7

Apr

A Gift Unreturned: Siad Barre’s Legacy and the Fractured Narrative of Djibouti’s Birth

The story of Djibouti’s independence from France in 1977 is a fascinating chapter in the annals of African decolonization, marked by geopolitical maneuvering, regional alliances, and ultimately, a sense of betrayal. At the heart of this narrative lies the role of Somalia’s Siad Barre government, which played a pivotal yet underappreciated part in facilitating Djibouti’s transition to sovereignty.

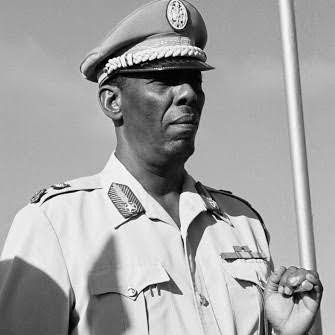

Mohamed Siad Barre, Former President of Somalia (1969-1991)

However, the relationship between Somalia and Djibouti, forged in the fires of shared anti-colonial struggle, would soon unravel, leaving a bitter legacy of mistrust and disillusionment. How the Siad Barre regime supported Djibouti’s independence, the motivations behind this support, and the subsequent betrayal that strained relations between the two nations has not been studied much.

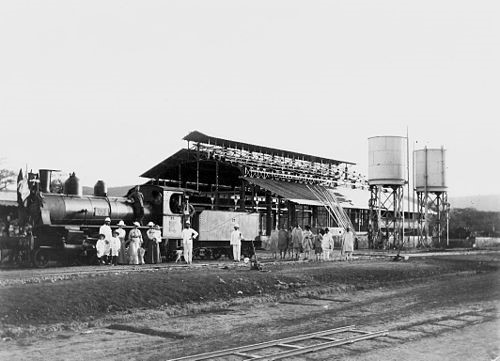

Djibouti, a small but strategically significant territory located at the mouth of the Red Sea, had been under French colonial rule upon the Fanco- since the late 19th century. Known as the land of the Afars and the Issas with strong ties to Ethiopia in its pre-colonialism, Djibouti was later referred to as the “French Somaliland” as recognised by the Franco-Ethiopian treaty of 1897, signed between Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia and the French government, primarily addressing trade, border demarcation, and railway construction.

Ethio-Djibouti Railways, 1894. Connecting Addis Ababa to then French Somaliland.

Prior to independence, Djibouti was a critical outpost for France, serving as a military base and a gateway to the Indian Ocean. However, by the mid-20th century, the winds of change sweeping across Africa had reached Djibouti’s shores. The rise of nationalist movements and the global wave of decolonization placed immense pressure on France to relinquish its hold on its last African colony.

The path to independence was fraught with internal divisions. Djibouti’s population was deeply split along ethnic lines, with the Afars, who had historically enjoyed French favor, opposing independence, and the Issas, who identified culturally and ethnically with neighbouring Somalia, advocating for it. This ethnic tension was further complicated by the broader geopolitical dynamics of the Horn of Africa, where Somalia, under the leadership of President Siad Barre, harboured irredentist ambitions to unite all Somali-speaking territories, including Djibouti, into a Greater Somalia.

Siad Barre, who came to power in Somalia in 1969 through a military coup, was a staunch advocate of pan-Somalism, an ideology that sought to unify all Somali-inhabited regions, including Djibouti, the Ogaden in Ethiopia, and the Northern Frontier District in Kenya. Barre’s government saw Djibouti’s independence as an opportunity to advance this vision. By supporting the Issa-led independence movement in Djibouti, Somalia aimed to strengthen its influence in the region and pave the way for eventual integration, and prevent Ethiopia from ever making a sovereignty claim over Djibouti.

