7

Jan

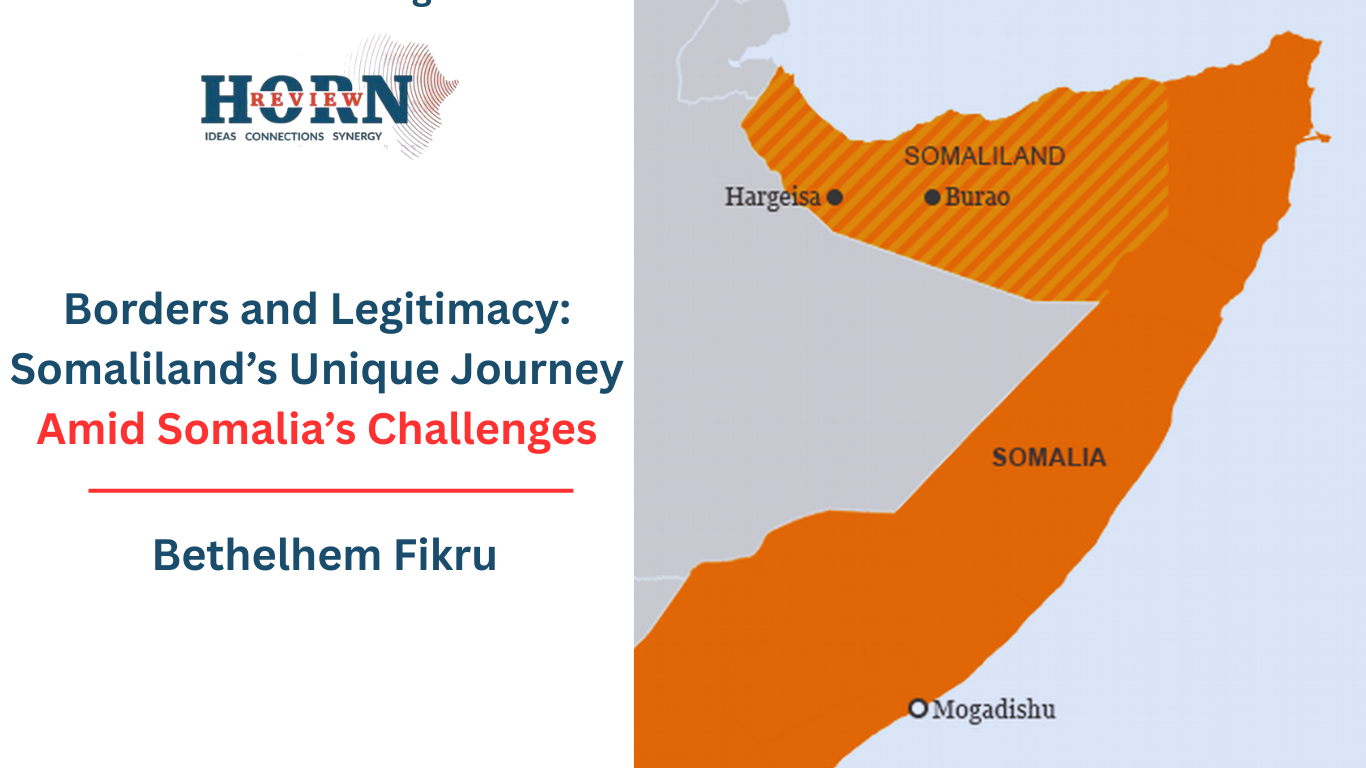

Borders and Legitimacy: Somaliland’s Unique Journey Amid Somalia’s Challenges

In early 2026, Somalia remains a deeply fragile state facing persistent political and security challenges. As the federal government’s mandate approaches its expiration in May, proposed electoral reforms aimed at introducing universal suffrage have generated opposition from several clans and federal member states, including Puntland and Jubaland, raising concerns about political legitimacy. At the same time, the continued presence and resurgence of Al-Shabaab in parts of south-central Somalia highlight the federal government’s limited capacity to exercise effective control. Ongoing governance challenges, including poor performance on corruption indices and persistent human rights concerns, further illustrate Somalia’s institutional fragility. This situation stands in marked contrast to Somaliland, which has functioned as a de facto state since 1991 and has maintained relative stability, conducted multiple democratic elections, and pursued economic development through strategic infrastructure such as the Berbera port. Somaliland’s claim is framed not as secession but as the restoration of its 1960 independence, positioning it as a distinctive case within African political history that continues to prompt debate over recognition.

