11

Oct

How Vulnerability at Chokepoints Shapes Great Power Politics and Why Ethiopia Can’t Afford To Lag

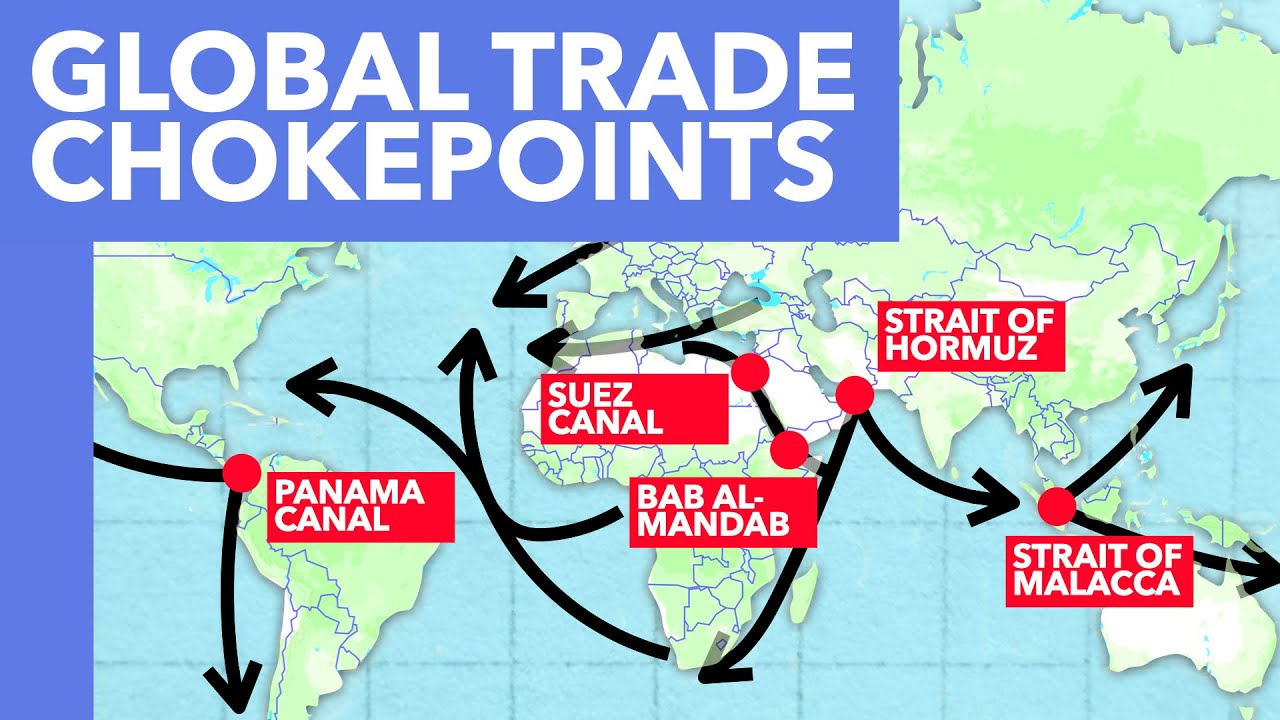

In an era of globalized supply chains, the world’s most critical maritime corridors are not just arteries of commerce but also central fronts in a new age of strategic competition. Modern states prize satellites, cyber tools and long-range strike, yet day-to-day commerce, energy flows and naval logistics still run through a handful of narrow maritime throats. When those throats are pinched, the effects would be rise of freight costs, stalling of supply chains, mounting political pressure and even great powers find their options constrained. The contemporary contest over those passages is not limited to ships and sailors. It folds together asymmetric violence, legal regimes, sanction-evasion, climate stress and high-stakes competition for alternative routes.