Siad Barre’s Irredentist Claims Over Ethiopia’s Territory. Map by ACCORD. https://www.accord.org.za/publication/remembering-the-ogaden-war-45-years-later/

Somalia’s support for Djibouti’s independence was multifaceted. Politically, the Siad Barre regime lobbied extensively within the Organization of African Unity (OAU) and other international forums to pressure France into granting Djibouti its freedom. Diplomatically, Somalia provided a platform for Djiboutian nationalist leaders, such as Hassan Gouled Aptidon, to rally international support. Militarily, there were unverified claims that Somalia provided covert assistance to Issa militants, though these allegations remain contentious.

The Siad Barre government’s efforts were not entirely altruistic. By championing Djibouti’s independence, Somalia sought to weaken French influence in the region and create a buffer state against Ethiopia that could eventually align with Mogadishu’s interests. Moreover, Barre’s support for Djibouti’s independence was a calculated move to bolster his regime’s legitimacy, both domestically and internationally, by positioning Somalia as a champion of anti-colonialism and African unity.

France, facing mounting pressure from both the Djiboutian population and the international community, eventually relented. In 1977, Djibouti held a referendum in which an overwhelming majority voted for independence. On June 27, 1977, as Ethiopia dealt with internal unrests and civil wars under the Dergue regime, Djibouti officially became an independent nation, with Hassan Gouled Aptidon as its first president. The Siad Barre government celebrated this as a victory for pan-Somalism and a step closer to realizing its dream of a Greater Somalia, hence him officially declaring irredentist claims over the Ogaden and most of Eastern Ethiopian Territory leading to the Ogaden war soon after Djibouti’s independence.

Mengistu Hailemariam, Siad Barre & General Teferi Benti, 1976.

The euphoria was short-lived. Almost immediately after independence, it became clear that Djibouti had no intention of joining Somalia. Aptidon, a pragmatic leader, recognized the dangers of aligning too closely with Mogadishu, given the volatile nature of Somali politics and the potential for regional conflict. Instead, Djibouti adopted a policy of neutrality, seeking to balance its relationships with its neighbors and maintain its sovereignty.

For Siad Barre, Djibouti’s refusal to join Somalia was a profound betrayal. The Somali government had invested significant political capital in supporting Djibouti’s independence, only to see its hopes of unification dashed. This sense of betrayal was exacerbated by Djibouti’s decision to align itself with Ethiopia, Somalia’s arch-rival, during the Ogaden War (1977-1978). Djibouti’s neutrality and its subsequent cooperation with Addis Ababa were seen as a direct affront to Mogadishu’s interests.

President of Djibouti, Hassan Gouled Arriving in Addis Ababa, for Official Visit, 1981.

The fallout from this incident had lasting consequences for Somali-Djibouti relations. Siad Barre’s government, already grappling with internal instability and the fallout from the Ogaden War, viewed Djibouti’s actions as a betrayal of the pan-Somali cause. This sense of disillusionment contributed to the erosion of trust between the two nations, a rift that persists to this day.

The role of the Siad Barre government in facilitating Djibouti’s independence is a testament to the complex interplay of ideology, strategy, and self-interest in international relations. While Somalia’s support was instrumental in Djibouti’s journey to sovereignty, the divergent paths taken by the two nations in the aftermath of independence underscore the limitations of pan-Somalism as a unifying force. For Djibouti, independence was not a stepping stone to Greater Somalia but a means of asserting its own identity and sovereignty. For Somalia, the experience was a painful reminder of the challenges of realizing its irredentist ambitions.

The story of Djibouti’s independence and the subsequent “betrayal” of Somalia’s expectations is a microcosm of the broader struggles faced by post-colonial African states. It highlights the tensions between regional solidarity and national interests, the challenges of navigating complex geopolitical landscapes, and the enduring legacy of mistrust that can arise from unmet expectations. As Djibouti continues to thrive as a strategic hub in the Horn of Africa – with stronger ties to Ethiopia, and Somalia grapples with its own challenges, the lessons of this chapter in their shared history remain as relevant as ever.

By Horn Review Editorial