12

Aug

Somaliland’s Realities & Somalia’s Chronic Fragility: The Somali Political Equation

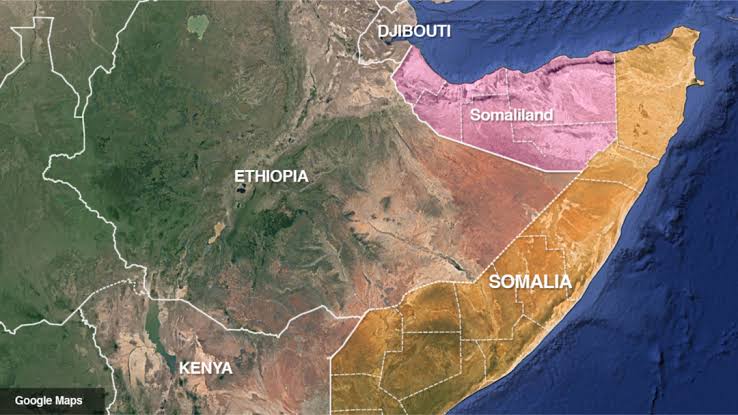

The international community’s persistent depiction of Somalia as a singular, deeply troubled state obscures the starkly different reality in the Horn of Africa. For over three decades, a profound divergence has solidified between the Republic of Somaliland, which has cultivated functional self-governance and relative stability, and the Federal Republic of Somalia, which remains mired in persistent state failure and fragmentation.

Somalia represents symbolic unity that conceals deep fragmentation, while Somaliland embodies genuine unity that is denied by symbolic politics. This assertion aptly captures the existing dichotomy.

Adhering to a symbolic map, rooted more in past aspirations than present realities, is a disservice to Somaliland’s legitimate claims and an impediment to regional peace. This stance limits Somaliland’s access to international finance and aid, constraining its development, while offering a false hope for reunification with a Somalia that lacks the capacity for it.

The current divergence, however, is rooted in distinct colonial legacies. The British Somaliland Protectorate experienced indirect rule, allowing indigenous governance structures to persist. In contrast, Italian Somaliland faced a more direct, assimilationist policy, creating different administrative traditions and political cultures. These differences created inherent incompatibilities when the two territories merged (Hersi, 2018).

Somaliland achieved independence from Britain on June 26, 1960, recognized by 35 countries, including UN Security Council permanent members. This brief sovereignty is crucial to its contemporary claims. The subsequent union with the Trust Territory of Somalia (formerly Italian Somaliland) on July 1, 1960, driven by pan-Somali nationalism, was legally and politically flawed.

Critically, the “Act of Union” was never formally ratified through a bilaterally signed treaty. Somaliland’s legislature passed its “Union of Somaliland and Somalia Law,” but Mogadishu approved a different Act of Union, which was merely in principle and legally insufficient to bind Somalia to Somaliland’s terms. This lack of a proper legal instrument is central to Somaliland’s argument that it is dissolving a questionable compact, not seceding(Trunji, 2020).

The new Somali Republic’s constitution, drafted mainly in the South, was accepted by acclamation without substantive Somaliland input and was rejected by a majority of voters in Somaliland in the 1961 referendum (over 60% against). The union quickly became unequal, with Somaliland marginalized politically and economically, leading to an attempted coup by Somaliland officers in December 1961 (Hersi, 2018). Somaliland frames its 1991 re-declaration of independence as a restoration of sovereignty, not secession.

Three Decades of Divergence: State-Building in Somaliland, State Collapse in Somalia

The 1991 collapse of Siad Barre’s dictatorship, which had unleashed atrocities against the Isaaq clan in Somaliland (including the 1988 bombing of Hargeisa and Burao ), led Somaliland to declare the restoration of its independence on May 18, 1991.

Somaliland then embarked on a remarkable indigenous, bottom-up peacebuilding and state-formation process, relying on traditional elders and community consensus, exemplified by the Borama Conference of 1993. This contrasted sharply with externally driven efforts in southern Somalia. Relative ethnic homogeneity and a shared experience of persecution under Barre likely fostered social cohesion.

Somaliland established a hybrid democratic system, adopting a constitution via a 2001 referendum (97% support ), holding multiple elections, and developing its own security forces that have maintained internal peace and acted as a bulwark against extremism (Hersi, 2018). Despite lacking international recognition, which bars access to significant aid and investment, Somaliland has cultivated a resilient economy based on livestock exports, remittances, and strategic partnerships like the DP World development of Berbera Port. The absence of large-scale external aid may have fostered self-reliance.