The Suez Canal and Bab el-Mandeb

Suez and Bab el-Mandeb remain Europe’s shortest lifeline to Asia. The canal is a narrow human achievement that moved huge volumes of trade and, until recently, carried a steady, predictable flow of ships between the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean via the Red Sea. When a single containership blocked the canal in 2021, the episode revealed how brittle that predictability could be. The Ever Given standoff became shorthand for the catastrophic ripple effects a local incident can generate in global logistics. The Red Sea adjacent to the Suez gateway has since evolved into a security corridor. From late 2023 the Houthi campaign in Yemen widened from symbolic strikes to sustained attacks on merchant tonnage, deploying missiles, drones and small boats against vessels transiting to and from Suez. The cumulative result has been a repeated contraction of commercial traffic through the canal and large-scale rerouting through the Cape of Good Hope with immediate costs for voyage time, bunker consumption and port congestion. International navies and ad hoc convoys have responded to deter or intercept attacks, but the naval presence has not erased the economic penalty of ships taking the long route. The Suez/Bab el-Mandeb episode shows how asymmetric actors, operating at low cost, can transmit pain to distant capitals by attacking the narrow nodes that power globalization.

The Strait of Hormuz

Further east, the Strait of Hormuz represents a chokepoint of an even more fundamental nature in energy supply. Roughly one fifth of global liquid petroleum moves past that tight corridor at the mouth of the Persian Gulf. The physical geography of the strait is short, shallow and bordered by states that possess the capacity to close the strait. During the Israel-Iran confrontation, Iran’s warnings to potentially close the Strait of Hormuz demonstrated the strait’s critical role and triggered fears of disruption across global energy markets. That leverage has a profound multiplier effect. Energy markets react instantaneously to perceived threats in Hormuz. Major importers in Asia and buyers in Europe face price and supply risks that cascade quickly through industry and public budgets. States hedge by stockpiling, by seeking pipeline or overland links where possible, and by sustaining naval escorts to keep transit open. However, the physical chokepoint remains a single-point vulnerability for the global energy system.

The Strait of Malacca

The Strait of Malacca is Asia’s economic narrow waist and the source of a persistent strategic anxiety for Beijing. An enormous share of China’s seaborne trade and most of its oil imports pass through the strait that narrows between Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula. For decades Chinese strategists have invoked the “Malacca dilemma”: in a major confrontation, control of or denial from that passage could inflict crippling economic pain. The response has been predictable: Beijing has pursued a three-track strategy. First, it has built dual-use port infrastructure and invested heavily in overseas terminals and logistics corridors across South Asia and East Africa. Gwadar in Pakistan and Kyaukpyu in Myanmar exemplify projects intended to shorten or bypass the Malacca route. Second, Beijing has struck energy deals and developed pipelines to reduce sole dependence on ocean transit. Third, China has steadily expanded maritime capabilities, escorts for shipping, overseas logistics and a modest network of bases to protect sea lines of communication. Those moves increase resilience but do not remove vulnerability. Overland alternatives are politically fragile and port investments do not instantly replace the throughput lost if the strait were contested. The Malacca dilemma is therefore not a problem with one simple solution, instead, it is a constant factor shaping China’s strategy both at sea and on land.

The Black Sea Gateway: The Turkish Straits

The Turkish Straits of the Bosporus and the Dardanelles are a reminder that legal bargains can be as decisive as force. The Montreux Convention of 1936 assigns Turkey decisive authority over naval passage between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. That legal architecture acquired fresh potency after the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Turkey controls the only easy way for Russia’s Black Sea fleet to leave the sea, giving it power not just over Russian naval movements but also over the passage of allied ships into the Black Sea. The war has shown how a well-timed invocation of rules, plus pragmatic diplomacy, can control access more effectively than naval standoffs. Turkey has used that leverage to mediate commercial grain corridors and to shape proposals for safe passage, while insisting on its strategic autonomy. The Montreux regime illustrates the point that chokepoints are not merely geographic features; they sit inside legal and diplomatic frameworks that can amplify small states’ influence over larger rivals.

