12

Aug

The Unipolar Moment and the Divergent Foreign Policies of Meles Zenawi and Isaias Afwerki

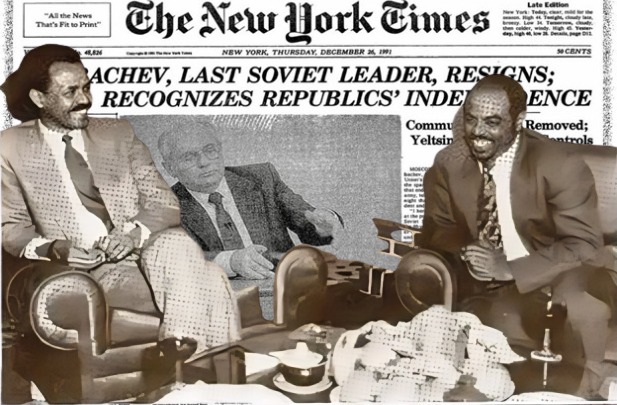

When Meles Zenawi and Isaias Afwerki, both staunch Marxist-Leninists – Stalinists, to be exact – rose to power in Addis Ababa and Asmara respectively, the global political landscape had dramatically shifted from the days of their insurgencies. The Cold War had ended, the Soviet Union had collapsed, and what seemed like a decisive Western victory had ushered in a new era dominated by unchallenged American power. For these two leaders, the transition from rebel movements to state governance demanded a recalibration of foreign policy, but the paths they took diverged sharply. One emerged as a Western ally, while the other embraced an anti-Western posture that led to isolation and antagonism. Understanding how this divergence occurred requires situating their trajectories within the broader global context of the post-Cold War “unipolar moment.”

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 heralded what many interpreted as the triumph of the United States and its Western allies. The ideological and geopolitical rivalry that had defined the second half of the twentieth century appeared decisively resolved in favour of capitalism and liberal democracy. Charles Krauthammer famously termed this the “unipolar moment,” describing an unprecedented period in which the United States stood as the unrivalled global hegemon. The Soviet Union, once a superpower rivalling the US, was reduced to a diminished, second-tier power incapable of projecting influence comparable to Western might.

This shift was not merely symbolic. It was evident in the rapid response to Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990, where a coalition led by the US decisively defeated Iraq’s forces in Operation Desert Storm. Soviet decline had created a global environment where the United States had unparalleled freedom to act militarily. The Horn of Africa and the wider Middle East understood that American power was ascendant; surviving and achieving political objectives increasingly depended on aligning with this new global order. For rebel movements and emerging states alike, the bipolar Cold War framework no longer applied, forcing leaders to navigate a unipolar world dominated by Western interests and norms.

The reverberations of Moscow’s fall were felt acutely across the Red Sea and in the Horn. The weakening of Soviet support directly impacted the failing Derg in Ethiopia, hastening its demise. Both the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) were shaped by the Cold War context, and their victories coincided with the collapse of Soviet influence in the region. The end of the Cold War also marked the termination of the Horn of Africa as a proxy battleground; Soviet retrenchment left the United States as the dominant external actor, though its engagement had historically been more reactive, focused on countering Soviet expansion rather than shaping local dynamics proactively.

Concurrently, the region witnessed profound changes beyond Ethiopia and Eritrea. Sudan underwent a political transformation with the rise of an Islamist government in 1989, while Somalia descended into chaos and anarchy. Yemen’s unification further reflected the shifting regional order. The socialist South Yemen, a Soviet ally, lost its strategic patronage adding to the broad geopolitical reconfigurations triggered by the Cold War’s end and America’s rise.

During their rebel phases, both the TPLF and EPLF sought to position themselves as legitimate alternatives to the collapsing government they opposed. However, their approaches to engaging with the West diverged significantly, reflecting deep historical and ideological differences. The EPLF’s relationship with the West was complicated from the outset. The United States had historically supported Emperor Haile Selassie and opposed separatist movements like the EPLF, perceiving Eritrean secession as a threat to Ethiopian territorial integrity. This legacy contributed to a persistent Eritrean leadership suspicion of Western intentions that persists to this day.

In contrast, the TPLF, through the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), began cultivating ties with the US State Department by the late 1980s. These connections were often mediated through NGOs and think tanks promoting Western political and economic ideas. At the 1991 London Conference, which involved both Meles and Isaias, the West effectively endorsed these former Marxist insurgents as legitimate actors within the emerging liberal international order. The conference emphasized the establishment of inclusive transitional governments and the recognition of Eritrea’s right to self-determination through a referendum—both framed as prerequisites for international legitimacy.

