30

Dec

Can India be the second country to recognize Somaliland?

The question of whether India could become the second country to recognise Somaliland is no longer a purely hypothetical exercise. It sits at the intersection of deep colonial-era linkages, evolving Indian Ocean geopolitics, and a rapidly intensifying great-power competition in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden. What makes the India Somaliland file particularly intriguing is that the two are not merely distant entities who might discover each other for the first time; they share a layered historical relationship dating back to the British Empire, a mutually relevant Indian Ocean maritime space, and converging interests in trade security and energy routes. If India were ever to contemplate recognition, it would not emerge in a vacuum. It would be rooted in a past where British Somaliland looked eastward more than southward, in a present where Berbera’s port is again being reimagined as a strategic gateway, and in a future where India’s aspirations as an Indo-Pacific and African power demand bolder, sometimes disruptive, diplomatic choices.

Under British colonial rule, British Somaliland and British India were not isolated peripheries. Rather, they were functionally linked nodes of the same imperial system, connected through commerce, administration, and military logistics across the Indian Ocean. While London was the formal imperial centre, the practical gravitational pull for British Somaliland was often India. During the colonial period, British authorities drew heavily on Indian labourers, traders, and administrators to operate imperial outposts like Berbera. Indian merchants dominated commerce in Berbera, acting as key intermediaries in import and export operations, credit provision, and retail. The economic life of British Somaliland was thus deeply entangled with Indian commercial networks, and local Salamanders often found themselves dealing more frequently with Indian traders and shop owners than with British officials. The circulation of Indian rupees in Somaliland’s economy underlines this integration. The rupee was not just a currency; it signified a shared monetary and commercial space that spanned from the Subcontinent to the Horn of Africa. Trade, trust, and credit were structured around Indian financial norms and practices, establishing a form of economic interdependence well before either entity gained post-colonial autonomy.

Administratively, the British also deployed Indians to handle the paperwork and bureaucratic routines of the empire. These Indian clerks and officials helped shape aspects of local administration in British Somaliland, leaving an imprint on how governance and record-keeping were conducted. This arrangement reflected a broader pattern in which the British used India as an imperial hub: troops, administrators, and commercial expertise flowed from Bombay and Aden to smaller protectorates like Somaliland. Militarily, Indian troops also played a role in securing British Somaliland. Units from Aden and the Bombay infantry were involved in protecting the territory and safeguarding sea routes that were vital for Britain’s connection to India. Strategically, British Somaliland functioned as a logistical link to Aden and, by extension, to India. The eastward route to India and Aden mattered more for British Somaliland than deeper southward integration into the Somali hinterland.

Yet despite this functional integration, Indian and Somali communities often lived apart. They maintained distinct social identities, even while their economic roles were intertwined. These dynamic, separate communities, linked economies reflected the broader Indian Ocean trading world, where Indian merchant diasporas formed semi-autonomous enclaves in ports from East Africa to the Gulf, without dissolving into local societies. In effect, British Somaliland was governed differently from India but functionally linked through India within the British imperial system. India was the practical centre of gravity for Somaliland’s trade, currency, bureaucratic staffing, and military logistics more than distant London was. These colonial-era ties did not disappear overnight after independence; they left behind habits of economic interaction, shared commercial memory, and a sense in some circles in Somaliland that India was a familiar, if indirect, partner.

After independence and the formation of the union between Somaliland and Somalia, India kept a low diplomatic profile in the Somali territories. India tended to view the Horn of Africa through broader African or Indian Ocean lenses rather than as a primary foreign policy strategy. However, a low profile did not mean total absence. India’s engagement often flowed through non-traditional and non-diplomatic channels. Somalilanders sought education in India, building personal and professional networks that cut across the Gulf and East African circuits. Informal commercial ties continued through Gulf ports, East African trading communities, and Indian Ocean shipping lines, maintaining a subtle but real interdependence between Somalilanders and Indian networks.

