14

Jun

Guelleh’s Hardline Rhetoric: Djibouti’s Defiance on Ethiopia’s Sovereign Sea Access

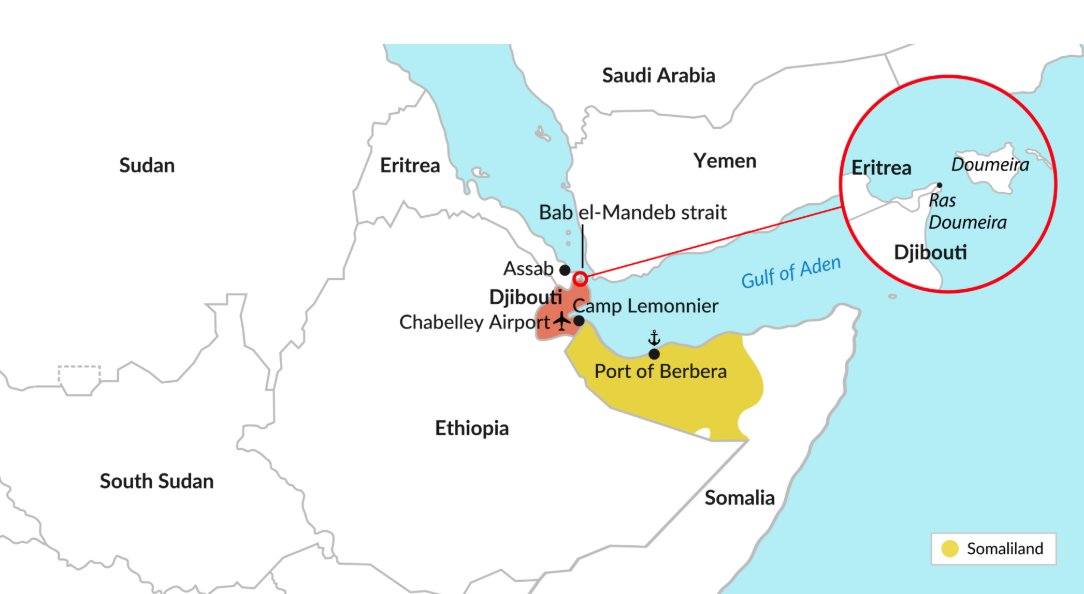

Since Eritrea’s secession in 1993, Ethiopia has endured the geopolitical challenge of becoming a landlocked country, severed from direct access to the Red Sea. Consequently, Addis Ababa has relied overwhelmingly on neighboring ports – most notably Djibouti’s, which facilitates over 90% of Ethiopia’s foreign trade. This structural dependency has naturally galvanized Ethiopia’s enduring pursuit of diversified and secure sovereign sea access, an imperative that transcends transient political agendas to embody a generational strategic necessity shaped by centuries of historical experience alongside pressing economic and security imperatives.

The absence of a maritime harbor is widely regarded as a formidable impediment to Ethiopia’s aspiration to reclaim its rightful place within Africa’s geopolitical and economic spheres and on the broader global stage. The pursuit of sovereign maritime access is thus not merely a government initiative but a deeply entrenched national concern. The loss of coastline following Eritrea’s independence and the contemporary international response – or lack thereof – toward Ethiopia’s status as a landlocked nation has been broadly perceived as inequitable. Ethiopia’s quest is both legitimate and justifiable, driven by the needs of its vast population and an economy reliant on stable and sustainable access to international trade corridors.

Against this backdrop, Ethiopia has proactively sought to expand its maritime gateways beyond Djibouti, exemplified most notably by the January 2024 Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Somaliland to develop the Berbera port. In response, Djibouti’s subsequent offer of maritime access to Port Tadjourah has been widely interpreted as largely symbolic, lacking substantive commitment to alleviating Addis Ababa’s logistical and strategic concerns. This juxtaposition of a concrete Ethiopian initiative with a largely performative Djiboutian response has only served to exacerbate bilateral tensions, prompting vociferous opposition and outright rejection from Djibouti’s leadership.

Djiboutian President Ismaïl Omar Guelleh’s recent public statements, in which he equated Ethiopia’s maritime initiatives to acts of territorial encroachment, epitomize a defensive posture that prioritizes exclusion and sovereignty in a manner that precludes constructive regional collaboration. This hardline rhetoric starkly contradicts the realities of regional interdependence and economic symbiosis that define the Djibouti-Ethiopia relationship.

