31

Jul

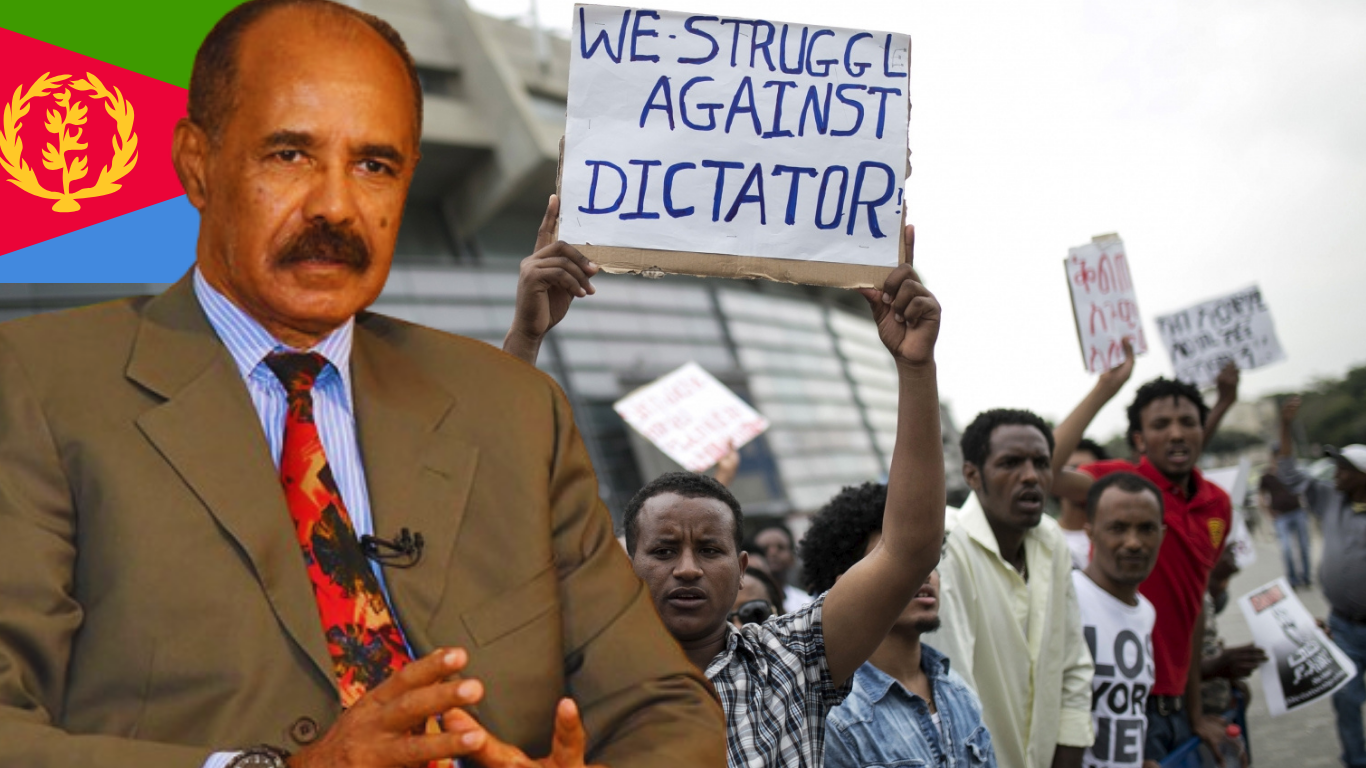

Peace Built on Sand: Why Eritrea’s Dictatorship Must Fall Before Any Peace and Integration Can Rise

By Dr. Tomas Solomon

Ambassador Dina Mufti’s recent article, “Transcending the Ethio-Eritrean Conundrum: A Vision for a Better Tomorrow,” offers some thoughtful approaches to the complex relationship between Ethiopia and Eritrea. He nailed the core dilemma perfectly: our two nations are so deeply intertwined culturally, historically, and socially that completely separating feels impossible. Yet, our Eritrean identity, created through a colonial legacy coupled with a liberation struggle, means we can’t just easily become one again. The conundrum he pointed out is something every Eritrean understands.

The Ambassador’s piece rightly highlights our shared interdependence. He discusses the practical benefits of economic ties, security interests, and even Ethiopia’s persistent desire for sea access through Assab. These are all valid points that highlight how much both nations could gain from genuine cooperation rather than isolation. What’s particularly creative about his vision is the idea of a gradual, step-by-step supranational framework, built on economic coordination, political discussions, defense cooperation, and cultural exchange. This incremental approach acknowledges our fractured history and the need to rebuild trust and institutional capacity over time. His call for international support to nurture this vision and deter spoilers is also a wise and pragmatic suggestion.

However, as an Eritrean activist, I’ve got to point out the giant elephant in the room that this otherwise constructive framework dangerously overlooks: Isaias Afwerki’s dictatorial regime. The Ambassador claims that “the governments of Eritrea and Ethiopia are the principal actors without whose leadership this vision can never be realized.” This isn’t just dangerously optimistic; it’s highly inaccurate. The Isaias regime isn’t a credible or reliable partner for peace. It’s an authoritarian state that has systematically dismantled every institution, crushed all dissent, wiped out the rule of law, and caused mass poverty, forced conscription, and a devastating exodus of our youth.

