30

Jul

Anchoring Unity in Representations: Rethinking Party Standards in Ethiopia

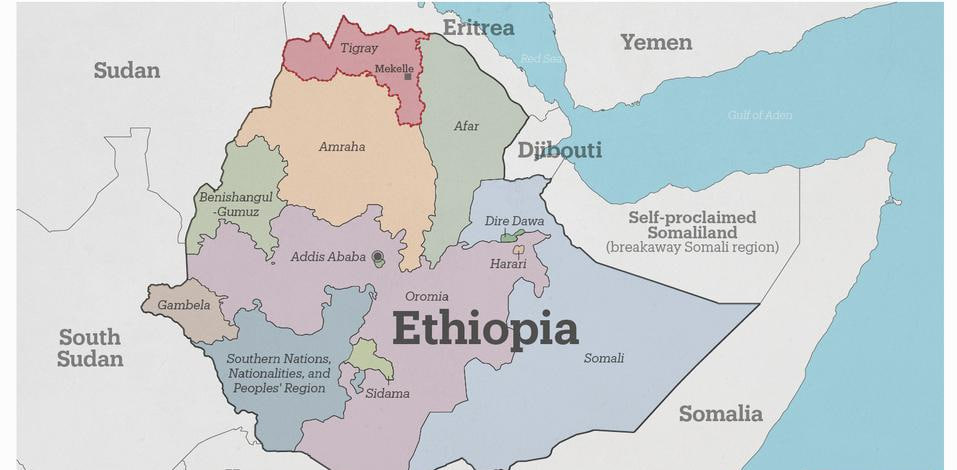

Ethiopia’s path to democratic consolidation is influenced by its institutional decisions and historical conflicts. Proclamation No. 1162/2019, which governs the registration of political parties and electoral conduct, contains one of the key requirements in its electoral framework. It requires a political party to show support not only from its region of origin but also from six other regional states to be registered as a national party. This, along with the rule that founding members must be at least 10,000 in number, spread across zones, regional states, and special woredas, is meant to ensure national political participation for the country’s federal nature. Although 71 parties have registered both nationally and regionally as of 2024, many struggle to meet these standards (The Global Observatory).

In federal states like Ethiopia, which is home to more than 80 ethnic groups and has an administrative structure based on Ethno-territorial autonomy, the requirement that national parties show support from at least six additional regions beyond their origin is essential. This rule recognizes that Ethiopia’s leadership needs to reflect its diversity both institutionally and rhetorically. The rule establishes a crucial filter by requiring parties to show that they can appeal across various political areas. This distinguishes between parties that can get broad support from those that rely on identity-driven factions. This framework promotes long-term incentives to establish interethnic political coalitions. It encourages a civic approach in parties and promotes platforms that emphasize shared national goals like development, peace and justice. This model directs electoral competition toward building consensus in contrast to the system that allows fragmented representation to dominate. To put it in brief, it is the best way to root national interests in a context where ethnicity plays a significant role and must be overcome if Ethiopia is to continue to exist and thrive as a single federal republic.

Building National Cohesion Through Electoral Design

Ethiopia’s ethnic federalism has strengthened political compartmentalization over time, when it was supposed to empower diverse groups. Parties often find it easier, and more lucrative politically, to rally support from their ethnic or regional bases. But this has exacerbated polarization and weakened the national political center. This logic was intended to be altered by the regional support rule. The law requires a national party to exhibit broad geographical legitimacy in an attempt to promote a more inclusive political environment, where parties must compete across cultural, ethnic and linguistic barriers. This relates to a larger state-building that views political competition not as a platform for identity-based disputes but as a venue for shared national interest. Similar electoral mechanisms are seen in divided societies. For instance, Nigeria’s presidential candidates are required to receive at least 25% of the vote in two-thirds of the states, which encourages coalition building and limits majoritarianism (International IDEA, 2021). To avoid the dominance of Java-based elites and to promote inclusion from its outer islands, Indonesian parties must meet regional representation criteria to run in the national election.

For Ethiopia, this requirement intentionally seeks to break the cycle of parties that focus narrowly on ethnic grievances and promote those that aspire to lead the country as a whole. It forces parties to create alliances, structure, and stories that appeal to people beyond their core support. This is a democratic declaration of what it means to be a national party in a multinational federation. Ethiopia’s chance of a lasting peace is threatened by the possibility of a return to fragmented, zero-sum competition in the absence of such a rule. Critics rightly raise concerns about the rule’s demands, but that very demand serves its purpose: parties that want to rule all Ethiopians must be able to organize among all Ethiopians.

