13

Jul

Partners or Rivals?: Ethiopia’s New Development Agenda and Discourse of cooperation in the Horn of Africa

Development is about the comprehensive improvement in the quality of life for a people. It encompasses advancements in education, healthcare, sanitation, income levels, and various other critical indicators. In today’s global landscape, continents such as Europe and North America, along with nations in the Far East, are typically classified as developed, while many states within sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America continue to grapple with underdevelopment. However, even among underdeveloped regions, some areas have made significant strides while others have stagnated or even regressed.

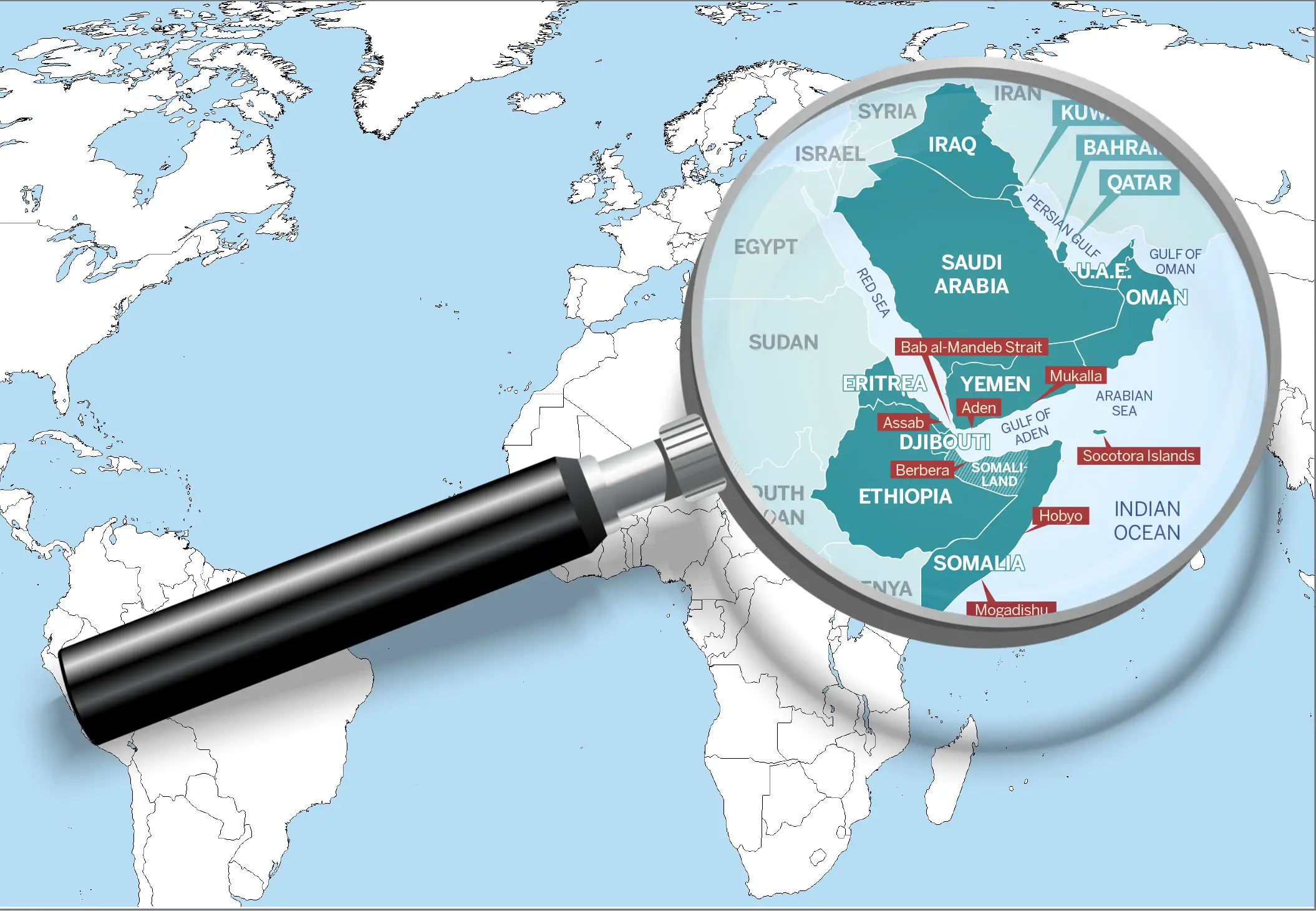

The Horn of Africa, unfortunately, remains firmly entrenched within the underdeveloped category. Home to over one hundred and fifty million people, the region faces a complex web of challenges, including limited infrastructure, poor connectivity, and a persistent vulnerability to both human-caused and natural disasters. Regional integration among states is also alarmingly low because of political divisions, unwilling political actors, and the lingering consequences of protracted conflicts.

