 1959 agreements treaties that marginalized Ethiopia and which Addis Ababa has never recognized.

Ethiopia has consistently maintained that the Nile is not to be “shared” in a zero-sum sense, but governed through the principle of equitable and reasonable utilization. By reverting to the vocabulary of “sharing,” the United States signals a return to the biased mediation framework of 2020, which sought to impose volumetric caps that would have effectively constrained Ethiopia’s industrial and developmental trajectory.

The letter’s assertion that “no state in this region should unilaterally control the precious resources of the Nile” is conceptually flawed. The GERD is a hydroelectric project funded entirely by the Ethiopian public and constructed within Ethiopian territory, on a river that contributes approximately 86 percent of its flow from the Ethiopian highlands. To characterize Ethiopia’s management of a domestic, non-consumptive energy project as “unilateral control” is to imply that Addis Ababa requires external permission to utilize its own natural resources.

Equally problematic is the claim that Ethiopia “disadvantages its neighbors.” This assertion collapses under empirical scrutiny. During the GERD’s filling phase from 2020 to 2024, despite repeated alarmist appeals by Cairo to the UN Security Council, Egypt experienced no measurable reduction in water levels at the Aswan High Dam. On the contrary, a combination of above-average rainfall and Ethiopia’s calibrated filling strategy ensured that downstream reservoirs remained at or near optimal capacity.

The oft-invoked “existential threat” narrative thus functions as a manufactured crisis, deployed by the Egyptian state to obscure its own chronic water mismanagement. Egypt reportedly loses roughly 25.7 percent of its potable water through infrastructural leakage and up to 50 percent of its agricultural water due to inefficient flood-irrigation practices. Rather than addressing these structural deficiencies, Cairo has externalized responsibility for its mounting water stress onto Ethiopia’s non-consumptive hydroelectric project.

Historically, Egypt’s Nile policy has been characterized by hegemonic monopoly, frequently at the expense of its downstream partner, Sudan. For decades, Cairo entrenched its claims through bilateral arrangements such as the 1959 agreement, concluded without the consent of other riparian states and often privileging Egyptian storage imperatives over Sudanese development needs.

This legacy of exclusion what may be described as fragmentation as ratio imperii, or fragmentation as a technique of rule has seen Egypt consistently obstruct basin-wide legal integration in favor of divided, non-binding mechanisms. The entry into force of the CFA and the subsequent establishment of the Nile River Basin Commission (NRBC) by Ethiopia, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Burundi, and South Sudan has dismantled this colonial-era veto. It has created a new legal reality that both Egypt and the United States now appear intent on circumventing.

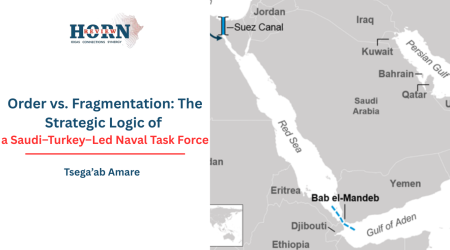

The broader regional realignment, exemplified by the emerging Saudi-Egypt-Somalia military bloc, must be understood within this context. This alignment is, in part, a response to Ethiopia’s assertive pursuit of maritime access and its evolving partnerships with the UAE and Somaliland.

By offering mediation on the Nile, the Trump administration effectively provides diplomatic cover for this encirclement strategy. Egypt gains leverage at the negotiating table while its allies exert pressure on Ethiopia’s territorial and maritime interests along the Somali front. This is a stark exercise in realpolitik, in which the developmental rights of over 120 million Ethiopians more than half of whom still lack reliable access to electricity are subordinated to the perceived stability of an authoritarian regime in Cairo.

Ethiopia’s optimal counter-strategy must therefore rest on a doctrine of principled sovereignty, anchored in the long-standing commitment to “African Solutions to African Problems.” Addis Ababa should acknowledge Washington’s stated interest while firmly asserting that the Nile is now governed by the legally constituted NRBC, thereby neutralizing attempts to forum-shop the dispute back to external capitals.

At the same time, Ethiopia should actively challenge the “unilateralism” narrative by proposing a basin-wide transparency and efficiency audit that exposes systemic water losses and infrastructural failures downstream. By framing the GERD as a stabilizing asset that mitigates floods and buffers droughts, and by linking its maritime ambitions in Somaliland to the broader imperative of Red Sea security, Ethiopia can convert perceived geopolitical isolation into a position of indispensable regional leadership one that upholds both sovereignty and cooperative basin governance.

By Surafel Tesfaye, Researcher, Horn Review