29

Oct

Ethiopia’s Water Diplomacy: A Pursuit of Equitable Institutions and Regional Stability

Introduction

Water scarcity, exacerbated by climate change, population growth, and urbanization, positions water as a potential conflict trigger in the Horn of Africa. Ethiopia stands at the core of these hydrological challenges, contributing substantially to transboundary flows while contending with historical exclusions from governance structures. Disputes over the Nile River and Red Sea access arise primarily from outdated colonial institutions favoring downstream and coastal states, rather than from scarcity alone.

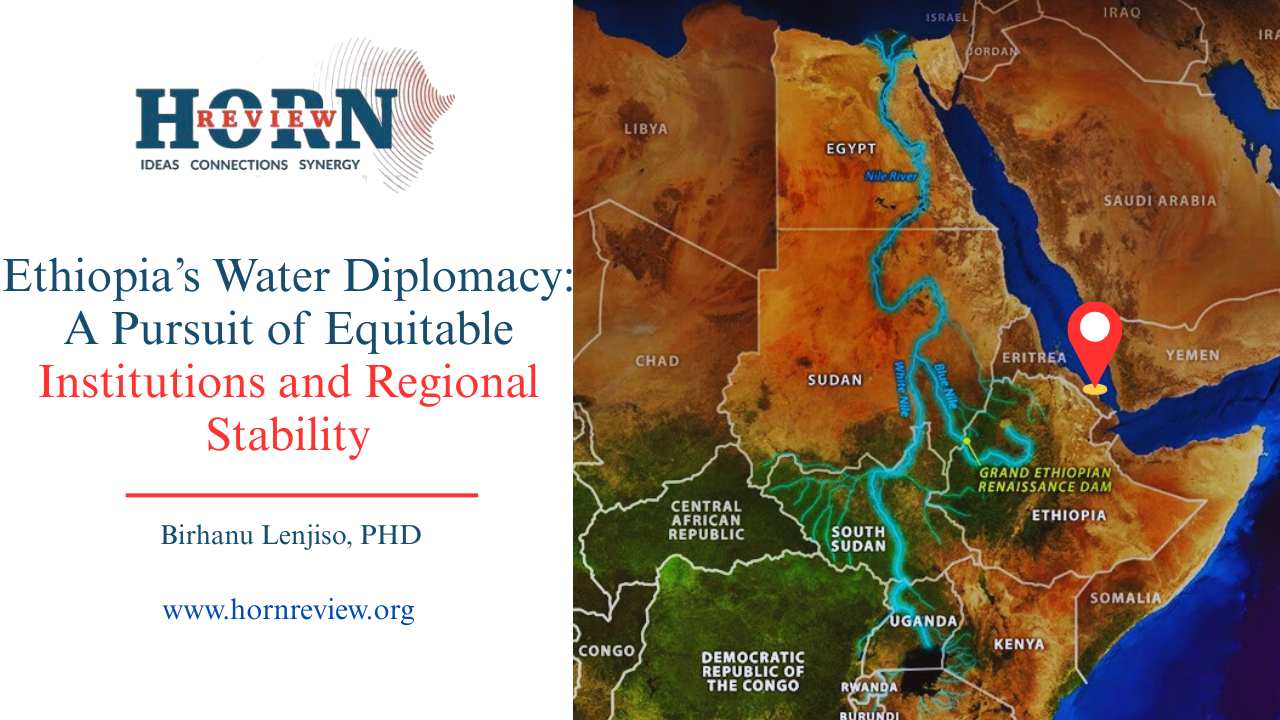

Ethiopia, the water tower of Africa, is the source of major rivers that sustain its population as well as neighboring counties. The Blue Nile (Abbay) supplies about 85% of the Nile’s flow, underscoring Ethiopia’s role in the riparian country’s ecosystem. Yet, it receives no formal allocation under the colonial treaties, effectively exporting water without compensation. Tension over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) emanates from those outdated colonial arrangements, with Egypt and Sudan expressing concerns over potential flow reductions despite Ethiopia’s claims of limited impact. Ethiopia’s quest for Red Sea access adds a layer to this colony-induced water strain.

Disputes over the Nile and Red Sea, Ethiopia’s dual waters of destiny, reflect institutional betrayals rooted in colonial legacies. These colonial institutions are designed to privilege downstream and coastal countries while redistricting Ethiopia’s equitable water use and maritime pathways. This article, therefore posits that Horn water conflicts stem from institutional failures and advocates multidisciplinary diplomacy as a remedy. It urges Ethiopia to cultivate water-savvy diplomats to harness its resources, transitioning regional relations from competition over water resources to collaboration through water resources.