The Panama Canal

The Panama Canal sits across the hemisphere as the strategic complement to Suez. For the United States, reliable access to the Canal is a practical requirement for rapid redeployment between oceans, for commerce and for military logistics. In recent years Washington has stepped up exercises with Panama and concluded security cooperation arrangements designed to reassure access in crisis. That activity has three roots. The first is immediate: the Canal is vulnerable to climate shocks that have already reduced daily transits during drought episodes. The second is strategic: rising Chinese economic involvement in Latin American ports and recent negotiations over port ownership near the Canal have prompted Washington to reassert partnership. The third is political: any hint that large parts of transshipment infrastructure might fall under adversarial influence generates pressure in Washington to respond. The result is an overt U.S. attempt to combine presence and partnership in the Canal’s near-term security architecture. This posture reassures U.S. logistics, but it also sharpens great-power competition in the Western Hemisphere.

Taken together, these sites form a network of strategic stressors whose logic now repeats. First, hybrid coercion. Actors short of open conflict prefer deniable disruption. The Houthis’ campaign in the Red Sea and Iran’s maritime leverage in Hormuz show that asymmetric tactics can impose global costs cheaply. Shadow fleets and covert ship-to-ship transfers represent a financial analogue to that hybrid playbook: they avoid direct state confrontation while preserving critical revenue streams. Second, legal and policing instruments are potent. Montreux’s legal framework, Suez and Panama’s authorities, each demonstrate the leverage embedded in rules and enforcement. Third, climate and infrastructure fragility are now operational variables. Drought and silt, from Panama’s reservoirs to reduced Suez transits, raise the frequency and severity of non-kinetic shocks. Fourth, great powers hedge by building redundancy. China’s ports, pipelines and overland corridors aim to reduce dependence on single sea lanes; the U.S. sustains forward naval presence and builds partner capacity; Russia opts, opaque shipping practices, Arctic and pipeline routings such as Arctic LNG routes, and financial and diplomatic workarounds to preserve market access. These dynamics are visible in how each major actor has adapted to the chokepoint environment, while making them vulnerable, it forces them to find alternatives.

These patterns produce predictable policy tensions. The picture that emerges is not one of inevitable collapse, nor is it one of simple control. Chokepoints remain leverage points precisely since they are narrow and because the modern economy is finely tuned to low-friction trade. The same geometry that concentrates risk also concentrates opportunity. Small states that sit astride these passages can magnify their voice.

Whoever controls the choke, or who can credibly keep it open, holds a transaction cost the world cannot ignore. The twenty-first century will not be decided only by cloud computing and hypersonic missiles. It will also be decided in straits, canals and shallow seas where economies, law and force meet. Policymakers who ignore those narrow places do so at their peril.

The same logic that drives global powers to secure redundancy applies equally to emerging and regional powers that depend on external corridors for survival. The fear of suffocation shapes national strategy. Various powers strategize to reduce vulnerability and reclaim autonomy over critical lifelines.

Among these nations, Ethiopia faces a comparable dilemma. Despite its long history along the Red Sea and its cultural, political, and economic proximity to the maritime corridor, it remains landlocked, dependent on foreign ports for nearly all of its trade. This dependence has turned access to the sea into a structural suffocation on its sovereignty and economic resilience.

For Ethiopia, the Red Sea is not simply a geographic aspiration, it is a question of strategic survival. Its economy is growing, yet its logistical artery lies in the hands of others. In a region where maritime control increasingly defines political weight from Egypt’s Suez leverage to Djibouti’s port diplomacy, Ethiopia cannot remain indefinitely detached from the Red Sea’s strategic architecture. Securing a sovereign and sustainable access route to the sea would not only guarantee logistical autonomy but also position the country as a legitimate stakeholder in the evolving politics of the Red Sea basin. As one of Africa’s demographic and economic giants, Ethiopia’s participation in maritime affairs is not optional, it is essential to balance regional power and to ensure that the sea connecting three continents remains open, stable, and equitably governed, making Ethiopia a central stakeholder in Red Sea geopolitics.

By Yonas Yizezew, Researcher, Horn Review