8

Sep

The Strategic Rationale Behind The Ethiopia-Somaliland Maritime Agreement

The recent proclamations by the former President of Somaliland, Muse Bihi, aired through the Somal Chronicle interview, proffer a narrative that demands intellectual deconstruction. His characterization of Ethiopia as being overpowered and consequently checkmated by international coalitions constitutes an oversimplification, a reductionist fallacy that obfuscates the intricate and interwoven geopolitics in the Horn of Africa. This portrayal, which anoints Somalia as the victor, not only misrepresents the extant realities but also ignores the calibrated, strategic move underpinning Ethiopia’s enduring quest for maritime access. This treatise shows to mount a formidable defence of Ethiopia’s position, dissecting the specious claims through a multidisciplinary lens of international jurisprudence, political realism, and economic necessity, thereby reframing the Memorandum of Understanding not as a failure, but as a single, strategy in a much grander, long term design.

The assertion that Ethiopia succumbed to a monolithic front of international pressure betrays a fundamental misapprehension of the nation’s diplomatic ethos and its navigational prowess within the complex ways of multilateralism. To posit that entities like the African Union, the Arab League, and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation collectively overpowered Ethiopian diplomacy is to subscribe to a neo realist fantasy of international relations as a contest of raw power. This is a myopic view.

In contradistinction, Ethiopia’s engagement shows a far more a sophisticated form of reflexive diplomacy. Hosting the African Union headquarters for decades, Ethiopia is not an outsider reacting to pressure but a principal architect within the continental political edifice. Its decision to pursue the Ankara Declaration, a pact brokered under Turkish mediation that pledges further technical dialogue was not an act of capitulation. Rather, it was a strategic recalibration, a demonstration of diplomatic maturity that prioritizes long term regional stability and coalition building over the immediate, and potentially destabilizing, implementation of a single agreement. It represents a Hegelian synthesis, moving beyond the thesis of the MoU and the antithesis of international opposition towards a more sustainable, negotiated pathway.

A central pillar of the criticism levelled against Ethiopia is its alleged contravention of international law, specifically the sacrosanct principle of territorial integrity. This critique, however, crumbles under rigorous legal scrutiny and fails to engage with the interplay between de jure statutes and de facto political realities.

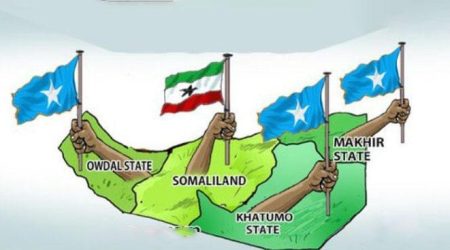

While Ethiopia is not a signatory to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea ,the instrument’s provisions regarding the rights of landlocked states are widely considered to reflect customary international law. This corpus juris grants landlocked nations a right of access to and from the sea, a right Ethiopia is legally and morally entitled to exercise. The MoU with Somaliland was a manifestation of this right, conceived as a mutual compact between two entities possessing the practical capacity to negotiate.The elephant in the room, of course, is Somaliland’s contested statehood. While Somalia’s claim to territorial sovereignty is recognized de jure, the irrefutable de facto reality is that Somaliland has operated as a separate, self-governing polity for three decades, replete with its own government, security apparatus, and a history of international partnerships. Engaging with Somaliland is not an act of irredentism but an acknowledgment of political facts on the ground a practice engaged in by numerous other nations, albeit often through quieter channels.

The subsequent Ankara Declaration itself implicitly affirms Ethiopia’s right to negotiate port access, shifting the venue of negotiation to Mogadishu and thereby demonstrating Ethiopia’s commitment to operating within a flexible, rather than rigid, legal framework.

