5

Jun

Re-evaluating the French Presence in the Horn of Africa

Ethiopia holds a unique place in African history. While many African nations experienced direct colonial rule during the Scramble for Africa, Ethiopia preserved its sovereignty through a combination of strategic diplomacy and military resistance – most notably demonstrated in the 1896 victory over Italy at the Battle of Adwa. This episode continues to be a source of historical significance and national reflection.

Yet, avoiding direct colonization did not insulate Ethiopia from the broader influences of global power dynamics. While some European powers pursued territorial control through conquest, others, including France, shaped outcomes in the Horn of Africa through diplomatic and strategic engagement. These approaches, though less overt, have had lasting implications – especially with regard to regional access and geopolitical balance.

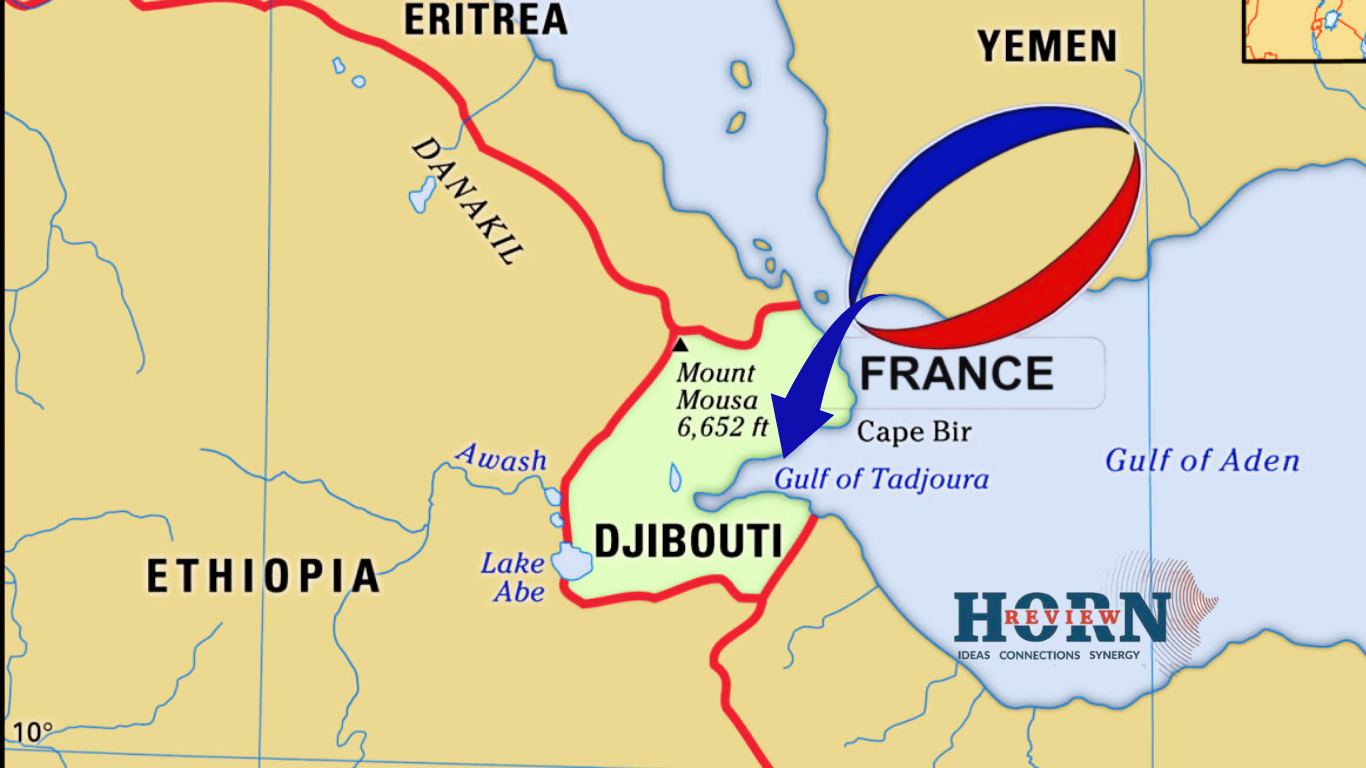

France’s historical role in Djibouti, a territory adjacent to Ethiopia’s eastern frontier, is one such example. French involvement in the area ultimately led to the establishment of Djibouti as a separate colonial entity and, later, an independent state. For Ethiopia, this development had strategic implications: it became a landlocked country, reliant on external ports for maritime trade and regional access. While this reality emerged through legal agreements and complex historical processes, the long-term impact on Ethiopia’s connectivity and economic options has been considerable.

