27

Oct

The Afar Question, Eritrea’s Secession and the Geopolitics of Ethiopia’s Lost Coast

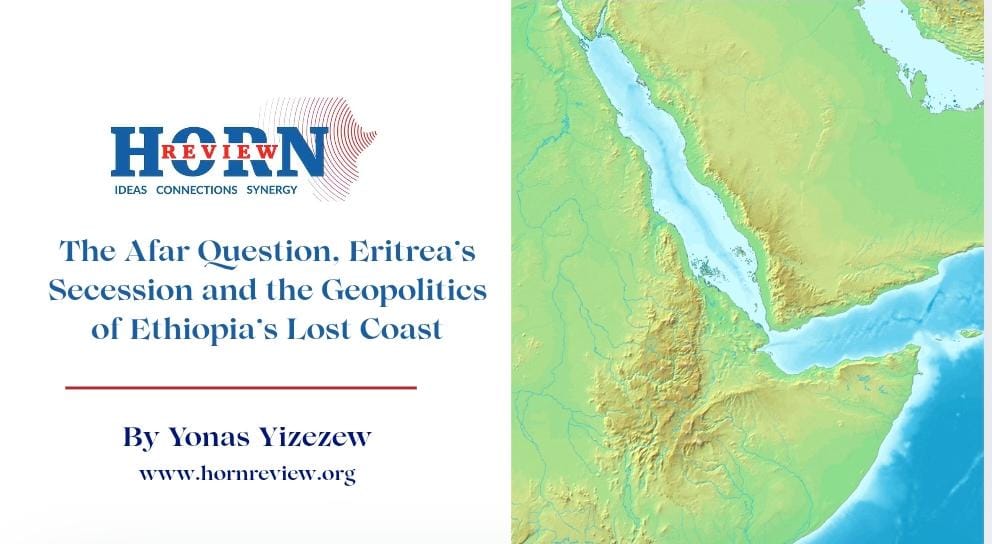

The Afar are among the oldest indigenous communities in the Horn of Africa, occupying a vast stretch of territory that spans modern-day Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Djibouti. Their land, historically unified and home to a largely nomadic and culturally coherent people, was tragically partitioned among these three states. Despite their anticolonial resistance, the Afar have continued to suffer further internal divisions and systemic marginalization imposed by the central governments of each country.

Despite this political fragmentation, the Afar have maintained a unified sense of identity rooted in kinship, language and shared pastoral traditions. The society always conceived of its territory as an indivisible whole, a concept often referred to as “Afar Land.” The Afar homeland lies along the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden, a region of immense geopolitical importance that has long drawn the attention of local and external powers.

However, the French control of Tadjourah, Italian conquest of Red Sea coast by the end of the 19th century, and the full incorporation of the Awussa Afar into Ethiopian Empire in the Post-Second World War period set the Afar in the Horn in different political structures and dispensations. Their land contains strategic resources, vital transport routes, and access to the ports of Assab and Djibouti, which have been central to Ethiopia’s economic lifelines and national security concerns. Yet the Afar people have remained politically marginalized, divided by borders that neither reflected their will nor served their collective interest.

Under Emperor Haile Selassie, the Afar were governed within five fragmented provinces. At that time, Afar leaders and sultans consistently advocated for their territories to be administered as a single region within Ethiopia. This aspiration for unity was viewed with suspicion by successive central governments in Addis Ababa. The prospect of a consolidated, politically conscious Afar region was perceived as a threat, a potential irredentist claim that could destabilize the empire’s delicate ethnic balance. This deep-seated fear of a “Great Afar” state became a constant undercurrent in the state’s relationship with the community. In the early 1970s, prominent Afar elders, religious figures, and clan chiefs petitioned Emperor Haile Selassie to unify the scattered Afar territories under a single administrative unit. The imperial government’s refusal deepened Afar grievances and reinforced the perception that the state regarded them as subjects rather than stakeholders in Ethiopia’s political order. This rejection catalyzed the politicization of Afar elites, giving rise to a nascent nationalist movement that soon crystallized into the Afar Liberation Front (ALF).

