7

Oct

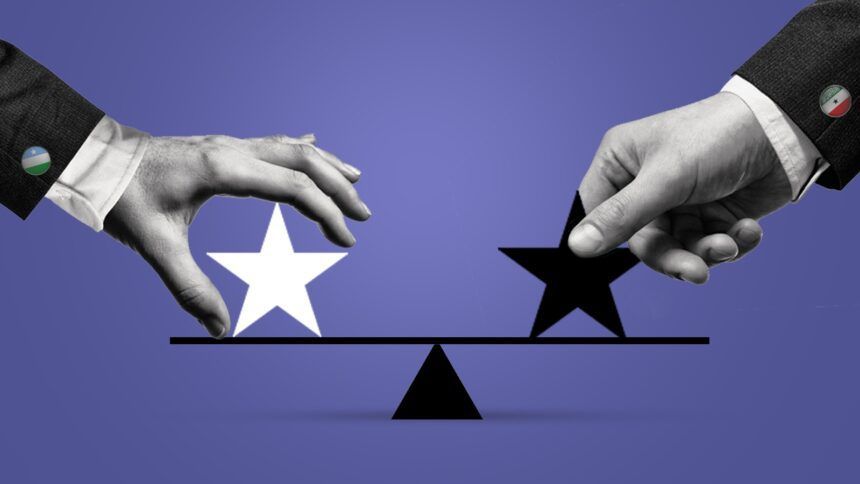

Somaliland’s Sovereignty Saboteurs: Is Somaliland’s Opposition Protecting A Principle Or Paralyzing Progress

In a historic recast for the Horn of Africa, the Republic of Somaliland and the Puntland Federal Member State of Somalia have signed a lodestar security and cooperation accord in Nairobi. This agreement aims to terminate decades of conflict over the disputed regions of Sool, Sanaag, and Cayn by establishing a new chassis for joint counter terrorism operations, maritime security, and cross border trade. To boot, beneath the surface of this diplomatic achievement, a domestic controversy is raging within Somaliland, centered on keen constitutional questions and a deep seated anxiety that the very sovereignty the nation has unremittingly pursued for decades may be subtly haggle away.

The accord has generated considerable domestic controversy, with a widely circulated critique attributed to former minister Dr. Abdiweli Soufi articulating a central fear that the agreement fundamentally obscures Somaliland’s claimed status as an independent republic. The opposition’s argument depends on the perceived violation of the nation’s constitutional sovereignty. The designation of Puntland, a Federal Member State of Somalia as a partner in overseeing peace efforts in Erigavo, a town within Somaliland’s own constitutional territory, is seen as an unacceptable cession of authority to an external entity. This critics charge erodes the foundational principle of Somaliland’s sovereign control over its affairs and dangerously blurs the lines between its claim of independence and Puntland’s status as a regional actor.

For a nation that has recently taken bold steps to assert full control over its aviation sector and engage with international bodies like the International Civil Aviation Organization , any agreement that might be interpreted as sharing this authority with Puntland is met with intense suspicion. The opposition argues that such arrangements undermine Somaliland’s state-building project and its carefully composed presentation to the world as a sovereign entity ready for formal recognition.

In response, the Somaliland government and its supporters have produced a defence to secure in realistic discretion. They contend that this criticism overlooks an irony, arguing that the Nairobi accord is a necessary and sensible attempt to manage the consequences of past failures, particularly the Las Anod crisis that unfurl under a previous administration, which they frame as a far more serious compromise of Somaliland’s territory. From this perspective, the agreement is not a surrender of sovereignty but a strategic recalibration.

The government’s narrative posits that the accord is a tool to stabilize restive regions through cooperation, thereby creating the conditions for Somaliland to eventually rebuild its influence. The commitment to joint operations against al-Shabab, a common threat, is presented as a logical step to enhance security for all citizens. Furthermore, by facilitating cross-border trade and supporting reconciliation in Erigavo, Hargeisa aims to address long standing economic and political severences that have been exploited by adversaries. In this view, the agreement is a tactical, forward-looking move designed to secure peace and create a more stable foundation from which to pursue the ultimate goal of international recognition.Somaliland’s territorial claims are shown in the principle of uti possidetis juris which the inheritance of the borders of the former British Somaliland protectorate. Puntland, conversely, has historically articulated its claims predicated on clan genealogy and kinship ties with the Darod clans inhabiting the disputed territories .

The Nairobi accord does not resolve this philosophical tension, but it introduces a seismic development. The clause in which Puntland formally welcomes Somaliland’s progress in Governance and its right to its self-determination is a diplomatic concession. For Hargeisa, this represents a critical legitimization of its statehood project by a key internal rival. For the opposition in Somaliland, however, this may bring a question if it comes at the cost of allowing that same rival a formalized role within its borders.

The resolution of this domestic crisis will not be found in a single act but through the arduous process of implementation. The central test for Hargeisa will be to manage the asymmetric risks inherent in the agreement. Puntland wields significant socio-political leverage within communities inside Somaliland’s constitutional borders, whereas Somaliland possesses no reciprocal influence inside Puntland proper. The government must therefore walk a diplomatic morass, leveraging the accord’s cooperative spirit to foster stability in regions like Sool and Sanaag without inadvertently ceding further political ground.

Ultimately, If cooperation with Puntland leads to enhanced security from al-Shabab, greater economic prosperity through trade, and durable local peace agreements, the government’s case will be powerfully strengthened. If, however, the partnership is perceived as weakening Somaliland’s sovereign authority or stoking internal divisions, the current constitutional anxieties will erupt with even greater force. The Nairobi agreement has opened a door to peace, but it has also ignited a vital, internal debate that will define the future of the Somaliland nation.

By Samiya Mohammed, Researcher, Horn Review