6

Nov

Foreign Military Presence and Eritrea’s Calculus in the Red Sea

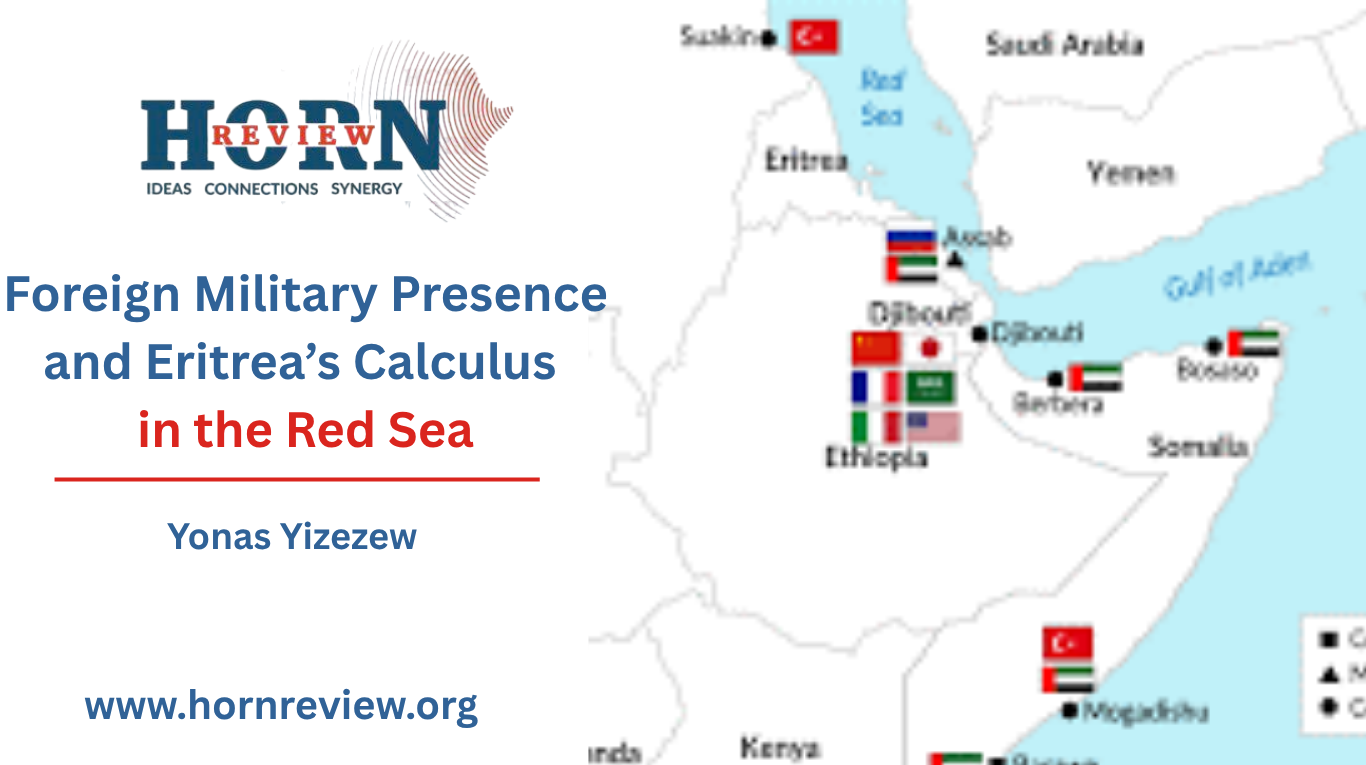

The Red Sea and the Horn of Africa occupy one of the world’s most strategic maritime corridors. For centuries, powers from within and beyond the region have sought to influence its sea lanes, ports, and coastal states. In the modern era, this contest has taken a new shape, the proliferation of foreign military bases. The United States, France, China, and several Gulf and Middle Eastern states maintain facilities or access arrangements across the littoral, often justifying them as necessary for countering piracy, terrorism, and ensuring freedom of navigation. While these arguments have some merit, such presences also carry deeper political and strategic motivations. They serve as platforms for projecting influence, securing trade routes, and shaping regional alignments, sometimes producing the very insecurities they claim to mitigate.

It is within this complex environment that President Isaias Afwerki of Eritrea recently delivered a pointed critique. Speaking to Egyptian TV Channel, he described foreign military bases in the Red Sea as sources of instability and argued that the region’s peace and security should be managed by the countries themselves. He insisted that Eritrea rejects the establishment of any foreign bases on its soil, portraying such arrangements as instruments of dependency and as threats to national sovereignty. His reasoning aligns with a widely shared sentiment in Africa and the Global South that external military presence often undermines local agency and regional ownership of security affairs.