The Derg regime that replaced the monarchy introduced new promises under revolutionary reform. It recognized the concept of nationalities and granted limited regional autonomy. For the Afar, this briefly revived hope that their longstanding aspiration for unity would be addressed. But that hope was short-lived. In 1987, the administration declared the Assab Awraja a self-autonomous region and elevated Awssa district, leaving much of the Afar homeland divided and politically diluted. The Afar themselves opposed the Derg’s decision to elevate Assab as a separate entity, claiming that it would later expose them to dismemberment. Their fears proved justified when the Eritrean referendum disregarded their rights, cutting off Ethiopia’s historic maritime access and fragmenting Afar society.

When the EPRDF came to power in 1991, Ethiopia adopted a federal system that formally recognized ethnic-based regional states. The Afar were granted a regional state within this new structure. The dominant ruling parties (TPLF, ODP, ADP, etc.) relegated the Afar National Democratic Party (ANDP, which dissolved into the Prosperity Party in 2019) to ‘affiliate’ status, alongside other periphery regions. This relegation meant the Afar political elite were excluded from the core decision-making structure, leading to limited access to political resources.

However, the creation of Eritrea through the 1993 referendum altered the fate of the Afar people once again. The Red Sea Afar, who inhabited the long Red Sea coast, found themselves citizens of a new state that did not recognize their distinct identity or political rights. Many Afar argue that they were excluded from the referendum process that decided Eritrea’s secession. Testimonies suggest that international and regional actors, including TPLF and EPLF, played roles in engineering the separation without consulting the Afar communities whose lives it directly affected. In the aftermath, both the EPRDF in Ethiopia and the PFDJ in Eritrea pursued policies of neglect and containment towards their respective Afar populations.

The division of the Afar homeland by Eritrea’s separation produced deep social and economic ruptures. The Ethiopian Afar were cut off from Assab, their historic and economic outlet to the sea. What was once a short route to the coast became an extended detour through foreign territory. The Eritrean Afar, meanwhile, became one of the most repressed groups within the new state. Reports of forced displacement, political exclusion and systematic marginalization under the PFDJ (Eritrea) became common. Their access to land, movement, and livelihood along the coast were restricted, and many were subjected to imprisonment and persecution. Thousands fled to Ethiopia and Djibouti seeking safety and recognition.

However, the Ethiopian administration frequently categorized these displaced Afars as ‘Eritreans’ or ‘people expelled from Eritrea’. This administrative classification, classifying them by their origin from the new state rather than their ethnic and national desire, served as a powerful mechanism of political and economic exclusion. While they relied on informality and ethnic solidarity within the Afar region for survival, this limited economic viability and structural integration.

This outcome reflected a broader pattern of state behavior toward the Afar on both sides of the border. In Eritrea, the Afar were viewed with suspicion because of their transnational kinship and their perceived loyalty to Ethiopia. In Ethiopia, the EPRDF leadership remained wary of Afar nationalists’ irredentist tendencies, fearing that calls for the unification of Afar territories might threaten national cohesion. Consequently, the Afar region received limited investment and minimal political representation within the ruling coalition. Despite its strategic location and contribution to national security, the region lagged behind in development and governance participation. This double marginalization – by both Eritrea and Ethiopia – ensured that the Afar remained politically weak and economically disadvantaged.

Their historical ties to the port, their economic dependence on it, and the suffering they endured from its separation cannot be overstated. For Ethiopia to engage with this issue effectively, it must fundamentally shift its perception of the Afar. A genuine, inclusive political participation that acknowledges the Afar’s rightful place in the nation’s political life is not just a moral imperative but a geopolitical necessity. Given the internal political dynamics, regional geopolitics, and contemporary developments, it is essential to understand the situation and formulate approaches through the lens of the Afar people. The region’s future stability and any potential resolution of the port issue depend on partnering with the Afar people, recognizing their sacrifices, and finally honoring their long-standing quest for dignity, development, and a voice in their own destiny.

By genuinely empowering the Afar region, Ethiopia could secure a long-term, stable corridor to the sea that is politically supported by its inhabitants.

By Yonas Yizezew, Researcher, Horn Review