7

Jul

Historical Error and Political Remedy: The Afar Coast and Ethiopia’s Sovereign Right

“The Ethiopian Afar were the first to lose their sea before Palestine lost its coast.”

Long before Palestine lost its shoreline, before Gaza became a prison of ports, before the world cried out loud for lost coastlines in Palestine, decades before Gaza was blockaded in 2007, the Ethiopian Afar had already watched the Red Sea slip through their fingers after Eritrea’s 1998 secession. Their story, like that of the Palestinians, is a wound the world refuses to see: a people severed from their coast, erased from maps, and silenced in global discourse. Ethiopia became a nation caught between borders, forgotten in peace talks, and betrayed by maps drawn in European ink and African silence.

We are now talking about a homeland sliced by historical injustice. This injustice began with colonial treaties like Wuchale in 1889, which carved Ethiopia’s future without its consent. Long before independence flags fluttered over Asmara, the Afar roamed freely between highlands, salt plains, and the Red Sea coast from the Gulf of Zula to the port of Assab. The Afar are a proud Cushitic people: fierce, devout, and ancient. For centuries, the Afar were maritime nomads traders, warriors, and custodians of one of the Horn of Africa’s most strategic shorelines. But colonialism is a cartographer of violence, and Ethiopia still bleeds from the wound.

Today, Ethiopia is landlocked, and Assab has become a military zone. The Afar proud Ethiopians and ancient custodians of the coast remain divided, displaced, and politically erased. According to Human Rights Watch (2019), Afar communities in Eritrea’s Southern Red Sea Zone have faced systematic repression, restricted movement, and cultural erasure under the Eritrean regime. The coast that once connected Ethiopia to the world became a colonial beachhead first for Italy, then for Eritrea, and now for foreign military bases. Assab in Eritrea became a symbol of independence, but Assab was Ethiopia’s link to the world, and, especially for the Afar, it was homeland and memory. Assab: Ethiopia’s lost limb, was never foreign land it was Afars land, and the Afars are Ethiopians.

In Eritrea today, Afar voices are silenced, as Amnesty International has documented. The once-proud port of Assab is a shadow of its past patrolled by soldiers, leased to foreign forces, and closed to the people whose ancestors lived off its shores. The Eritrean regime does not celebrate Afar heritage; it controls it. There is no room for local autonomy or an Afar political party. Afar opposition groups like the Red Sea Afar Democratic Organization (RSADO) have long campaigned for cultural autonomy and the right of return, but are labeled traitors by the government in Asmara. In Ethiopia, the Afar still has a homeland with its region and flag but in Eritrea, their existence is reduced to a number: counted, not heard. Their identity is buried beneath the suffocating nationalism of a one-party state that tolerates no ethnic assertion. Even in Djibouti, ruled by an Issa-dominated elite, the Afar are second-class citizens in their own country.

Now we Ethiopians have a question for the world about our geographical amputation: How can Ethiopia, a country that stood uncolonized in African history, remain colonized by geography? How can the African Union speak of integration and free trade when its most populous landlocked member is denied its natural port? Why does the world speak endlessly about Palestine’s coast, but not Ethiopia’s? Why does the Red Sea have space for foreign navies American, Chinese, and Emirati but none for Ethiopians? Our question is not about revanchism or revenge but about peace and justice. We lost our coast in the name of peace, and we ask for restoration in the same spirit. Ethiopia’s question is about historical justice, geostrategic necessity, and ethnic truth.

With the stroke of a pen and the silence of international powers, Ethiopia lost not just territory but its coast. Over 1,151 kilometers of shoreline from Massawa to Assab were lost in the name of peace through mechanisms like the 2000 Algiers peace deal and Eritrea’s 1993 secession, devoid of Ethiopian input. But ask the Afar people of Eritrea’s Southern Red Sea Zone: Did they vote for this? Did they choose to be cut off from their kin across the Mereb? Or were they, like Assab itself, simply absorbed first by colonialism, then by a new nationalism with no space for their identity? Right after Eritrea’s secession, Isaias Afwerki’s first strategy was to neutralize the Afar and displace them. This wasn’t an accident; it was strategy. A divided Afar nation meant a weaker Ethiopia and a coast kept out of Ethiopian hands.