Conceptual Framework: Understanding Water Conflict

Water conflict encompasses disputes concerning access, control, or utilization of water resources, intertwined with geopolitical, economic, and environmental dimensions. These occur intra- or interstate, propelled by scarcity, pollution, or inequitable distribution. Scholars categorize them as hydrospheric (direct competition), economic (infrastructure clashes), and political (sovereignty proxies). Primary drivers include low precipitation, demographic pressures, and basin interdependencies, which can escalate to armed confrontations, if unresolved.

In the Horn of Africa, water conflicts reflect global trends but are shaped by colonial legacies and secessionist histories. These tensions manifest as resource-driven inequities, where upstream developments threaten downstream water supplies, and as post-secession challenges, leaving landlocked nations deprived of maritime access. Ethiopia’s experience illustrates these dynamics uniquely. Typically, downstream countries suffer from rules imposed by upstream nations, but Ethiopia, an upstream country, is constrained by colonial agreements favoring downstream states. Similarly, while new nations may prioritize sovereignty over maritime access, Ethiopia, a sovereign state, unfairly lost its maritime access to a seceded region.

The Nile Basin, spanning 11 countries and supporting over 300 million, suffers from colonial treaties that allocated shares to Egypt and Sudan, disregarding Ethiopia’s 85% input. The 1929 Anglo-Egyptian Treaty awarded Egypt “historical rights” and veto authority over upstream projects, distributing 48 billion cubic meters (bcm) annually to Egypt and 4 bcm to Sudan. The 1959 Nile Waters Agreement between Egypt and Sudan expanded this to 55.5 bcm for Egypt and 18.5 bcm for Sudan, marginalizing upstream riparians including Ethiopia despite 85% contribution to the flow. These pacts entrenched “hydro-hegemony,” constraining Ethiopia’s progress and resource optimization. Ethiopia repudiates them, invoking non-consent under Article 34 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties.

Ethiopia’s maritime challenges originated in the late 19th century. Once a Red Sea power, it lost ports like Assab and Massawa to Italian colonization in 1889. Post-World War II, a 1952 UN federation with Eritrea reinstated access, but Eritrea’s 1962 annexation ignited a 30-year independence struggle, culminating in 1993 secession and Ethiopia’s landlocking. A 1993 accord assured duty-free Assab access, but the 1998–2000 border war sealed ports, compelling reliance on Djibouti that cost Ethiopia billions in fees.

In both domains, ample resources turn contentious due to asymmetrical institutions lacking fairness. Analyses like Halidu et al. (2025) attribute GERD frictions to those outdated exclusionary arrangements, contravening the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention’s equitable utilization tenet. The IPCC (2022) notes how rigid institutions magnify climate-driven scarcity, fostering economic and security dilemmas. Current hotspots, including stalled GERD negotiations and Ethiopia’s maritime pursuits, highlight these impasses, worsened by demographic and urban pressures. Adaptive structures like the Nile Basin Cooperative Framework Agreement (CFA) are essential to avert “water wars” and unlock gains, such as GERD’s annual 0.035 km³ silt reduction in Sudan’s Roseires Reservoir.

Water Diplomacy as a Neutralizer: The Promise of Multidisciplinary Approaches

Water diplomacy merges foreign policy, negotiation, and technical know-how to collaboratively govern shared waters, converting disputes into peace prospects. It incorporates preventive (early warnings), integrative (benefit-sharing), cooperative (joint bodies), and technical (data sharing) components, viewing water as an adaptable resource for reciprocal advantages. Outcomes include trust enhancement, economic growth via hydropower trade, and regional cohesion tackling migration and food insecurity. In the Horn, it could reposition the Nile as a communal resource and secure balanced maritime access without compromising sovereignty.

Ethiopia’s approach emphasizes “fair and reasonable utilization” per international norms. For the Nile, it advances the 2010 CFA, ratified by six upstream nations and effective in 2024, through the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI) to supersede colonial pacts. The GERD illustrates this: a non-consumptive initiative releasing 99% of flows, Ethiopia proposes electricity exports as enticements, though 2023 trilateral discussions faltered over drought measures.

On the Red Sea, Ethiopia pursues formalized access sans territorial claims. The 2018 Eritrea peace accord reopened dialogue, while the 2024 Somaliland MoU provides Berbera port equity, diversifying routes and trimming dependency expenses. Citing UNCLOS Article 125 on landlocked states’ transit entitlements, Ethiopia fosters “win-win” arrangements to bolster trade and stability.

