18

Aug

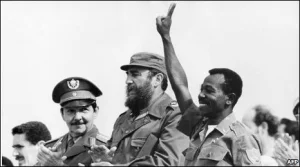

Colonel Mengistu & Fidel Castro: Socialist Revolution and the Dynamics of Land, Leadership, and Social Fabric

In Ethiopia, the red flag of revolution fluttered over empty granaries; in Cuba, it waved over crowded literacy schools. Two revolutions, two socialist experiments, both shaped by Soviet doctrine and born from anti-imperialist fervor, marched into history with promises of liberation and equality. Yet one ended in famine and exile, while the other endured under embargo and scarcity.

Ethiopia under the Derg and Cuba under Fidel Castro entered history with similar slogans and Soviet rifles, but one faltered against the stubborn grain of its soil while the other adapted and persisted. The difference lay not merely in geography or fortune, but in how each revolution navigated the bond between state and society – through land, leadership, war, and the everyday distribution of hope. Understanding why they diverged remains crucial, not to dwell on the past, but to illuminate the present.

The central battlefield of any agrarian revolution is land. In 1975, the Derg nationalized all rural property with the promise of dismantling feudal chains. Yet it ignored Ethiopia’s intricate peasant tenure systems, such as the rist, uprooting centuries of communal practice. Redistribution was dictated by maps in Addis Ababa rather than the consent of farmers.

Forced collectivization and ill-conceived land fragmentation stifled production and destroyed incentives. Villages that had tilled the same fields for generations were commanded to work for the revolution rather than for their households. Resistance emerged – sometimes quietly, in slowed labor, sometimes openly, through armed rebellion.

Cuba approached land reform differently. Breaking the latifundio system was not merely an assertion of state power; it was a staged political theater that acknowledged peasant knowledge. Cooperatives, smallholder farms, and later urban organic gardens during the Special Period maintained production when Soviet inputs vanished. Even under centralized control, Havana fostered local initiative, embedding farmers within the image and endurance of the revolution. When external aid collapsed, these grassroots networks sustained food supply. The lesson is unmistakable: land reform succeeds when it earns the trust of the people.

For Ethiopia today, this translates into expanding agricultural exports and employment opportunities, fostering productivity through participatory mechanisms and indigenous knowledge.

Leadership further widened the gap between the two revolutions. Mengistu Hailemariam’s Derg embodied military Marxism in its most brittle form: governance through purges, the Red Terror, ethnic engineering, and perpetual war mobilization. Villages were uprooted in resettlement campaigns, cultures bulldozed into a single Amharic administrative mold, and all opposition treated as treason. The peasantry was a subject to discipline, not a partner to mobilize. The language of the Derg was command.

Castro, while equally authoritarian, combined coercion with populist performance. His speeches were marathons not merely of rhetoric but of recognition, naming farmers, workers, and teachers as heroes, linking the revolution to tangible gains: free schools, rural doctors, and a collective sense of pride against a hostile world. Mass organizations like the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution functioned as surveillance, yes, but also as social glue, giving citizens a stake in the endurance of the state. Leadership endures when people feel recognized and included; governance today must continue investing in schools, digital services, and healthcare, tangible signs that the state reaches everyday life.

War and militarization further shaped divergence. The Ogaden War of 1977 plunged Ethiopia deeper into a war economy: grain trucks became troop carriers, schools became barracks, famine warnings went unanswered. The Derg’s siege mentality prioritized the military over civilians, treating the nation as a battlefield. Cuba also fought in Angola, and even in Ethiopia itself, but these campaigns were framed as solidarity rather than endless emergency. Military strength must never overshadow civilian needs; Ethiopia today balances infrastructure, trade, and education alongside national security, a balance the Derg never achieved.

External patrons tested both regimes. The Derg relied almost entirely on Soviet arms and economic lifelines, which kept the regime afloat in the Ogaden War and against internal insurgencies, but masked deep economic decay. When Moscow shifted priorities under Gorbachev, Mengistu was left unable to sustain war or loyalty, leading to a swift collapse. Cuba, under Washington’s embargo from the outset, turned siege into identity. When Soviet support vanished, Havana adapted: urban gardens, limited private markets, and recalibrated policies kept society functioning. The lesson is stark: no nation should hinge its survival on a single ally. Ethiopia today diversifies its diplomacy – from BRICS engagement to Gulf partnerships – building resilience in global markets and politics.