France’s growing presence in the Horn of Africa during the late 19th century can also be understood in a broader geopolitical context. As France faced increasing competition and resistance in West Africa – from rival colonial powers and rising indigenous movements – its strategic priorities began to shift eastward. The Red Sea, and particularly the Bab al-Mandab strait, became a focal point of French maritime and military interest.

Djibouti, situated at this critical juncture between the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, offered France a valuable foothold for projecting influence in a region that was less saturated by European powers at the time. Its proximity to trade routes and imperial shipping lanes made it a natural site for port development and military logistics. Unlike in West Africa, where France often encountered deeply entrenched local structures and competing colonial claims, the Horn offered a relatively open frontier – albeit one adjacent to a sovereign Ethiopia.

This eastward pivot, while not openly confrontational toward Ethiopia, nonetheless introduced new dynamics that would reshape regional power balances. France’s diplomatic engagement in the Horn, combined with its formal establishment in Djibouti, reflected both a response to setbacks elsewhere and a deliberate effort to maintain relevance in an evolving imperial order.

More recently, France’s military and diplomatic setbacks in parts of West Africa – including Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger – have once again redirected French strategic focus toward the Horn of Africa. As a result of popular discontent, security tensions, and shifting political alignments, French troops have been expelled or pressured to withdraw from key West African states. In this context, Djibouti – where France maintains its largest overseas military base – has become an even more critical asset for preserving French influence on the continent. This renewed emphasis reinforces the Horn’s long-standing function as a geopolitical fallback for France. For Ethiopia, this changing dynamic reinforces the need to carefully reassess its regional options and sovereignty in light of growing international entrenchment next door.

The arrangement between France and Ethiopia, including the 1897 treaty signed during Emperor Menelik II’s reign, reflected the norms and power dynamics of the era. While the treaty stipulated certain understandings regarding territorial integrity and third-party claims, the eventual outcome – Djibouti’s continued separation and independence – was not actively contested by Ethiopia in the post-colonial period. Whether due to diplomatic constraints, shifting priorities, or geopolitical realignments, this episode is worth revisiting in discussions about regional sovereignty and strategic access.

Today, Djibouti plays a central role in the region’s geopolitical landscape. As a host to multiple international military bases, the country sits at the crossroads of major global interests near the Bab al-Mandab strait. Ethiopia, by contrast, remains reliant on negotiated port access, and its room for maneuver in this critical zone has narrowed. While cooperation with Djibouti remains essential and generally positive, the broader legacy of the colonial-era boundary arrangements still informs Ethiopia’s position in the region.

This is not to diminish the benefits that Ethiopia and France have enjoyed through cultural, educational, and economic partnerships. Indeed, France has contributed significantly to Ethiopia’s intellectual and institutional development in various fields. However, the conversation about historical legacies should also include a balanced and open dialogue about the long-term regional effects of colonial-era decisions.

One of the challenges is the contrast in public awareness. While Italy’s failed attempt at colonization is widely understood and remembered in Ethiopia, the subtler outcomes of French diplomacy in the region are less frequently discussed. This may be due, in part, to the enduring nature of soft power and the tendency of more indirect strategies to escape the scrutiny that military aggression often invites.

This reflection is not intended as a critique of any nation, nor is it a call to reopen historical grievances. Rather, it aims to encourage a deeper understanding of how past events continue to shape current geopolitical realities. Ethiopia’s development and regional integration require not only economic investment and infrastructure but also historical awareness and informed diplomacy.

As Ethiopia charts its future, it will need a new generation of leaders and citizens equipped to navigate complex regional relationships -leaders who can represent national interests effectively in global forums and advocate for a more equitable arrangement of resources and access.

In that spirit, there is an opportunity for France, as a long-standing partner, to engage in constructive dialogue with Ethiopia around shared history and mutual interests. Strengthening cooperation on equitable terms, especially in areas such as maritime infrastructure, education, and cultural exchange, could serve as a positive step forward.

A clear-eyed understanding of the past is not about blame – it is about building mutual respect, restoring balance, and preparing for a future shaped by cooperation and shared responsibility.

By Markos Haile Feseha,Researcher,Horn Review