31

May

Baghdad’s African Pivot: A New Opportunity for Strategic South–South Partnership

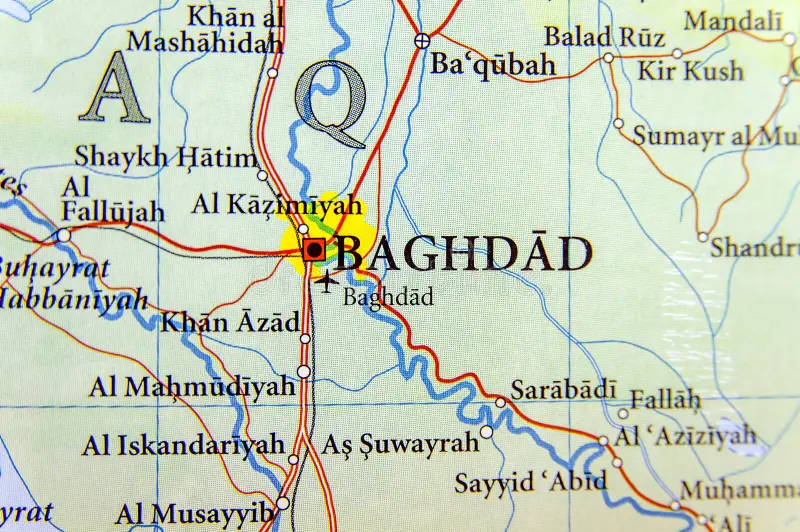

In May 2025, Iraq hosted African Union Commission Chairperson Mahmoud Ali Youssouf in Baghdad, coinciding with the 34th Arab League Summit. While the occasion marked a symbolic return of Africa to Baghdad after more than two decades, it also offered a glimpse into shifting geopolitical realities. As Iraq repositions itself following a decade of internal consolidation, African nations are expanding their global engagement with a renewed focus on strategic independence and diversification. The encounter between Iraq and the African Union reflects more than bilateral courtesy—it signals a recalibration of international partnerships grounded in mutual interest, continental vision, and a growing assertion of African agency.

Iraq’s decision to host the AU’s top official signals both ambition and calculated outreach. Baghdad is seeking to escape the narrow parameters of its post-2003 foreign policy, which has been largely defined by U.S. intervention, Iranian influence, and regional instability. In extending its hand to Africa, Iraq is engaging a continent that no longer enters diplomatic spaces as a junior partner but as a bloc increasingly confident in its demands. With the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) gaining traction and Agenda 2063 setting a clear path toward political and economic self-determination, Africa is defining its relationships abroad with greater clarity. As African states pursue alternative pathways in a multipolar world, interactions like this one in Baghdad are being evaluated less on legacy ties and more on strategic return.

The Iraq–Africa conversation touches key areas of convergence. Economic cooperation, particularly around infrastructure and logistics, is central. Iraq’s $17 billion “Development Road” project envisions a high-speed transit route from the Persian Gulf to Europe through Iraq and Turkey. Though not originally tailored for Africa, this initiative offers potential synergies. African exporters, particularly from East and North Africa, could benefit from interlinked trade corridors if properly negotiated. For Iraq, the connection offers diversification and the chance to play a role in Africa’s global supply chain integration. For African nations, it represents another node in the growing network of South–South economic exchange.

Security dialogue is another pillar. Iraq’s long battle with insurgencies and terrorism presents possible lessons for African states confronting violent extremism in the Sahel, the Horn of Africa, and Central Africa. Counter-terrorism collaboration, intelligence sharing, and technical training offer targeted, pragmatic forms of engagement. Yet African states must enter such arrangements with eyes open—ensuring that such cooperation remains grounded in national sovereignty, avoids over-securitization, and serves local developmental priorities.

Equally important is Baghdad’s symbolic role in opening up space for Afro-Arab diplomacy to evolve. Historically, Arab–African relations have been marked by rhetorical solidarity but shallow strategic commitment. The presence of the African Union Commission Chairperson at the Arab League Summit underscores a potential turning point. The Arab League’s announcement of a $40 million reconstruction fund—largely aimed at Gaza and Lebanon—signals that regional resources can be mobilized with purpose. African states should not only observe but also shape how such resources are conceptualized and deployed, ensuring that Afro-Arab forums serve more than ceremonial ends.

Africa’s diversification strategy, however, must proceed with caution. While Iraq’s outreach reflects a promising shift, it remains a fragile state navigating complex internal politics and external entanglements. For African nations, engagement with Iraq must be driven by clear objectives, measurable outcomes, and the confidence to walk away if interests are not served. Moreover, Africa’s institutional readiness remains a concern. The African Union continues to face structural limitations in terms of financing, enforcement, and coordination among member states. For this new wave of partnerships to materialize into results, the continent must pair ambition with capacity—both at national and continental levels.

The broader international context provides momentum for such realignments. The retreat of traditional Western partners, especially under the “America First” doctrine of the Trump administration, accelerated Africa’s global diversification. While U.S. initiatives such as Prosper Africa and AGOA maintain relevance, they are no longer seen as the only gateways to opportunity. African states are increasingly engaging with China through the Belt and Road Initiative, with Turkey and the Gulf through investment diplomacy, and with non-traditional partners such as India, Russia, and now Iraq. This shift is not ideological. It is strategic—a response to the need for redundancy, resilience, and return on partnership.

Country-level examples further illustrate this assertiveness. South Africa, as a BRICS member, balances its deep Western economic ties with non-alignment. Ethiopia, through infrastructure development and independent policy-making, maintains engagement with both China and the West. Rwanda’s partnerships with countries like South Korea exemplify targeted collaboration driven by national development visions. The AfCFTA, digital transformation strategies, and Pan-African legal frameworks are extending this logic to the continental level, forming the backbone of a new African diplomacy.

Baghdad’s African turn should thus be viewed not as a favor granted to a former conflict zone, but as part of a growing pattern: African states engaging on their own terms, with partners who can bring value to their long-term goals. The road ahead must be navigated with realism. Iraq must translate its diplomatic enthusiasm into tangible initiatives. African nations must approach engagement with focus, coordination, and a sharp understanding of national interest. What emerges from this recalibration is not just a bilateral relationship, but a template for how Africa can shape its voice in a world that no longer has a single center of gravity.

In a fragmented but interconnected global order, African governments have both the opportunity and the responsibility to transform symbolic gestures into strategic outcomes. The Baghdad visit reminds us that in this new chapter of diplomacy, the initiative no longer lies solely with the old powers. It belongs to those who ask the right questions, define their own interests, and negotiate accordingly. Africa, increasingly, is doing just that.

By Tsega’ab Amare,Researcher,Horn Review