The idea of “bold leadership from both sides” just doesn’t fly when one side, Eritrea, has no legitimate or accountable government to begin with. The regime in Asmara isn’t answerable to its people, nor is it genuinely interested in regional stability unless it directly helps its own survival. No matter how appealing the promises of economic integration or cultural cooperation might sound, you simply can’t build them on the shifting sands of dictatorship. A supranational union built on such an imbalanced foundation would be inherently unstable, doomed to repeat the very cycle of violence it’s supposed to break.

Furthermore, the article significantly underplays the crucial role of democratic reform. It mentions “deficits in institutional capacity and rule of law” as if they are isolated challenges rather than central and systemic failures. But let’s be real: no sustainable economic or political union can survive without transparency, accountability, and the democratic will of its citizens. None of these exist in Eritrea today. Forcing an integration that includes a one-party state built on coercion would only create an unequal, unsustainable partnership, deepening tensions instead of resolving them.

Then there’s the really tricky part: the idea of a supranational authority superseding state powers, especially in economic matters. This remains a sensitive issue for many Eritreans, whose sense of national identity is shaped by the legacy of the struggle for sovereignty, often at the expense of genuine human development and the population’s well-being. How do you deal with that? It’s even more problematic when such arrangements are proposed without legitimate representation or democratic consultation. Similarly, the notion that Ethiopia would gain exclusive rights to manage Assab, while perhaps pragmatic for some, could easily be interpreted as a concession granted under pressure, rather than a truly mutually beneficial agreement built on shared ownership and trust.

The article gestures toward reconciliation, but offers limited guidance on how this might be achieved at the grassroots level. While youth exchange programs are mentioned, concrete proposals are missing for truth-telling and fostering deeper societal bonds. This is particularly difficult given that civil society in Eritrea is virtually nonexistent, and any cross-border interaction is tightly controlled by the regime, making genuine social integration impossible.

Despite these critical gaps, the opportunities Ambassador Dina Mufti highlights, such as shared prosperity, regional stability, stronger cultural ties, and less foreign interference, are real and worth pursuing. But here’s the unavoidable truth: these positive outcomes depend entirely on addressing the core obstacle — the regime in Asmara.

For any integration to be viable and truly win-win, the removal of the Isaias regime isn’t just a good idea; it’s a fundamental prerequisite. This regime is simply incapable of genuine partnership because its decisions are driven solely by its survival, not the welfare of the Eritrean people. Any agreements made under its watch would lack public legitimacy, making them fragile and prone to collapse. Internally, the regime’s oppressive policies have hollowed out the country, leaving Eritrea without the basic stability needed to uphold its side of any supranational deal. Externally, Isaias has consistently played the role of a regional spoiler, meddling in Ethiopia’s internal security, which completely contradicts the spirit of cooperation that integration demands.

Even the economic logic of integration falls apart under a dictatorship. The Eritrean regime’s secretive and exploitive economic model means any potential benefits would just be hoarded by the ruling elite, not distributed to the public. A democratic Eritrea, on the other hand, could truly take advantage of these economic opportunities to improve lives, attract legitimate investment, and build much-needed trust. The deep trust deficit, stemming from Eritrea’s history of broken promises and erratic foreign policy under the current regime, also makes a complex supranational project requiring high levels of legal and political reliability simply unfeasible.

So, while Ambassador Dina Mufti’s article presents a potential framework for a win-win situation, it largely glosses over the fundamental political reality in Eritrea that makes such a framework impossible to implement authentically right now. The nature of the Eritrean regime isn’t a minor challenge to be worked around; it’s the primary obstacle that must be removed before any meaningful or lasting peace can even begin to rise. That’s why I argue that calling for the removal of Isaias Afwerki’s regime isn’t an act of aggression, but an act of strategic clarity and a moral imperative. Only a democratic Eritrea can bring its people to the table in good faith, genuinely contribute to regional peace, and engage in a partnership of equals with Ethiopia. The Ambassador’s framework is a useful blueprint, but it has to be grounded in the reality that Eritrea can’t transcend the conundrum while its people remain in chains. Democratic transformation isn’t some far-off dream; it’s the absolute precondition for everything the Ambassador proposes. Without it, the dream of peace and integration will remain exactly that: a dream built on sand.

About the Author

Dr. Tomas Solomon is a data scientist and engineer with over decades of experience in advanced analytics and application development. He holds a doctorate in Engineering Management from George Washington University and master’s degrees in Advanced Analytics and Computer Networking. Dr. Tomas Solomon is also the author of The Unlikely Journey: From a Child Soldier in Africa to Tech Director of a Major Corporation in America, which reflects on his early life in Eritrea. He regularly engages in the country’s politics and its trajectory. His writing engages with questions of governance, authoritarianism, and the long-term impact of conflict