The persistence of underdevelopment in the Horn of Africa would be less surprising if confined to the mid-20th century. This a period was known for colonial domination across much of the continent and the nascent independence of others. During this era, external pressures significantly constrained the ability of Horn countries to formulate and implement their own development policies and strategies. Colonial-era extractive institutions remained largely intact, continuing their primary function of enriching their respective colonial powers at the expense of local populations.

Also, the continued underdevelopment of the Horn region into the last quarter of the 20th century could not be that much surprising in the same way. This period was characterized by frequent intrastate and interstate conflicts, resulting in devastating consequences including significant loss of life, widespread disruption of economic activity and resource allocation, mass displacement of populations, and substantial costs associated with reconstruction and the return to normalcy. These states were transitioning away from their Cold War alignments, which had often involved aligning with either the USSR or the USA, giving rise to proxy conflicts and further destabilizing the region.

Regrettably, these dire conditions persist as a defining characteristic of the Horn of Africa today. The region remains plagued by states teetering on the brink of collapse, alarmingly high rates of school dropouts among children, and a vast population struggling with impoverishment. States actively undermine one another’s interests by rejecting opportunities for cooperation, inviting external actors into the region at the expense of exacerbating its complex political dynamics, and cultivating conditions that could ignite conflict at any moment.

Given that past approaches have demonstrably led only to devastation, a fundamentally profound shift in Ethiopia’s development discourse has emerged with offering the potential to reshape prevailing perceptions. This shift is rooted in a renewed emphasis on Ethiopia’s need for access to the sea due to its large population, the perceived injustice of its historical loss of maritime access, and its strategic proximity to the Red Sea region.

While this renewed emphasis on maritime access may be construed by some as a form of irredentism, or an attempt by Ethiopia to forcibly seize territory from its neighbors in violation of their sovereignty, a closer examination of statements made by Ethiopian leaders to various stakeholders, discussions held on public television, and scholarly articles published during the height of this debate reveals a more nuanced perspective. Ethiopia has consistently emphasized that sustainable development is only possible through a spirit of mutual cooperation which departs from past practices that involved rejecting dialogue and perceiving such discussions as a threat to national sovereignty.

Ethiopia has affirmed that development is a fundamental right for all nations and that achieving this right necessitates constructive engagement and negotiated agreements on critical issues such as access to the sea. This assertion is supported by the increasing volume of global trade, the growing mobility of goods and services, and the interdependence of nations on the production capabilities of others. Secure access to this global system, through a route managed independently and that reduces reliance on others, is therefore deemed essential.

Even within the African context, the vast majority of states import more goods than they export. These imports include essential commodities such as medicines, petroleum and gas, and other vital resources that are crucial for sustaining both the national economy and the daily lives of citizens. Any disruption to these supply chains is akin to placing a hand on a person’s throat, severely impeding their ability to breathe. Ethiopians experienced this firsthand with the onset of the Russia-Ukraine war and the ongoing conflicts in the Middle East, which resulted in reduced accessibility to petroleum (let alone increased prices), delays in fertilizer transportation, and a significant rise in the cost of living.

These factors shows the growing interdependence of the global community, where no nation can thrive in isolation. However, this reality has not been fully embraced by all states in the Horn of Africa. With the exception of Ethiopia, all other states in the Horn of Africa have direct access to the sea and significant coastal territories. However, it is also true that many of these coastal areas have not yet achieved their full development potential. Consequently, Ethiopia’s pursuit of maritime access is often misconstrued as a territorial claim, with neighboring states failing to acknowledge the underlying developmental imperatives driving this agenda.

Ethiopia has articulated a clear vision for achieving maritime access through collaborative negotiations, offering a range of potential concessions based on the preferences of willing partner countries. These options include land swaps, joint mega-projects, shared ownership in state-owned enterprises such as Ethio Telecom or Ethiopian Airlines, and other mutually beneficial proposals. It is imperative, however, to move beyond dismissive characterizations of this pursuit as a mere luxury and instead recognize it as a fundamental requirement for sustainable economic development.

Borders, while serving as internationally recognized demarcations to manage territorial claims, should not be viewed as barriers to development. They functioned effectively in a past era when state economies were smaller and less susceptible to global shocks. However, in our interconnected century, cooperation is essential, even to the point of re-evaluating long-held assumptions and beliefs about national boundaries. Ethiopia is demonstrating this commitment.

The other states in the Horn of Africa should take note: Ethiopia is not operating covertly to destabilize the region and seize territory. Rather, it is openly expressing its willingness to engage in dialogue to find mutually agreeable solutions. This represents a new paradigm for the region and offers a beacon of hope for the future. It is time to learn from the failures of the past and embrace bold actions that can reverse the tide of underdevelopment and conflict.

By Yabsira Yeshiwas,Researcher,Horn Review