30

Oct

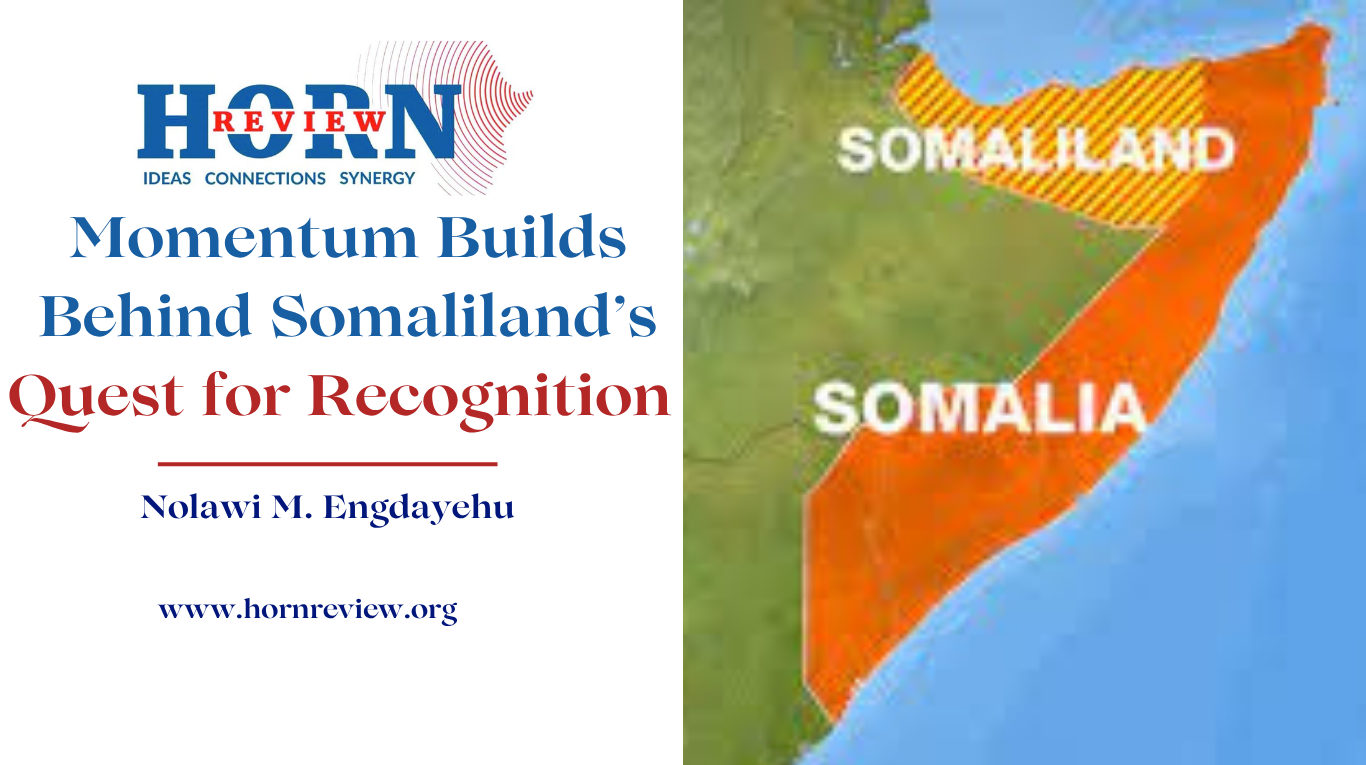

Momentum Builds Behind Somaliland’s Quest for Recognition

By Nolawi M. Engdayehu

After more than three decades of operating as a de facto state, Somaliland’s campaign for international recognition is entering a new phase. What once seemed an isolated regional issue has become part of a broader strategic conversation in Western policy circles. In Washington, Brussels, and London, Somaliland’s case, built on its record of stability, effective governance, and constructive regional engagement, is drawing more serious attention than ever before.

Somaliland’s lobbying in the United States and Europe has grown markedly more organized and effective. A coordinated effort among diaspora groups, advocacy organizations, and sympathetic lawmakers has yielded tangible results: sponsored legislation in Congress, State Department policy reviews, and expanding bipartisan engagement in both chambers. Increasingly, members of Congress and the Senate frame Somaliland’s case not as a legal abstraction but as a pragmatic stability issue.

In parallel, Somaliland has begun to attract attention from influential policy institutes in Washington. The American Enterprise Institute, one of the capital’s leading conservative think tanks, recently featured a recommendation for a “Taiwan-style” engagement model with Hargeisa, one that stops short of formal recognition but integrates Somaliland into global trade, development, and security conversations. That such a recommendation was highlighted in a forum of AEI’s stature signals a subtle but notable shift: Somaliland is moving from being the subject of a sensitive and informal discussion to a focus of structured policy debate. In Brussels, too, Somaliland’s efforts are gaining ground among legislators and foreign policy committees that view its stability as a regional asset amid an otherwise fragile Horn of Africa.

Among Western capitals, the United Kingdom appears most poised to take the first decisive step toward recognition. With historical ties dating back to Somaliland’s brief independence in 1960, London’s engagement has deepened across economic, development and security channels. The UK government has increased its consultations with Hargeisa, and members of Parliament across party lines now urge an “update” to the UK’s policy to reflect realities on the ground.