From Policy Principle to Political Practice: Institutionalizing Fair Access

The rule’s effectiveness depends on how it is implemented, not on its unifying intentions. In reality, many smaller and regional parties encounter significant hurdles that are related to logistics, finance, and security rather than ideology. Reports from Human Rights Watch (2024) and the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (2024) indicate that political activists in contested areas often face arrest, intimidation or restricted areas, especially in places where incumbent authorities are firmly established, like Amhara, Oromia, and Tigray, where there have been ongoing tensions and displacement. It is practically impossible for opposition groups to safely verify supporters or run signature campaigns. This situation raises valid concerns about the fairness of the process. The rule’s intended unifying effect may worsen political disenfranchisement if the rule only applies to well-funded, incumbent-aligned parties.

However, these challenges are not criticisms of the rule per se, but against its uncontextualized enforcement. The National Electoral Board of Ethiopia (NEBE) must have the authority and adequate resources to adjust the rules without losing its core objective. To give parties that demonstrate a credible intent to expand their reach to multiple regions, the board could first introduce a phased registration approach, granting provisional national status. To fulfil the requirements, these parties could be monitored and helped for a predetermined amount of time. Second, a formal coalition provision could be established that allows several regionally strong parties to register together under a unified national platform. This would uphold the inclusive objective without compromising pluralism for homogeneity. Third, especially in rural or conflicted areas where digital access is scarce, digital tools for signatures should be gradually introduced, blending online submission with paper-based outreach.

These reforms would allow the law to serve not as a barrier but as an incentive for national growth. Furthermore, public funding mechanisms could be linked to regional outreach achievements, rewarding parties that exhibit observable engagement across multiple regions. Such support networks are particularly crucial in post-conflict democracies where incumbents retain disproportionate control, according to the African Union Electoral Observers (2022). Ethiopia is no exception. The legitimacy of the rule would be preserved by technical reforms accompanied by political will, which would uphold the rule’s legitimacy while ensuring no genuine actor is excluded from the democratic process.

Recalibrating the Center Without Erasing the Margins

Ethiopia’s requirement for national parties demonstrates that multi-regional support should be seen as a framework that challenges parties to extend beyond their comfort zones rather than as an undemocratic barrier. In a diverse and politically fragile country like Ethiopia, unity can not emerge from majoritarian dominance or rhetorical appeals; rather, it must be institutionalized through electoral design that acknowledges the nation’s complexity. The support rule keeps the national contest from turning into a competition among candidates with limited backgrounds, each claiming to represent everyone while being rooted in specific identities. It embodies Ethiopia’s need for centripetal politics in a historically centrifugal system.

However, this principle needs to be supported by trustworthy institutions, fair enforcement, and flexibility that considers Ethiopia’s changing security and infrastructure challenges. The current administration has a chance to elevate this rule as a pillar of national unity by investing in the circumstances that allow all serious political actors to meet it. This includes coalition-friendly legislative transformations, political education, regional outreach facilitation and granting real autonomy to NEBE. NEBE has recently held discussions with political party leaders concerning amendments to Proclamation No. 1162/2019, to make sure that all electoral laws are inclusive and in favor of a proportional political party. The future of Ethiopian democracy will not rest on rules alone but on how fairly and wisely they are put into practice. When properly applied, the regional support standard can become a bridge that connects pluralism and unity, as well as representation and responsibility.

By Tselot Getachew and Bezawit Eshetu,Researchers,Horn Review

Reference

- African Union. (2022). Report on electoral assistance to member states.

- Ethiopian Human Rights Commission. (2024). Hate speech and disinformation trends in Ethiopia.

- Freedom House. (2022). Freedom in the World 2022: Ethiopia.

- Human Rights Watch. (2024). Ethiopia: Events of 2023.

- International Crisis Group. (2023). Elections and democratic stability in divided states.

- International IDEA. (2021). Electoral System Design Database.

- NEBE (National Election Board of Ethiopia). (2019). Political Parties Registration and Electoral Code of Conduct Proclamation No. 1162/2019.

- The Global Observatory. (2024). Tracking political parties and electoral dynamics in Ethiopia.