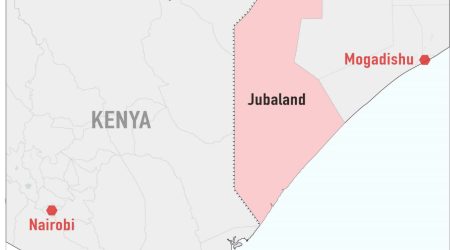

Egypt’s staunch support for Somalia is inextricably linked to the hydrological politics surrounding the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam and the perennial negotiations over Nile waters. For Cairo, opposing Ethiopia’s strategic moves is a consistent feature of its foreign policy, aimed at constraining Addis Ababa’s growing regional influence. Similarly, Turkey’s eager mediation is not born of pure altruism but is a strategic investment in its own sphere of influence, cemented by its significant military and economic place in Mogadishu. Thus, the international coalition against the MoU is not a monolith but a conglomeration of vested interests, each using the banner of Somali sovereignty to advance its own geopolitical objectives. Ethiopia’s engagement with Somaliland was a legitimate counter move within this complex and often duplicitous arena.

At its core, Ethiopia’s pursuit of the MoU was driven by an existential imperative ,a non-negotiable requirement for national economic security. With a population exceeding 120 million and an economy straining toward middle-income status, Ethiopia’s landlocked condition is its most profound strategic vulnerability. A staggering 95% of its trade transits through a single corridor Djibouti. This constitutes a critical single point of failure, an untenable risk for any sovereign state with pretensions of enduring stability and prosperity.

The narrative of Ethiopia’s defeat is not only premature but fundamentally misunderstands the nation’s strategic chronology. The Ankara Declaration is evidence of this multidimensional engagement. In final analysis, the prevailing narrative surrounding the Ethiopia-Somaliland MoU is a caricature, a simplistic melodrama of victory and defeat that serves only to obscure the complex truths of regional statecraft. Ethiopia’s actions were not those of a rogue state flouting international norms but of a rational actor pursuing its legitimate rights through a mutually beneficial arrangement with a de facto authority.

The international community’s role should not be to enforce a stultifying status quo through pressure but to foster innovative and equitable solutions that acknowledge Ethiopia’s existential needs while promoting regional stability. This requires moving beyond sanctimonious rhetoric and engaging with the world as it is, not as we might wish it to be. Ethiopia’s quest for the sea is immutable. The only question is whether the region will harness this imperative as a catalyst for cooperative prosperity or remain trapped in a cycle of zero-sum confrontation. The ball, as it were, lies not in Addis Ababa’s court alone, but in the international community’s.

By Samiya Mohammed, Researcher, Horn Review

REFERENCES

- Ethiopian Prime Minister issues warning to Somalia, Egypt, Eritrea over Red Sea access https://www.garoweonline.com/en/world/africa/ethiopian-prime-minister-issues-warning-to-somalia-egypt-eritrea-over-red-sea-access

- Former Somaliland president says African Union pressure blocked Ethiopia deal https://www.hiiraan.com/news4/2025/Sept/202809/former_somaliland_president_says_african_union_blocked_ethiopia_deal.aspx

- International law and Ethiopia’s new maritime ambitions https://setit.org/a-persistent-threat-international-law-and-ethiopias-new-maritime-ambitions/

- The Arab Weekly.Eritrea warns Ethiopia against ‘reckless’ push for Red Sea access. https://thearabweekly.com/eritrea-warns-ethiopia-against-reckless-push-red-sea-access

- The Reporter Ethiopia. Ethiopia’s right to the sea under international law https://www.thereporterethiopia.com/44075/

- Wondale, S. Ethiopia’s right to the sea under international law. The Reporter Ethiopia. https://www.thereporterethiopia.com/44075/

- Georgetown Journal of International Affairs. Reshaping the Horn of Africa: Dams, ports, and peace deals. https://gjia.georgetown.edu/2025/04/15/unconventional-transactions-and-alliances-in-the-horn-of-africa-statehood-dams-ports-and-peace-support-operations/

- Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). (2025). Vying for regional leadership in the Horn of Africa. https://www.csis.org/analysis/vying-regional-leadership-horn-africa