Compounding this contradiction is Djibouti’s simultaneous rejection of Ethiopia’s naval base requests alongside its hosting of numerous foreign military installations from global powers including the United States, China, France, Japan, Italy, Saudi Arabia, and the United Kingdom. These foreign bases yield hundreds of millions of dollars annually in rents, conferring economic stability and diplomatic leverage that far exceed Djibouti’s demographic and geographic scale. The selective denial of Ethiopia’s far more modest and regionally vital requests underscores a nuanced and politically expedient interpretation of sovereignty – one that appears to privilege the interests and preferences of external actors over equitable, regionally grounded partnerships.

This irony is further heightened considering Ethiopia’s pivotal contribution to Djibouti’s economy, accounting for approximately 95% of the port traffic through the Ethio-Djibouti corridor, which serves as the principal trading artery for the entire Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) region. While this symbiotic economic relationship generates substantial revenue for Djibouti, the country remains reliant on Ethiopia for critical resources such as water and electricity – testament to a profound mutual interdependence. Yet, Djibouti’s leadership persistently dismisses Ethiopia’s proposals for sovereign corridors and naval facilities, framing them as existential threats rather than opportunities for cooperative development. This stance diverges sharply from established international precedents, where neighboring states have navigated complex maritime access arrangements through mature diplomacy and mutual accommodation, avoiding analogies that misconstrue rights as aggression.

President Guelleh’s oft-repeated assertion that “Djibouti is not Crimea” is a disingenuous and misleading comparison. Ethiopia’s pursuit is one of peaceful, legitimate sovereign access to the sea from a long-standing neighbor – an inalienable right for a nation of Ethiopia’s size, historical stature, and economic weight. Djibouti’s selective sovereignty narrative elevates short-term economic gains derived from foreign military presence above the strategic necessities and regional stability benefits that Ethiopia’s aspirations could bring. This interpretation not only exaggerates the threat posed by Ethiopia’s legitimate ambitions but also undermines Djibouti’s own foreign policy commitments to neutrality and regional cooperation.

Moreover, Ethiopia’s proposal for a sovereign corridor linking its border to Tadjourah port represents a practical, forward-looking solution to enduring logistical challenges, one that promises significant mutual benefit. President Guelleh’s categorical rejection of this initiative, despite the potential for enhanced trade efficiency, cost reduction, and shared prosperity, remains perplexing. Comparative regional models – such as Morocco’s generous approach to maritime access for neighboring states – demonstrate that strategic leadership is better consolidated through openness and cooperation rather than suspicion and exclusion. Yet, Djibouti’s administration continues to treat Ethiopia’s proposal as a zero-sum threat, rather than an opportunity to anchor Addis Ababa’s rising influence constructively within Djibouti’s long-term geo-economic framework.

Complicating this landscape further is Egypt’s recent strategic maneuvering in Djibouti, which introduces an additional layer of complexity and competition. The November 2024 Egypt-Djibouti MoU, which establishes Egyptian logistics zones within Djibouti and integrates port infrastructure linkages between the two countries, fundamentally alters regional dynamics in a manner that directly challenges Ethiopian interests. Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s April 2025 visit to Djibouti, during which both leaders underscored that Red Sea security should be led exclusively by littoral states, signals an intensification of this partnership. These developments compel urgent reflection on their underlying intentions and far-reaching implications.

Foremost among these concerns is the context of escalating Ethiopia-Egypt tensions over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) and Egypt’s broader regional ambitions. From the Ethiopian perspective, Djibouti’s rejection of Ethiopia’s maritime requests amid this backdrop may be interpreted as politically motivated and manipulatively timed. Moreover, the question arises: what are the implications of Djibouti granting Egypt expanded port access and infrastructure linkages, while simultaneously denying Ethiopia’s peaceful and pragmatic corridor initiative and sovereign maritime access?

Djibouti’s persistent opposition to the Ethiopia-Somaliland MoU further highlights a broader pattern of skepticism and resistance that calls into question Djibouti’s strategic intentions and its willingness to accommodate Ethiopia’s legitimate aspirations. Nevertheless, Ethiopia’s approach to securing maritime access has been consistently anchored in peaceful diplomacy, mutual respect, and a commitment to regional cooperation.

In light of these complex dynamics, it is incumbent upon Djibouti to undertake a comprehensive strategic policy review that reorients its priorities toward regional integration and shared prosperity rather than narrow short-term gains. This process should begin with a candid self-assessment of how its current posture conflicts with its own stated foreign policy principles. Moreover, Djibouti is uniquely positioned as a military and logistical hub to serve as a broker for broader Horn of Africa security collaborations, rather than selectively aligning with external powers in ways that risk undermining regional stability.

By Yonas Yizezew,Researcher,Horn Review