Service provision underlined the legitimacy gap. The Derg measured development in quotas on paper even as famine ravaged Wollo and Tigray; trust evaporated. Cuba, even in the economic collapse of the 1990s, maintained clinics and literacy programs. Roads, schools, and clinics are not mere infrastructure; they are the political armor of any state. Ethiopia is currently expanding schools, health insurance, and local capacities, reducing aid dependency while demonstrating governance in daily life.

The Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) that assumed power in 1991 avoided the harshest mistakes of the Derg: no forced collectivization and greater openness to markets. Yet centralization persisted, and perceptions of uneven development endured. Development must not only appear in national statistics; it must be felt in the lived experience of citizens.

Today, Ethiopia’s administrative body pursues a blend of openness and self-reliance. Economic growth is evident in soaring export revenues, strengthened foreign reserves, and millions of new jobs. Fiscal expansion funds agriculture, infrastructure, and disaster relief. Market liberalization, through Ethiopia’s first stock market since Haile Selassie, foreign participation in banking, and telecom reform, reshapes the economy. Infrastructure projects such as the nearly-complete GERD, expressways, and modern urban developments transform connectivity.

The MESOB initiative is digitizing public services for over fifty million users, while green investments – including billions of trees planted – signal a long-term sustainability vision.

These measures reflect a willingness to adapt, the very trait that enabled Cuba’s endurance and whose absence precipitated the Derg’s fall. Ethiopia now has the opportunity to intertwine modernization with the lessons of history: ensuring that growth is measured not only in numbers but in lived realities.

From the fall of the Derg, Ethiopia learns to root reforms in local realities, to balance military and civilian priorities, and to diversify partnerships. From Cuba, it learns to maintain essential services under all conditions, to adapt constantly, and to mobilize people because participation builds resilience. The trajectory from economic modernization to digital governance suggests these lessons are being internalized. Where gaps remain, the path is not destruction but constructive expansion of what works.

Ultimately, the Derg and Castro’s Cuba illustrate a fundamental truth: power detached from the people will sink in the storm, whereas power embedded in the daily lives of citizens can withstand any siege. Today, Ethiopia plants its future in the soil of evidence-based governance, ensuring that revolutionary promise is measured not by slogans, but by the endurance and dignity of its society.

By Surafel Tesfaye, Researcher, Horn Review

Further reading:

- Ottaway, Marina. Land Reform in Ethiopia 1974–1977. African Studies Review, 1977.

- Young, Crawford. The Politics of Revolution in Ethiopia. Cambridge University Press, 1976.

- Rubenson, Sven. The Fall of the Derg and the Ethiopian Civil War. Scandinavian Institute of African Studies, 1991.

- Clapham, Christopher. Transformation and Continuity in Revolutionary Ethiopia. Review of African Political Economy, 1988.

- Lefebvre, Jeffrey. Ethiopia and the Cold War: Dependency and Sovereignty. African Affairs, 2000.

- Bahru Zewde. A History of Modern Ethiopia, 1855–1991. James Currey, 2001.

- Vaughan, Sarah. Coping with Crisis: Social Policies and Rural Famine in Ethiopia, 1973–1985. Journal of Modern African Studies, 1991.

- Paz, J. V. The Cuban Agrarian Revolution: Achievements and Challenges. Revista de Economia Agraria, 2011.

- Kozameh, S. Guerrillas, Peasants, and Communists: Agrarian Reform in Cuba’s Liberated Territories. The Americas, 2019.

- Kapcia, Antoni. Leadership and Legitimacy in Revolutionary Cuba. Journal of Latin American Studies, 2000.

- Sweig, Julia. Inside the Cuban Revolution: Leadership and Military Strategy. Brookings Institution Press, 2009.

- Mesa-Lago, Carmelo. Cuba under Raul Castro: Adaptation and Survival. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005.

- Feinsilver, Jill. Cuba: The Collapse of the Soviet Bloc and the Special Period. Latin American Perspectives, 1993.