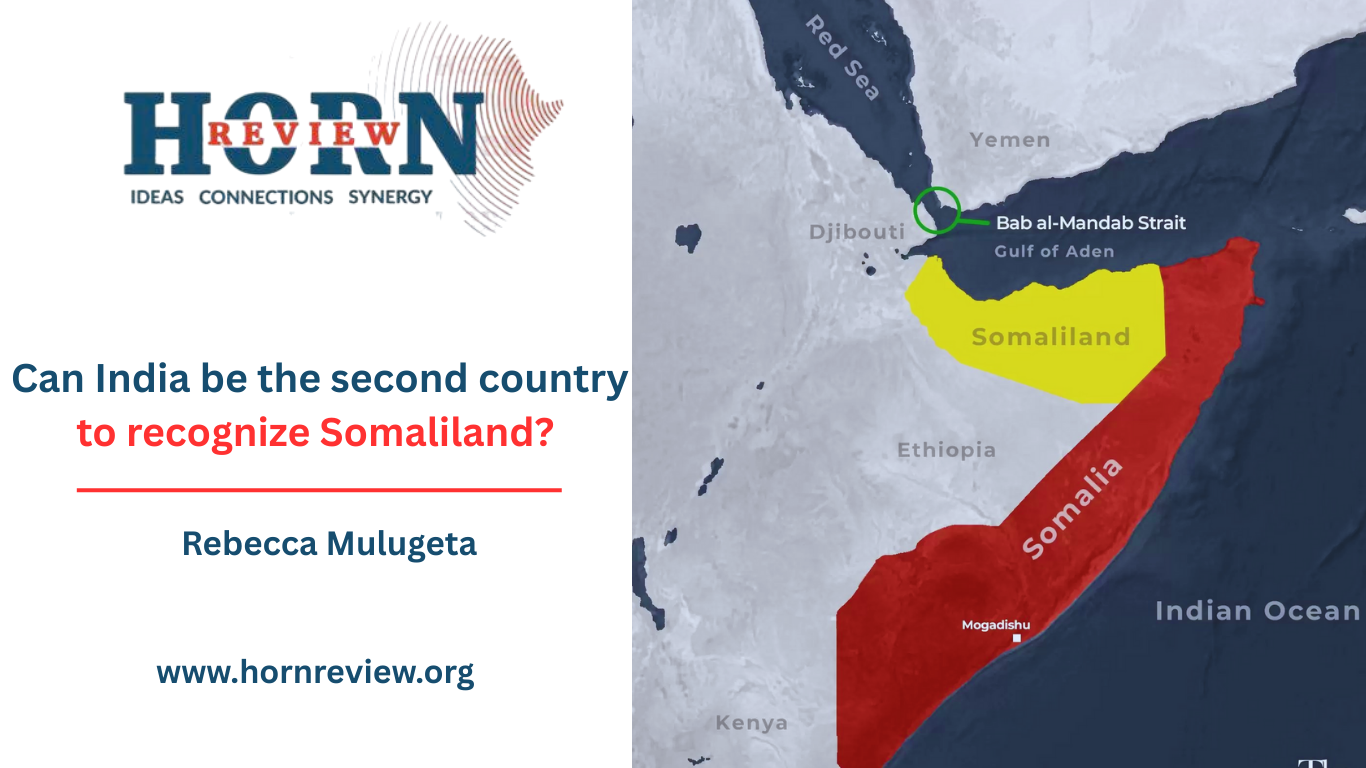

Diplomatically, India has historically maintained liaison-style contacts rather than full, high-visibility engagement. From New Delhi’s perspective, Somaliland has been viewed as a “functional society without legal status”: a de facto state with effective authority, but without international recognition. This cautious stance reflected India’s own sensitivity to separatism and territorial integrity issues. Yet, as Somaliland continues to function as a de facto state for over three decades, the practical gap between recognition and reality is becoming harder to ignore for actors who prioritise stability and predictable partners in volatile regions. The heart of the contemporary strategic argument lies on the coastline. The Gulf of Aden and the Bab el-Mandeb strait form one of the world’s most critical chokepoints, connecting the Indian Ocean to the Red Sea and onward to Europe via the Suez Canal. For India, whose trade with Europe and Africa increasingly transits these waters, any instability or hostile presence in this corridor directly affects its energy security and trade flows.

The region around Somaliland is now crowded with external powers. China has established its first overseas military base in Djibouti, symbolising its ambition to project power beyond Asia and secure its own maritime lifelines. Turkey has expanded its military and political presence in Somalia and elsewhere in the Horn. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has invested heavily in ports and bases along the Red Sea corridor, including Berbera. Meanwhile, insurgent actors such as Yemen’s Houthi movement and maritime threats like piracy and smuggling complicate the security environment. For India, this presents both a challenge and an opportunity. India does not want to be squeezed out of a maritime struggle that is central to its long-term Indo-Pacific vision. It cannot afford to see key ports, logistical hubs, and politically stable partners dominated by China, Turkey, or other rival or competitive actors. This is where Berbera and Somaliland re-enter India’s strategic imagination.

Berbera, upgraded with Emirati investment and linked increasingly to Ethiopia’s large and growing market, is poised to become an important regional trade hub. Rail and road projects under discussion or development aim to connect Berbera to Addis Ababa and potentially to broader East African hinterlands. In this context, India’s recent efforts to deepen ties with Ethiopia, symbolised by visits and partnership agreements, including under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s tenure, indirectly touch Somaliland. If India wants to be a serious economic and strategic player in the Horn, it cannot ignore a port that could reshape trade routes into Ethiopia and the broader region.