Meles Zenawi returned to Addis Ababa to form a “broad-based and inclusive” transitional government, embracing key Western democratic norms and economic liberalization. Paul B. Henze noted that political dialogue under the EPRDF shifted from rigid Marxism to an emphasis on Western democracy, federalism, and open markets. Similarly, Isaias Afwerki acquiesced to a delayed Eritrean independence referendum in 1993, recognizing the necessity of Western approval for state legitimacy. Both leaders understood that Stalinist ideology had to be discarded in favour of working within the global capitalist order dominated by Western powers.

This post-Cold War environment offered the West a comfortable platform for influence in the Horn of Africa, focused on fostering stability through alignment with liberal democratic and economic principles. However, after coming to power, Meles and Isaias charted radically different courses in their relations with the West.

Meles Zenawi adeptly courted Western support, especially from the 2000s onward. Despite Western insistence on multi-party democracy and fair elections, Meles presented Ethiopia as a “proto-democracy” progressing towards full democratization, a narrative that found resonance in Western capitals. The defining moment came after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, when the United States reprioritized security concerns under President Bush’s global War on Terror. Ethiopia’s decisive military intervention in Somalia against the Islamic Courts Union positioned it as a frontline state against terrorism in the region. By helping to dismantle radical Islamist elements, Ethiopia gained extensive political, economic, and military support from the West, effectively side-lining concerns about democratic deficits.

Moreover, under Meles, Ethiopia’s developmental state model combined strong state intervention with openness to international financial institutions and global markets. This hybrid approach attracted Western aid and investment while maintaining government control over strategic sectors, bolstering Ethiopia’s standing as a stable partner in a volatile region.

In stark contrast, Isaias Afwerki’s Eritrea became increasingly isolated due to its anti-Western posture. Though initially viewed as a potential “Renaissance leader” by some Western observers, Isaias remained deeply suspicious of Western motives, often dismissing aid as a tool for political leverage.

The 1998–2000 war between Ethiopia and Eritrea shattered Western optimism. Eritrea’s decision to initiate conflict tarnished its international reputation. While both countries faced sanctions, Ethiopia managed to rehabilitate its image by demonstrating strategic alignment with Western interests, particularly in counterterrorism. Meanwhile, Eritrea descended further into authoritarianism under the People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ), attracting increased Western condemnation for human rights abuses and further entrenching its isolation.

The legacies of these divergent paths persist into the present as the unipolar moment itself wanes. The rise of China and Russia, along with shifts in US foreign policy under the Trump administration, characterized by disengagement from traditional global commitments and increased rivalry with China, have contributed to the accelerating emergence of a multipolar world order. In this evolving context, both Addis Ababa and Asmara confront new geopolitical realities. Under its new Prime Minister, Ethiopia’s foreign policy discourse increasingly entertains a return to a non-alignment strategy, seeking partnerships beyond traditional Western allies and engaging any actor willing to contribute to its development and security. Meanwhile, Isaias expresses hope for a reassessment of US policy towards Eritrea, remaining in criticism of what he views as a misguided American approach during the past decades.

The contrasting paths of Meles and Isaias illustrate the complex choices rebel movements-turned-states faced in adapting to a Western-dominated post-Cold War order. While Meles embraced engagement and alignment with Western priorities, leveraging global concerns such as terrorism to secure support, Isaias chose isolation and confrontation, which ultimately marginalized Eritrea on the international stage. As the global balance of power shifts yet again, the Horn of Africa’s leaders face the ongoing challenge of recalibrating their foreign policies to navigate a more complex and multipolar world.

By Mahder Nesibu, Researcher, Horn Review

Further Reading

Tekle, A. (1996). International Relations in the Horn of Africa (1991-96). Review of African Political Economy, 23(70), 499-509.

Henze, P. B. (1991). Ethiopia in 1991—Peace Through Struggle (Rand Corporation Paper No. P-7743). Rand Corporation.

Krauthammer, C. (1990, January 1). The unipolar moment. Foreign Affairs.

Adebajo, A. (2012, August 8). Meles Zenawi: Ethiopia’s pragmatic philosopher king or cruel despot? The Guardian.

Dehner, J. (2025, April 28). Eritrea and the West: The Narrative of Victimhood. HORN International Institute for Strategic Studies.

Afwerki, I. (2025, July 25). Interview with President Isaias Afwerki on global and regional issues: Part 1, second segment. Shabait.