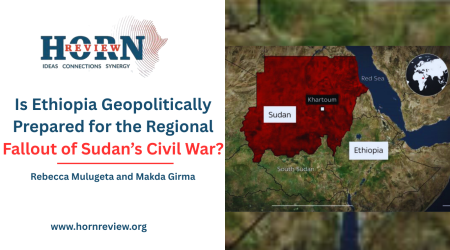

In the Horn of Africa, access to the Red Sea is everything. From colonial Italy to modern China, from UAE bases to U.S. counterterrorism missions, the Red Sea is a highway of power and the Ethiopian coast is its unacknowledged casualty. Even in peacetime, Eritrea has refused to negotiate port access, effectively weaponizing geography in violation of neighborly relations under the African Union Charter. While superpowers battle over ports and Djibouti cashes in on foreign bases, the people whose land made this game possible are excluded. The Red Sea is bought and sold, but never with the consent of either the Ethiopian Afar or the Eritrean Afar. The first people of the Red Sea coast now watch foreign powers sail it, wage war over it, and lease it without their say.

Today, Assab is a heavily militarized zone controlled by the Eritrean government and leased to foreign powers like the UAE. The salt-scarred port is now a logistical hub for wars in Yemen, but Ethiopian Afar voices are nowhere to be heard at the international level. Africa speaks of Pan-Africanism and Indigenous rights, yet Ethiopia’s predicament is normalized. The AU, IGAD, and the so-called Horn of Africa peace architecture all exclude Ethiopia’s rights. Ethiopia, with its 130 million people, remains boxed in, a continental giant without a coastline because the world forgot, or chose to ignore, that Assab was Ethiopian before it was ever Eritrean.

From an Ethiopian vantage point, the parallels between Israel’s maritime chokehold on Gaza and Eritrea’s denial of Red Sea access to Ethiopia are stark: both illustrate how coastal power can strangle a landlocked neighbor’s lifeline. Just as Palestinians have been prohibited from utilizing the Dead Sea’s fisheries and trade routes by blockade and restricted jurisdiction, Ethiopians have been deprived of their legitimate Red Sea outlet for the past three decades, forcing Ethiopia to rely on distant ports.

While Palestinians were denied their natural sea access from the Dead Sea, Ethiopians were denied theirs from the Red Sea. Both peoples, scarred by borders and blockades, have been cut off from the wealth of their seas. Eritrea defends its embargo as a sovereign security measure citing past hostilities and fears of proxy insurgencies just as Israel invokes self-defense to justify Gaza’s naval interdiction.

Under international humanitarian law, blockading powers must permit humanitarian relief and cannot wield port closures as collective punishment a principle Ethiopia echoes in its appeals to the African Union and the UN. Crucially, Ethiopia needs sovereign Red Sea access far more than alternative corridors because its economy bleeds billions annually in port fees, and its sovereignty remains hostage to foreign routes.

Ethiopia’s appeal to “remedial secession” and the notion of a “historical error” in Eritrea’s secession could, in theory, mirror Russia’s annexation of Crimea however, Ethiopia’s claim is pursued through diplomatic, legal, and informational means rather than tanks and paratroopers. Russia justified its actions by citing the need to protect Russian speakers and its deep historical ties to the region; similarly, Ethiopia’s historical ties and the imperative to safeguard the rights of Afar-speaking communities can justify a “corrective” return of these territories through a political remedy. Ultimately, the political symmetry is striking in Ethiopia’s case: secessionary theory cuts both ways, but the same as Russia Ethiopia’s claim must be seen equally under international law and diplomatic convention.

Justifications for Crimea’s transfer to the Ukrainian SSR in 1954 as a “historical error” echo Asseb’s transfer to Eritrea in 1993. Russian scholars invoked “remedial secession,” arguing that threats to Crimeans justified separation from Ukraine. Ethiopian scholars can invoke the same concept and could frame a UN-mediated referendum for Afar-majority districts as a corrective remedy arguing that, like Crimea’s ethnic Russians, Afar communities around Assab remain under threat from an authoritarian regime in Asmara. Ethiopia can publicly argue that successive colonial handovers from imperial decree to Italian and British trusteeship, and finally to the EPLF under the EPRDF constitute a profound historical miscalculation, akin to Khrushchev’s transfer of Crimea.

Ethiopian Afar lost their sea before Gaza, before Crimea, and the world has not yet spoken their name. This is not a call for war. It is a call for historical recognition and national repair. Peace between Ethiopia and Eritrea should not be based on “closed-door accords”; it must start with the truth: The Afar coast was Ethiopian, is Ethiopian and must be Ethiopian again. Asseb must be recognized internationally under Ethiopia’s sovereignty for a fair and lasting peace.

Ethiopia cannot remain landlocked forever; it is neither natural nor sustainable.”

By Surafel Tesfaye, Researcher,Horn Review