Somaliland’s relative stability compared to the chronic volatility in southern Somalia further strengthens its appeal. For over 30 years, Somaliland has maintained internal order, managed its borders, and administered its ports, operating as a de facto state in an otherwise fragmented environment. For a risk-averse but opportunistic foreign policy like India’s, this predictability is valuable. India’s strategic culture generally avoids high-risk security entanglements, but it will engage where a partner is stable, cooperative, and aligned with its broader security and economic objectives. In that sense, Somaliland fits many of India’s practical criteria.India’s maritime strategy in the western Indian Ocean revolves around several core interests: securing sea lanes of communication, protecting energy imports, expanding trade, and balancing competitor states. The Red Sea–Bab el-Mandeb–Gulf of Aden corridor is crucial for Indian energy imports from the Gulf and trade with Europe and parts of Africa. Any disruption from insurgent groups, regional wars, or great-power rivalries has direct implications for India’s domestic economy.

Somalia’s southern political landscape is complex, with deep-rooted conflicts, federal disputes, and insurgent threats. Engaging heavily there is politically sensitive and operationally challenging. By contrast, Somaliland offers a more straightforward, coherent interlocutor, albeit one without formal international recognition. India also faces intensifying competition from China and Turkey in Africa. China’s presence in Djibouti, its Belt and Road investments, and its military and economic reach across the continent create a strategic environment in which India must actively secure its own footholds or risk marginalisation. Turkey’s assertive role in Somalia and elsewhere adds another competitor in a region where India cannot rely solely on diplomatic rhetoric.

In this struggle for influence, recognition of Somaliland would be a bold, disruptive move. It would signal that India can act independently of Western caution and traditional diplomatic inertia, secure a friendly, relatively democratic, and stable partner on a strategic coastline, gain a stronger say in port and infrastructure projects that intersect directly with Ethiopia and the wider Horn, and counterbalance actors by anchoring a long-term relationship with a polity that has reasons to value India’s support. India under Narendra Modi has already demonstrated a willingness to take decisive and controversial steps in sensitive geopolitical arenas, including in economic and diplomatic confrontations with major powers. The logic of an “India that acts” rather than an “India that only reacts” could, in theory, extend to recognition of Somaliland if the strategic benefits are judged to outweigh the risks.

There is another layer, more political than geographic, that could shape Indian thinking: the positions of Pakistan, Turkey, and Qatar on Kashmir and Somalia. These states have tended to support Pakistan’s stance or criticise India’s policies in Kashmir and, at the same time, often back the Somali Federal Government’s claim over all Somali territories. From an Indian perspective, this creates a potential field for diplomatic counter-moves. If countries publicly challenge India’s territorial position in Kashmir while also supporting a central authority in Mogadishu that is often aligned with Turkey, Qatar, and others, India may be tempted to consider steps that impose reciprocal diplomatic costs.

India’s growing partnerships with the UAE and Ethiopia open space for trilateral or minilateral frameworks that implicitly bring Somaliland into the picture. The UAE is already heavily involved in Berbera’s development, and Ethiopia is a primary beneficiary of that port’s expansion. India’s desire to enhance trade and strategic cooperation with both countries creates an indirect trilateral logic: the UAE provides capital and commercial know-how in port and logistics operations, Ethiopia supplies the hinterland market and political weight in the Horn, and India contributes market access, technology, security cooperation, and political leverage within the wider Indo-Pacific and Global South. Even if India does not immediately recognise Somaliland, a gradual deepening of trilateral engagement, port security, trade corridors, and infrastructure financing could normalise Somaliland’s status in practice. Over time, this could create the conditions for formal recognition, especially if other major players begin to move in that direction or if the costs of non-recognition outweigh the diplomatic friction with Mogadishu and the African Union.

Yet, the balance is shifting. Somaliland has functioned as a de facto state for over 30 years, manages its own security and borders, and offers far more predictability than the rest of Somalia. In practice, many international actors already treat Somaliland differently, even if they stop short of recognition. Given India’s bolder strategic posture under Modi and the growing urgency of Indian Ocean and Red Sea security, it is conceivable that India may, at some point, conclude that the strategic, economic, and political benefits of recognising Somaliland outweigh the costs. If one major state, perhaps a Gulf power or an African state, were to cross the recognition threshold, India might see an opening to become the “second mover,” gaining credit for decisiveness while avoiding total isolation.

Today, that shared past, combined with the strategic significance of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, creates a compelling case for a renewed relationship. Somaliland offers India a relatively stable, democratic, and strategically located partner in a region crowded by competitors and threatened by insurgent and maritime insecurity. Berbera connects directly to the trade and energy routes that matter most to India and into Ethiopia’s vast market. If India chooses to recognise Somaliland, it would be a bold move consistent with the more assertive foreign policy posture of the Modi era. It would signal that India is willing to shape the geopolitical map, not just adapt to it; that it can use historical linkages as strategic assets; and that it is ready to contest the expanding footprint of China, Turkey, and others in the Horn of Africa and the wider Indian Ocean world. The question is no longer whether there is a strategic logic for India to recognise Somaliland. There clearly is. The real question is when, and under what regional conditions, India’s cautious pragmatism will give way to a decisive act that aligns its Indian Ocean ambitions with the long-standing reality on the ground in Hargeisa and Berbera.

By Rebecca Mulugeta, Researcher, Horn Review