In principle, this position is logically consistent and resonates with a broader call for autonomy and collective self-reliance among regional states. However, Eritrea’s historical and contemporary record presents a more complex picture. The country’s engagements over the years reflect a pragmatic approach to foreign partnerships, one guided less by ideological consistency than by strategic necessity. While publicly rejecting external bases, Eritrea has, at different moments, entered into security and logistical arrangements that effectively granted access to foreign actors when this served its immediate interests.

The most prominent example is Eritrea’s relationship with the United Arab Emirates. Between 2015 and 2021, the UAE established a significant military and logistical presence at Assab Port, which became a key operational hub for its involvement in the Yemen conflict. Satellite imagery and independent investigations documented major expansions of infrastructure, including airstrips, hangars, and supply facilities. This arrangement provided Eritrea with economic and diplomatic benefits, while positioning Assab as a vital node in a wider Gulf-led military campaign. During this period, the Eritrean government did not frame the UAE’s presence as a violation of sovereignty or as an imported problem. Rather, it was viewed as a strategic partnership. Only after the UAE scaled down its Yemen operations and began withdrawing from Assab did the official rhetoric shift, portraying foreign bases as inherently destabilizing.

This episode demonstrates a form of strategic selectivity that characterizes Eritrea’s foreign policy posture. When external engagement aligns with national or regime interests, the principle of non-alignment tends to be interpreted broadly. When those interests shift, the rhetoric of sovereignty and regional autonomy is reasserted as a diplomatic shield. It also place the government’s categorical rejection of foreign bases in a more nuanced light.

Earlier precedents further reinforce this pattern. In the late 2000s, multiple United Nations Monitoring Group reports indicated that Eritrea had maintained security and logistical ties with Iran, including possible use of its ports for maritime shipments. These reports, while politically sensitive and at times disputed, nonetheless reflected Eritrea’s willingness to engage powerful external actors under specific conditions. Such relationships positioned Eritrea within the complex web of Middle Eastern rivalries, contradicting its later insistence that external involvement in regional waters is inherently harmful.

More recently, Eritrea’s diplomatic posture regarding the Red Sea has again demonstrated this orientation. Amid the renewed debate over Ethiopia’s demand for sea access, Asmara has reportedly deepened its outreach to Saudi Arabia, offering preferential access to the Assab port area. Though framed as an economic initiative, such an offer carries clear strategic undertones. By inviting a powerful regional actor into its maritime domain, Eritrea appears driven by persistent suspicion and insecure posture, using external partnerships to compensate for its own isolation and mistrust within the region. This logic contrasts sharply with President Isaias’s public warnings that external involvement in the Red Sea undermines local peace.

It is therefore possible to interpret Eritrea’s position not as a rejection of all foreign military engagement, but rather as a selective opposition one shaped by context, leverage, and timing. The government’s stance tends to harden when external bases belong to actors outside its immediate orbit or from within the region. Conversely, when partnerships promise tangible returns or political support, the rhetoric of sovereignty becomes more accommodating.

This duality, however, risks undermining the credibility of President Isaias’s stated concern about the militarization of the Red Sea, highlighting the gap between principled rhetoric and selective, self-serving practice. The issue he raises that foreign bases can generate instability remains empirically supported by decades of regional experience. However, Eritrea’s own conduct reveals that its application of this principle is situational rather than absolute. Its foreign policy, in practice, operates within a framework of transactional realism rather than ideological purity.

From a regional perspective, this posture carries significant costs. It amplifies mistrust among neighboring states, fosters uncertainty over Eritrea’s intentions, and risks entangling the country in broader geopolitical rivalries as it seeks to leverage its strategic location. It also undermines the credibility of its advocacy for regional self-reliance. When a state publicly condemns the very practice it has previously embraced, its message risks being viewed as opportunistic. Moreover, such inconsistencies weaken efforts to develop a coherent Red Sea security framework, as mutual suspicion among regional states deepens.

If Asmara genuinely seeks to promote a region free from destabilizing foreign bases, it could take practical steps to reinforce its credibility. Making the terms of any port or military access agreements public, engaging constructively within regional institutions and countries, and committing to the demilitarization of maritime partnerships would all strengthen its position. Equally important would be sustained cooperation and confidence-building with neighboring states particularly Ethiopia, Sudan, and Djibouti to develop a collective security framework rooted in transparency and mutual trust. Such measures would convert a sound principle into tangible policy and demonstrate that Eritrea’s opposition to foreign bases is guided by consistency, regional responsibility, and a shared vision for stability rather than circumstance.

By Yonas Yizezew, Researcher, Horn Review