7

Jun

Eritrea’s Proxy Strategy and the Rising Threat to Ethiopian Stability

The spectre of renewed hostilities between Eritrea and Ethiopia has resurfaced with a degree not seen since the brutal border war of 1998–2000. Although the likelihood of a large-scale conventional war remains limited, the dynamics of a proxy conflict have gained new momentum. Recent developments, both in Asmara’s stance toward its neighbour and in Ethiopia’s internal security situation, have created a fragile environment in which indirect confrontation seems almost certain. Tensions that appeared to ease after the 2018 rapprochement between Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and President Isaias Afwerki have deepened beneath the surface. As the situation edges toward a zero-sum contest, Ethiopia’s internal dilemmas have been drawn into a broader Eritrean plan of indirect destabilization, preparing the ground for a dangerous proxy war.

When Prime Minister Abiy’s envoys travelled to Asmara in mid-2018, the region’s hopes for lasting peace felt strong. The historic handshake between Abiy and Isaias and the subsequent state reconciliation generated optimism that decades of hostility might be left behind. Yet the foundations of that agreement proved less stable than expected.

The subsequent war in Tigray, which pitted the Eritrean Army and the Ethiopian Government against the TPLF, marked the beginning of the end for the reconciliation. From Asmara’s point of view, the Pretoria terms did not achieve full dismantling of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), an outcome President Isaias had insisted upon. The Eritrean leader’s firm position on removing the TPLF entirely became clear almost immediately; continuation of a relationship for Isaias depended on Addis Ababa’s willingness to eliminate its former northern rival. In this sense, the Pretoria agreement faced enormous challenges since it was signed. Once the ink was dry, a series of reactions began to undermine the fragile peace that ended the brutal war.

In the months following Pretoria, the Amhara region emerged as one of Ethiopia’s most heavily armed and therefore most unstable areas. The mobilization that had supported Ethiopia’s campaign in Tigray had provided the Amhara Special Forces (ASF) with substantial weaponry and trained fighters. When the federal government, concerned about the risks of empowering regional militias, ordered the dismantling of all regional special forces, armed groups in the region felt threatened. The ASF and affiliated Fano militias saw their arms as essential for protecting the region’s interests after years of conflict.

Addis Ababa’s attempt to assert a monopoly over legitimate force was interpreted in Amhara as an effort to undermine regional autonomy. Consequently, resistance to disarmament grew, evolving into a scattered but persistent uprising. Although Fano’s lack of central coordination limits its overall effectiveness, it’s still causing significant insecurity in the region.

It was in this context of persistent local dissent that reports began to emerge of Eritrean support for these Amhara insurgent elements. Sources in Addis Ababa claimed that Asmara is secretly providing logistical aid in the form of arms, intelligence, and possibly training to those resisting federal authority. By supporting Amhara’s rebellion, Asmara aims to keep Ethiopia off balance, ensuring that Addis Ababa’s military would remain engaged on multiple internal fronts. Rather than risk a costly confrontation, Eritrean policymakers are directing their efforts towards exploiting Ethiopia’s internal divisions, increasing pressure through indirect means.

Meanwhile, the TPLF, formally a signatory to the Pretoria agreement, found itself at the centre of its own internal split. The faction led by Getachew Reda had stayed committed to the peace framework, willing to follow the conditions for disarmament and political integration. In contrast, the wing headed by Debretsion Gebremichael had viewed the Pretoria terms as a betrayal, an unacceptable concession to Addis Ababa that threatened the party’s control in Tigray. In the ensuing power struggle, Debretsion’s faction removed Getachew’s leadership.

Disappointed by what they saw as capitulation in Pretoria, the hardliners followed this up by quietly establishing a relationship with Eritrean officials across the boarder. The past relationship between Eritrea and the TPLF, once defined by fierce hostility, seems to be temporarily set aside in favour of a shared interest: forcefully challenging the Federal Government. From Eritrea’s viewpoint, these TPLF dissidents who are moving to rearm and reorganize offer a suitable means of destabilizing Ethiopia.