More broadly, European governments appear less willing to echo Mogadishu’s anti-secessionist rhetoric. While still operating within the African Union’s framework, many acknowledge Somaliland’s record of democratic governance and internal stability. From a security perspective, policymakers recognize that a cooperative, predictable partner on the Gulf of Aden directly serves Europe’s strategic interests, especially in curbing irregular migration, countering terrorism, and safeguarding maritime routes.

Yet Somaliland’s pursuit of recognition encounters its strongest resistance not in Western capitals, but among regional and global actors whose strategic interests diverge sharply across the Horn.

Turkey, now the dominant external actor in Mogadishu, has spent the past decade cultivating deep social and economic capital in Somalia. Through extensive humanitarian programs, infrastructure projects, and direct security assistance, Ankara has become a de facto patron. In return, it has secured privileged access to maritime resources, port facilities, and strategic infrastructure—including sites linked to its space program. For Turkey’s leadership, preserving Somalia’s territorial integrity is an extension of its regional influence.

Egypt’s opposition, meanwhile, is driven by its rivalry with Ethiopia. Since Addis Ababa completed the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), Cairo has viewed Somalia’s coastline as a strategic frontier for countering Ethiopia’s ambitions to gain sea access. Egyptian military cooperation with Somalia and its deployment of troops in the region reflect this calculus. Recognition of Somaliland would undermine these interests by shifting maritime leverage northward.

For China, the issue carries a symbolic risk. Somaliland’s parallel with Taiwan, two self-governing entities operating outside the formal UN system, makes Beijing adamant about opposing any precedent for secession. The African Union’s continued adherence to the principle of inviolable colonial borders remains central to its position, yet regional policy debates and diplomatic exchanges increasingly point to a quiet re-examination of whether this doctrine still serves Africa’s evolving political realities.

As Somaliland’s diplomatic case gains traction, its strongest argument remains its internal stability, predictable governance, and record of peaceful democratic competition. Its institutions, though modest in capacity, consistently deliver accountability and the rule of law. For investors and international partners, this translates into a low-risk environment and a credible platform for long-term engagement.

The UAE’s increasing investment in Berbera reflects the strategic calculus behind Somaliland’s growing relevance. Emirati-backed projects, particularly the proposed rail link connecting Berbera Port to Ethiopia, demonstrate Abu Dhabi’s intent to anchor the Horn of Africa within its expanding Gulf–Red Sea commercial and security architecture. These ventures are instruments of long-term geopolitical design, shaping future trade corridors and spheres of influence.

Until recently, DP World’s Berbera portfolio that comprised a modernized port and upgraded highway system, lacked a dependable, high-capacity rail line extending into Ethiopia’s logistics network. As plans for that connection progress, Ethiopia stands to gain its first viable maritime alternative to Djibouti, easing its strategic dependence on a single corridor. For Abu Dhabi, it marks an expanded maritime footprint; for Addis Ababa, it highlights a secure access and strategic flexibility across the Horn.

For the United States and its partners, this evolving configuration offers a timely opportunity to rethink engagement along the Red Sea and western Indian Ocean corridor. A more structured partnership with Somaliland could advance shared priorities including secure navigation, stable trade routes, and predictable regional governance within an increasingly contested maritime domain.

For regional actors still resisting Somaliland’s recognition, the debate can no longer hinge on the semantics of sovereignty versus recognition. In practice, sovereignty in Somaliland has long been exercised; what remains is the international acknowledgment of a political and institutional reality that has endured for more than three decades. Three decades of lived sovereignty have shaped the political, economic, and social fabric of Somaliland. In today’s fluid global order, marked by shifting alliances and redefined regional interests, formal recognition appears less a question of if than when.

Somaliland’s civil society and diaspora continue to reinforce this momentum. A generation born and raised in a self-governing state, celebrating national days, holding elections, and studying in schools that teach a distinct political identity, views reunion with Mogadishu as undesirable. Mogadishu’s recent attempts to encourage opposition within Somaliland, including through the creation of the Khatumo region, have only strengthened public consensus in favor of recognition and institutional consolidation.

Recognition of Somaliland would not only fulfill the long-standing aspirations of its people and advance stability in a region defined by overlapping security and governance challenges. A sequenced approach focused on expanded diplomatic engagement and formalized development partnerships would acknowledge Somaliland’s distinct status while reinforcing effective governance and institutional predictability. Such incremental recognition would align with broader strategic interests in maritime security, counterterrorism, and Red Sea trade resilience, offering a pragmatic pathway to regional order.

Ethiopia and Kenya, in particular, should note the trajectory of U.S. and UK policy. Both maintain strong ties with Hargeisa and could take the initiative to expand joint programs and coordinate a regional pathway toward recognition. Doing so would not only anticipate an inevitable outcome but also allow Nairobi and Addis Ababa to shape a process that aligns with their own economic and security interests. Properly managed, recognition could reconfigure the Horn’s security architecture toward stability rather than rivalry.

Somaliland’s sustained pursuit of recognition and changing regional dynamics have now brought Hargeisa to the center of policy conversations once reserved for other Horn capitals. The question facing the international community is no longer whether to engage Somaliland, but how to do so responsibly, and how regional powers can lead a process that is both inevitable and stabilizing.