Somalia’s troubles trace back to colonial partitions that divided Somali peoples across British, Italian, and French. Upon independence in 1960, the Somali Republic pursued irredentist “Greater Somalia” dreams, seeking to annex Somali-inhabited regions in Ethiopia’s Ogaden, Kenya’s Northern Frontier District, and Djibouti. This expansionism directly led to the 1964 Ethiopian-Somali Border War, where Somali forces invaded Ogaden, killing thousands and displacing civilians. Somalia’s aggression stemmed from rejecting colonial borders, viewing them as barriers to ethnic unity. At the Organization of African Unity (OAU)’s 1964 Cairo Summit, Somalia (alongside Morocco) was one of only two nations to oppose Resolution AHG/Res. 16(I), which enshrined the inviolability of inherited colonial borders to prevent continental conflicts. Somali leaders argued borders clashed with self-determination, fueling irredentism that destabilized the Horn of Africa.

This historical context adds complexity to Somalia’s contemporary reliance on the same border principle now enshrined in Article 4(b) of the African Union Constitutive Act to oppose Somaliland’s recognition. Somaliland, formerly British Somaliland, achieved independence on June 26, 1960, and was recognized by 35 states, including all permanent members of the UN Security Council. It voluntarily entered into union with Italian Somaliland on July 1, forming the Somali Republic, although the union was never formally ratified. Over time, governance imbalances and political breakdown contributed to state collapse. In 1991, Somaliland reasserted its independence within its pre-union boundaries, characterizing the move as the restoration of sovereignty rather than secession. While southern Somalia experienced prolonged conflict and institutional collapse, Somaliland pursued reconciliation through locally led clan conferences, establishing a hybrid political system that combined traditional authority with competitive elections.

The African Union’s 2005 fact-finding mission to Somaliland further acknowledged this distinct trajectory. Led by Deputy Chairperson Patrick Mazimhaka, the mission concluded that Somaliland’s case was “historically unique and self-justified in African political history,” noting that the unratified 1960 union had resulted in “enormous injustice and suffering.” The mission emphasized that Somaliland’s situation did not represent a precedent for widespread fragmentation, but rather the dissolution of a failed voluntary union. While the report did not constitute formal AU consensus, it highlighted the extent to which Somalia’s prolonged dysfunction placed additional burdens on Somaliland. The decision not to act on the report reflected institutional caution rather than a substantive refutation of its findings.

Subsequent AU statements have reflected varying perspectives among member states. AU Chairperson Mahmoud Ali Youssouf rejected Israel’s recognition of Somaliland, reaffirming the principle of territorial integrity and emphasizing Somaliland’s status as part of Somalia. However, this statement may not necessarily represent the views of all AU members and could reflect particular considerations associated with Djibouti, given Youssouf’s nationality. It does not imply a fully unified continental position, particularly as some member states maintain engagement with Somaliland on matters of security and economic cooperation. These differing approaches suggest that concerns over precedent continue to influence the AU’s collective deliberations.

Israel’s recognition of Somaliland in late 2025 renewed international discussion, including a UN Security Council session . During the debate, Israel’s representative highlighted what was described as a historical inconsistency, noting that Somalia had previously opposed the principle of border inviolability during its irredentist period, yet now invokes it in opposition to Somaliland’s claim, which is grounded in the restoration of pre-1960 borders. While several Council members cautioned against actions perceived as destabilizing, the exchange reflected broader questions about consistency in the application of international norms.

Somalia’s historical trajectory demonstrates how prolonged conflict, institutional collapse, and governance challenges have shaped regional dynamics. Somaliland, by contrast, has developed functioning institutions and sustained stability over three decades. Somaliland meets the core criteria of statehood outlined in the Montevideo Convention, including a permanent population, defined territory, effective government, and capacity to engage externally. Proponents argue that recognition could contribute to regional stability, enhance trade through Berbera, and align with the findings of the AU’s own fact-finding mission, without encouraging broader fragmentation. Somalia’s ongoing challenges, while deserving of international support, need not indefinitely constrain Somaliland’s political future.

In conclusion, historical experience highlights divergent paths taken by Somalia and Somaliland. Somaliland’s case, grounded in historical specificity and sustained governance performance, continues to raise legitimate questions within African and international diplomacy. Revisiting the African Union’s 2005 findings with renewed objectivity would allow policy to reflect realities on the ground rather than inherited anxieties. Recognition of Somaliland need not be viewed as a challenge to African unity, but as an opportunity to align principles with practice. Until this exceptional case is addressed on its merits, the Horn of Africa risks remaining constrained by unresolved legacies rather than guided by pragmatic pathways toward peace, stability, and regional prosperity.

By Bethelhem Fikru, Researcher, Horn Review