Conversely, Somalia plunged into over three decades of civil war, warlordism, and humanitarian crises. Numerous internationally sponsored transitional governments failed to establish a stable national authority. These interventions often lacked local legitimacy and sometimes empowered conflict entrepreneurs. Somalia’s federal model is contentious and ineffective, with disputes between the Federal Government (FGS) and Federal Member States (FMS) like Puntland. Al-Shabaab’s insurgency continues to plague large areas, necessitating international peacekeeping (ATMIS). Somalia’s economy is aid-dependent, with rampant corruption and minimal service provision.

Somaliland is not without challenges, including territorial disputes in Sool, Sanaag, and Cayn (SSC) regions, election delays, and human rights concerns (press freedom, minority clan marginalization, and religious freedom). However, it possesses functional state mechanisms to address these, unlike Somalia.

Somaliland fulfills the Montevideo Convention criteria for statehood: a defined territory, permanent population, effective government, and capacity for international relations, evidenced by liaison offices and agreements like the Berbera port deal and the Ethiopia MoU (Schaefer, 2023; Somaliland Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2024). Its legal claim rests on restoring the sovereignty recognized in 1960, arguing the voluntary union with Somalia was legally flawed and never properly ratified. A 2005 AU fact-finding mission reportedly noted the unique circumstances and “questionable” legal basis of the 1960 union (African Union, 2005). The principle of uti possidetis juris (inviolability of colonial borders) can also support its claim to the former British Somaliland boundaries (Schaefer, 2023).

The international reluctance, particularly from the AU, fearing a “Pandora’s Box” of secessionism, often overlooks Somaliland’s sui generis (one of a kind) case, distinct from unilateral secessions. The AU’s inconsistency is evident when compared to its admission of Western Sahara. Prioritizing Somalia’s nominal territorial integrity over Somaliland’s demonstrated stability rewards state failure and penalizes successful indigenous governance.

In the volatile Horn, Somaliland is a pragmatic partner in regional security, combating piracy and terrorism. Its strategic Gulf of Aden location underscores international interest in its stability. Recognition could unlock its economic potential and strengthen its security role. Continued non-recognition contributes to regional instability by leaving its status unresolved.

A Call for a Reality-Based International Stance

For three decades, Somaliland has built a functioning de facto state with relative peace and democratic institutions, while Somalia remains mired in state failure and conflict despite extensive international aid. The international fiction of a single Somali state ignores this profound divergence.

A pragmatic, reality-based international policy is needed. The international community, including the AU, must seriously consider Somaliland’s quest for recognition, acknowledging its achievements. This could offer a precedent for engaging with protracted state failure alongside successful de facto statehood, prioritizing peace, stability, and effective governance.

Recognizing Somaliland would legitimize a successful African-led peacebuilding model, enhance regional stability, unlock its economic potential, and uphold self-determination for a populace that has demonstrated capacity for responsible self-governance. The day will come when the world must acknowledge the political realities that have taken root.

By Tsegaab Amare, Researcher, Horn Review

References

- African Union. (2005). AU fact-finding mission to Somaliland (30 April – 4 May 2005). Archived on Somaliland Law. https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/PDFFiles/au-fact-finding-mission-to-somaliland-30-april-to-4-may-2005.pdf

- Hersi, M. F. (2018). State fragility in Somaliland and Somalia: A contrast in peace and state building. International Growth Centre. https://www.theigc.org/sites/default/files/2018/08/Somaliland-and-Somalia_online.pdf

- Schaefer, M. (2023). Somaliland and the need to update international law on statehood recognition. Michigan Journal of International Law. https://www.mjilonline.org/somaliland-statehood-recognition/

- Somaliland Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2024, January). For immediate release: The Republic of Somaliland government signs a memorandum of understanding with the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Ministry of Foreign Affairs & International Cooperation. https://mfa.govsomaliland.org/article/immediate-release-republic-somaliland-government-signs-memor

- Trunji, M. I. (2020). The legal wrangling over the 1960 act of union between the two states of Somaliland and Somalia. Somaliland Sun. https://somalilandstandard.com/the-legal-wrangling-over-the-act-of-union-between-the-two-states-of-somaliland-and-somalia-in-1960/