Surprisingly, the collaboration between the TPLF and Eritrea overlooks the widespread suffering inflicted by the Eritrean Defense Forces (EDF) during the Tigray conflict. The EDF’s operations in Tigray involved widespread killings, mass rape, and other severe violations against civilians. Nevertheless, within the TPLF, some see working with Asmara as a necessary compromise.

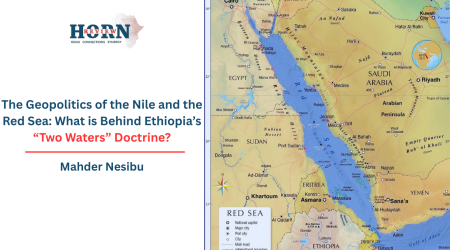

For its part, Asmara has never hidden its opposition to Ethiopia. In the recent Independence Day speech, President Isaias devoted an unusually large portion of his address to criticizing Addis Ababa, revealing Eritrea’s continued commitment to undermining its neighbour. Following Pretoria, Eritrea had pursued diplomatic ties with Egypt and Somalia, resulting in a tripartite memorandum of understanding aimed at countering Ethiopia’s influence. By forming this alliance, Eritrea aimed not only to surround Ethiopia but also to create channels for military and logistical support that could fuel a broader proxy campaign.

Contrary to countless estimations by international media, a direct clash between the Ethiopian Defense Forces and the Eritrean Army is still unlikely. Since the end of the Tigray conflict, Addis Ababa has heavily invested in modernizing and expanding its military capacities, acquiring advanced equipment and improving training with help from its international partners. The Ethiopian Defense Forces, once hindered by instability, now has a level of readiness that surpasses Eritrea’s limited conventional capacity. From Asmara’s perspective, therefore, provoking a conventional war risks a significant defeat. As a result, Eritrea’s strategic thinking has shifted toward intensifying proxy warfare, a method of weakening Ethiopia without risking a direct fight.

As Eritrea focuses on indirect methods, the Fano rebellion provides a limited but real way to create unrest. By supplying arms and possibly trainers to these groups, Eritrea aims to increase the rebellion’s disruptive power. Still, Fano’s fragmented structure limits its value as a proxy. Without centralized leadership or clear political plans, Fano cannot organize large-scale operations like a professional guerrilla force. Its value to Asmara, then, is primarily in causing local disturbances, incidents that aim to force the Ethiopian defence to spread its forces thin.

In contrast, the alliance between Eritrea and the TPLF hardliners poses a far greater threat to Addis Ababa. The TPLF, despite being officially excluded from Ethiopian politics, retains deep networks of support in Tigray and among parts of the Tigrayan diaspora. If these dissident members, supported by Eritrean logistics, decide to restart armed resistance, the federal government could face a renewed insurgency in the north. In such a situation, Tigray would become a battleground similar to the recent conflict, only this time with direct Eritrean backing. The prospect is especially worrying given the humanitarian crisis that accompanied the previous war. A new wave of fighting in Tigray, if backed by Eritrea, would not only threaten Ethiopia’s unity but also risk triggering a regional humanitarian emergency.

For the federal government, the top priority must be countering the combined influence of the TPLF–Eritrean alliance. While some observers continue to view Fano as the immediate source of instability, it is the organization and potential power of TPLF hardliners, emboldened by Asmara’s backing, that call for the greatest concern. The TPLF’s ability to draw on Eritrean logistics, along with its existing recruitment networks in Tigray, presents a danger that goes well beyond isolated insurgency.

The cooperation between Eritrean officials and TPLF hardliners thus represents the greatest threat to Ethiopia’s stability.

To maintain the peace achieved in Pretoria, it is essential that international actors remain aware of these evolving dynamics. The Ethiopian federal government must receive support in its efforts to persuade the TPLF to honour the Pretoria agreement. At the same time, there should be sustained diplomatic pressure on Eritrea to stop its backing of proxy forces, whether Fano militias in Amhara or dissident TPLF elements in Tigray. Without such coordinated action, the current pattern of indirect aggression risks destroying the tenuous peace of recent years and inviting a return to devastating conflict and humanitarian suffering. Only by urging Eritrea to desist from intervention and abandon proxy warfare could the region avoid another cycle of violence.

By Mahder Nesibu,Researcher,Horn Review