The Way Forward: Transforming Conflict into Cooperation for Stability and Prosperity

Addressing Horn water disputes demands a comprehensive strategy. For instance, reviving GERD talks under African Union auspices and employing independent hydrological simulations can cultivate trust. Ethiopia should operationalize the CFA fully, with Egypt and Sudan funding upstream resilience efforts. For maritime access, it is critical to emphasize bilateral engagements to reinstate for instance the 1993 Assab pact with arbitration provisions, alongside diversification through Somaliland and Kenya’s Lamu Port.

Wider reforms entail reinforcing the NBI with enforceable dispute resolution and shared infrastructure, like basin-wide alert systems. Civil society and Track II exchanges can temper nationalism, complemented by international climate funding to spur collaboration. Such measures could yield prosperity, including 10–15% GDP growth from hydropower and irrigation, as per ISS African Futures (2023).

Ethiopia’s abundant water resources offer immense diplomatic leverage, yet the country faces a paradox: its diplomats often lack the interdisciplinary expertise to wield this asset strategically. To position Ethiopia as East Africa’s water nexus, training programs, inspired by IHE Delft and enriched with domestic insights, must prioritize holistic hydrological, regional, and historical acumen. While Ethiopia’s water wealth fuels ambitions for energy sales and leadership in revising CFA-driven treaties, its envoys struggle to synthesize these into a cohesive diplomatic strategy. Maritime specialists need deep awareness of Ethiopia’s historical loss of sea access to strengthen negotiations. By advocating “benefit-sharing,” such as Sudanese flood mitigation (Whittington et al., 2014), and aligning with SIWI frameworks, Ethiopia can transform its water abundance into a tool for regional cooperation, repositioning itself as a pivotal ally.

Conclusion

Ethiopia’s water conflicts, originating from institutional lapses like the 1929/1959 treaties and Eritrea’s 1993 secession, imperil a region burdened by climate and population stresses. Reframing them as equity and governance shortcomings enables Ethiopia to reclaim its “Water Tower” status through multidisciplinary diplomacy. Proactive initiatives promote justice, adjusting colonial disparities for accord. Ongoing multilateralism converts waters from strife origins to mutual prosperity channels. Specialized diplomat training will amplify Ethiopia’s regional influence. The decision is critical: diplomacy yields collaboration, stability, and abundance; neglect invites escalation.

This reframing empowers Ethiopia to assert its pivotal position, supplying 85% of the Nile’s flow while pushing for equitable benefits. The GERD embodies a non-consumptive hydropower endeavor that discharges nearly all inflows, curbing silt in Sudan’s Reservoir and facilitating electricity exports for shared growth. Likewise, the 2024 Somaliland MoU for Berbera access aims to broaden trade paths and leverage UNCLOS rights for landlocked countries, alleviating Djibouti dependency vulnerabilities. The CFA’s activation advances inclusive governance, despite Egypt and Sudan’s opposition.

In general, multidisciplinary water diplomacy, blending foreign policy, technical proficiency, and preventive strategies, provides a means to defuse these tensions, evolving flashpoints into cooperative avenues. Ethiopia’s forward actions, including CFA advocacy and non-aggressive “win-win” maritime deals, champion equity and realign colonial legacies for unity. This can shift shared waters from contention vectors to collective prosperity pathways. Equipping diplomats with hydrological expertise, historical perspective, and negotiation prowess will position Ethiopia as East Africa’s strategic center. The urgency is evident: unaddressed institutional gaps risk escalation whereas effective diplomacy cultivates lasting cooperation, stability, and communal wealth, reshaping the Horn’s trajectory for future generations.

By Birhanu Lenjiso, PHD

References

Halidu, A., Joy, N. I., & Onochie, O. S. (2025). From colonial agreements to contemporary conflict: the Nile Waters Treaties and the Egypt-Ethiopia GERD Crisis. British Journal of Interdisciplinary Research, 2(7), 1–23.

Institute for Security Studies. (2023). African Futures: Long-term trend analysis. Pretoria: ISS.

IPCC. (2022). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report.

Stockholm International Water Institute. (2018). The Multi-track Water Diplomacy Framework: A guide for designing context-specific processes. https://siwi.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/thigj_the-multi-track-water-diplomacy-framework_webversion-1-1.pdf

Swain, A. (1997). Ethiopia, Sudan, and Egypt: The Nile River Dispute. Journal of Modern African Studies, 35(4), 675–694.

Whittington, D., Waterbury, J., & Jeuland, M. (2014). The Grand Renaissance Dam and prospects for cooperation on the Eastern Nile. Water Policy, 16(4), 595–608.

Whittington, D., et al. (2022). The long shadow of the 1959 Nile Waters Agreement. Water Policy, 26(9), 859–878.